"Million Dollar Baby" author left behind a

novel of caring and fighting in the boxing world

The man who wrote "Million Dollar Baby" died in 2002, before his story hit the big screen

and won Oscars and a global audience. Still, by all accounts he was satisfied.

He'd written for decades with no response but rejection slips. Then a literary magazine

published one of his stories. An agent read it and asked if he had more. He did and the

result was published in 2000 as "Rope Burns," the acclaimed volume of boxing stories that

includes "Million Dollar Baby."

He wrote under the name F.X. Toole, a moniker

fabricated, he said, in salute to the missionary saint Francis Xavier and Irish actor

Peter O'Toole. He was known in the boxing world as Jerry Boyd, a respected cut man and

trainer in Los Angeles fight gyms for many years. Though his writing is set in the world

of boxing, he kept it secret there until he was finally published.

When he died at

the age of 72, F.X. Toole left behind the thick manuscript of a novel, "Pound for Pound."

Edited by his agent and a freelance editor, the novel appears with an introduction by

fight fan and noir stylist James Ellroy. It carries the Toole stamp of lean,

conversational storytelling and dialogue rich in an American polyglot of tic and rhythm.

"Pound for Pound" occupies the same bruising terrain as Toole's short stories. The

primary actors are fight guys -- boxers and trainers. There is plenty of pugilistic lore,

but boxing is the setting, not the subject. For Toole the sport is a laboratory where

human fiber is tested, dissected and displayed under crisis conditions.

The novel

crystallizes Toole's deeply moral view of existence. His bad guys are one-dimensional,

relentless and unforgivable. Evil is almost religiously defined as the absence of light.

But "Good" is complicated and hard. His characters stumble, grope and struggle for it.

When it happens it is a mystery and a blessing achieved through the oldest of verities --

love, loyalty and commitment.

"Pound for Pound" centers on Dan Cooley, an aging

ex-boxer turned trainer. His auto repair shop in Los Angeles has a boxing gym out back.

The stoic Cooley has endured harsh losses, including the deaths of his wife and children.

But as the story opens he is a decent man maintaining his equilibrium with the clear

purpose of teaching and caring for his small grandson.

When the child is killed in

a traffic accident, Cooley loses it. All the contained pain of his life explodes in fury.

He dives into the bottle and plots a terrible revenge against the driver who did the deed.

Then he turns the rage against himself and the God he believes in and hates. He

methodically prepares for a gruesome suicide that will obliterate any trace of his

existence.

Meanwhile, far off in San Antonio, an old ring rival of Cooley's is

also a grandfather. But this rival, Eloy "The Wolf" Garza, is dying and the vultures

surrounding the sport are eager to strip all the hope and talent out of his grandson, a

gifted boxer. As a last, desperate attempt to save his grandson's dreams, The Wolf sends

him to Los Angeles to ask Cooley to train him for a professional career.

Predictably, the living grandfather steps up for the dead. Someone else's grandson

stands in for the lost child. But nothing comes easy for Toole's characters. There are

twists at every step. If goodness is to triumph it must out-connive evil. The savagery of

"Pound for Pound" is inextricably melded with profound sweetness. That's how F.X. Toole

saw the world.

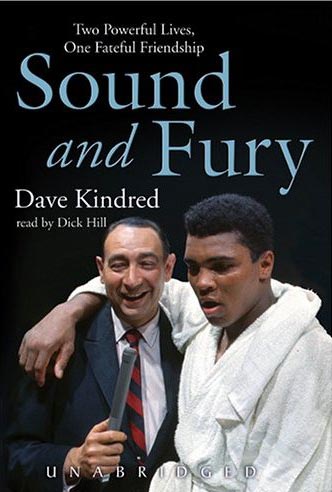

Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell: Hand

in Glove

Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell: Hand

in Glove

Okay, I did not jump for joy at the news of yet another

addition to the mountain of books -- some excellent, many

silly -- about Muhammad Ali. And admittedly, hearing that

veteran sports reporter Dave Kindred's "Sound and

Fury: Two Powerful Lives, One Fateful Friendship" pairs

the great boxer with the late, grating sportscaster Howard

Cosell, I sneered. Yes, I am one of what Kindred calls

"the mean-spirited punks" who dismissed Cosell as

a pompous twit. It's not the first time I've been

wrong in several directions at once.

