|

Vince Martinez, One of Boxing's Forgotten

Warriors

By Dan Cuoco

There are many

stories of past greats and famous boxers that have been written and rewritten

over the years. But what about the many who fought and made a name for

themselves but seem to be forgotten as the years pass by. Vince Martinez is one

of them.

Vince was born

in Mt. Kisko, New York to Anthony (Tony) and Paulina Martinez on May 5, 1929. He

was the second of four boys: Phillip, the eldest, Vince, then Charles and John.

Despite his Spanish surname, Vince is Italian and very proud of his ancestry.