Kindred's perceptive book offers a deeper view.

"Sound and Fury" is a charmer with three good

stories -- the separate lives of Ali and Cosell, and the

tale of their scriptless collaboration to create media

storms.

Kindred's research is solid, but he also knew and liked

both men. His personal anecdotes and interpretations are

fresh and zesty. The book begins with a description of

Kindred literally crawling into bed with Ali to get an

interview in a noisy Las Vegas hotel suite crowded by

"the Ali Circus madhouse of perfumed women,

pimp-dressed hangers-on, sycophants, con artists,

sportswriters, and other reprobates." Of Ali, Kindred

writes, "I saw him naked. I am not sure I ever saw him

clearly."

The sportscaster appears as Kindred is sitting at the

breakfast table in Cosell's beach house. "I saw in

the shadows across the room a ghostly shape that on

inspection turned out to be my host shuffling barefoot from

his bedroom, skeletal in a white undershirt and boxer

briefs. He was bleary-eyed. He had not yet found his toupee.

As Cosell noticed me, he raised his arms and struck a

bodybuilder's biceps-flexing pose. Then he spoke, and

this is what he said: 'A killing machine the likes of

which few men have ever seen.' "

Cosell laughing at himself wasn't Kindred's only

surprise for me. "Sound and Fury" snatches both

men out from behind the flimsy cartoons that often represent

them. Cosell was more than an arrogant poser. Ali is neither

Superman nor saint. Kindred's entertaining

prestidigitation reveals dynamic egos, remarkable gifts and

plenty of warts.

Turns out the unlikely duo had a lot in common. The handsome

young African American Muslim boxer from Louisville and the

homely older white Jewish lawyer from New York were both

bedeviled by stereotype and racism. TV demanded bland

accents, faces and vocabularies. But Cosell powered his

polysyllabic Brooklyn rasp and his non-Ken-Doll mug to the

hugely successful sportscasting career that allowed him to

escape the law practice he hated. The white America that

adored polite Joe Louis and gentle Floyd Patterson was not

ready to stomach the Louisville Lip, much less the radical

separatism of Ali's conversion to the Nation of Islam.

Both men were driven by fear. Cosell had a horror of failure

and disrespect. The deeply religious Ali was awed by the

physical threat of the murderous Elijah Muhammad, then

leader of the Nation of Islam. Kindred argues persuasively

that the politically naive Ali's abandonment of his

mentor, Malcolm X, and his refusal to be drafted into the

U.S. military were in obedience to Elijah Muhammad.

Ali's willingness to appear on any show with Cosell was

an asset for the broadcaster. Cosell -- who had changed his

name from Cohen -- was the first to publicly agree to call

Cassius Clay by his new Muslim name. Cosell defended

Ali's right to refuse induction and attacked the New

York commission that stripped Ali of his license to box,

leaving the fighter unemployed and scrabbling for years at

the height of his athletic powers.

Kindred takes them from their disparate beginnings through

triumphs and hard times, and follows them into their

parallel decline in the 1980s. Cosell's feuds and rants

finally got him booted off television entirely. He lost

heart and health when his beloved wife died.

When Elijah Muhammad died, Ali embraced a milder form of

Islam, and the old aggravations evaporated from the public

consciousness. Not forgiven, but forgotten. Muted by the

Parkinson's disease that is probably the result of the

beatings he took late in his career, the depressed Ali

drifted into deliberate obscurity. When he emerged to light

the torch at the 1996 Olympics his global fame rekindled. To

get past grousers like me, Cosell's revival needed Dave

Kindred.

The boxing match that

broke America's color line in sports

The boxing match that

broke America's color line in sports

In 1910, Jack Johnson shattered the color line that barred

black athletes from competing with whites. His punishment

for that defiance combined with his vivid, innovative talent

to make him a haunting figure in American sports.

Many of today's fight fans first learned about the

great black champion from Muhammad Ali, who hailed Johnson

as a hero and role model. In 2005, an remarkable two-part

documentary by Ken Burns, "Unforgiveable Blackness: The

Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson," was broadcast twice on

PBS. The filmmaker launched a substantial movement including

political and labor leaders, as well as boxers, petitioning

President Bush to pardon Johnson from his federal conviction

under the Mann Act.

Every substantial history of boxing in America pays respects

to Johnson, and to the bizarre extravaganza that surrounded

his smashing of the original Great White Hope, Jim Jeffries,

in their July 4, 1910, bout. Still, as Wayne Rozen notes in

his introduction to "America on the Ropes: A Pictorial

History of the Johnson-Jeffries Fight," until now there

has not been a book solely about this match, which defined

Johnson and threw a harsh, clear light on the racial

conflict in the United States half a century after the Civil

War.

Rozen's book is a gorgeous monster in size and content.

It is packed with amazing photographs, posters, cartoons,

clippings and other ephemera that help bring the men and the

era to life. Rozen's entertaining prose paints dynamic

and cranky personalities and the hurtling momentum of their

times. Though it is carefully researched and documented,

"America on the Ropes" reads like adventure. We

may already know the plot, but Rozen dishes up so much

engaging detail, so many obscure or raucous anecdotes, and

such a strong day-by-day progression toward the climax that

we live the nervy suspense as the big fight approaches.

As Rozen writes, "America was the land of opportunity,

a land where every man had his own shot at fame and fortune

. . . Unless, of course, he was black . . . Between 1901 and

1910, 754 blacks were lynched in the United States . . . In

1910 the social and political rights of blacks were less

secure than at any time since slavery."

In this volatile context, Rozen sketches the lives of

Johnson and Jeffries, and of the dashing promoter, Tex

Rickard, who orchestrated the historic clash. The story

gathers steam as the heavyweight champion, Jeffries,

retires, having enforced the color bar and refused to allow

any black fighter to challenge for the title. When Canadian

Tommy Burns took the championship, Johnson chased him to

Europe -- enduring humiliations remarkable even for that era

-- and then to Australia.

Burns had defended the title twice in Australia, but on Dec.

26, 1908, Johnson toyed with the out-classed Burns. The most

significant character watching in the huge crowd was Jack

London. Stopping off in Australia on his way home from

covering the Russo-Japanese War for American newspapers,

London reported the fight for the New York Herald. London

was as racist as most people in those days, and his

description of the white champion's humiliation at the

hands of Johnson blanketed North America in a matter of

days. The crucial paragraph was London's final plea for

Jeffries to come out of retirement and "remove that

smile from Johnson's face."

This inflammatory article and the press that followed

powered the storm that drove Jeffries and the nation to the

events in Reno on July 4, 1910.

Rozen's wonderful description of the Johnson-Jeffries

bout itself is illustrated by an impressive series of

round-by-round photographs of the ring action. The aftermath

is swiftly dealt with, but the author sketches each of the

fighters lives to their end. The book concludes with the

popular Mutt and Jeff cartoon strips that ran on the funny

pages of the nation's daily papers. The gritty ink

comedians play out their shady triumphs and absurd

catastrophes on the way to and from the big fight -- a wry

mirror for a grand, if grotesque, folly.

Katherine Dunn is associate editor of the Cyber Boxing Zone. She can be reached

at kkdunn0@yahoo.com.

All three reviews first appeared in the Sunday Oregonian on August 27, 2006.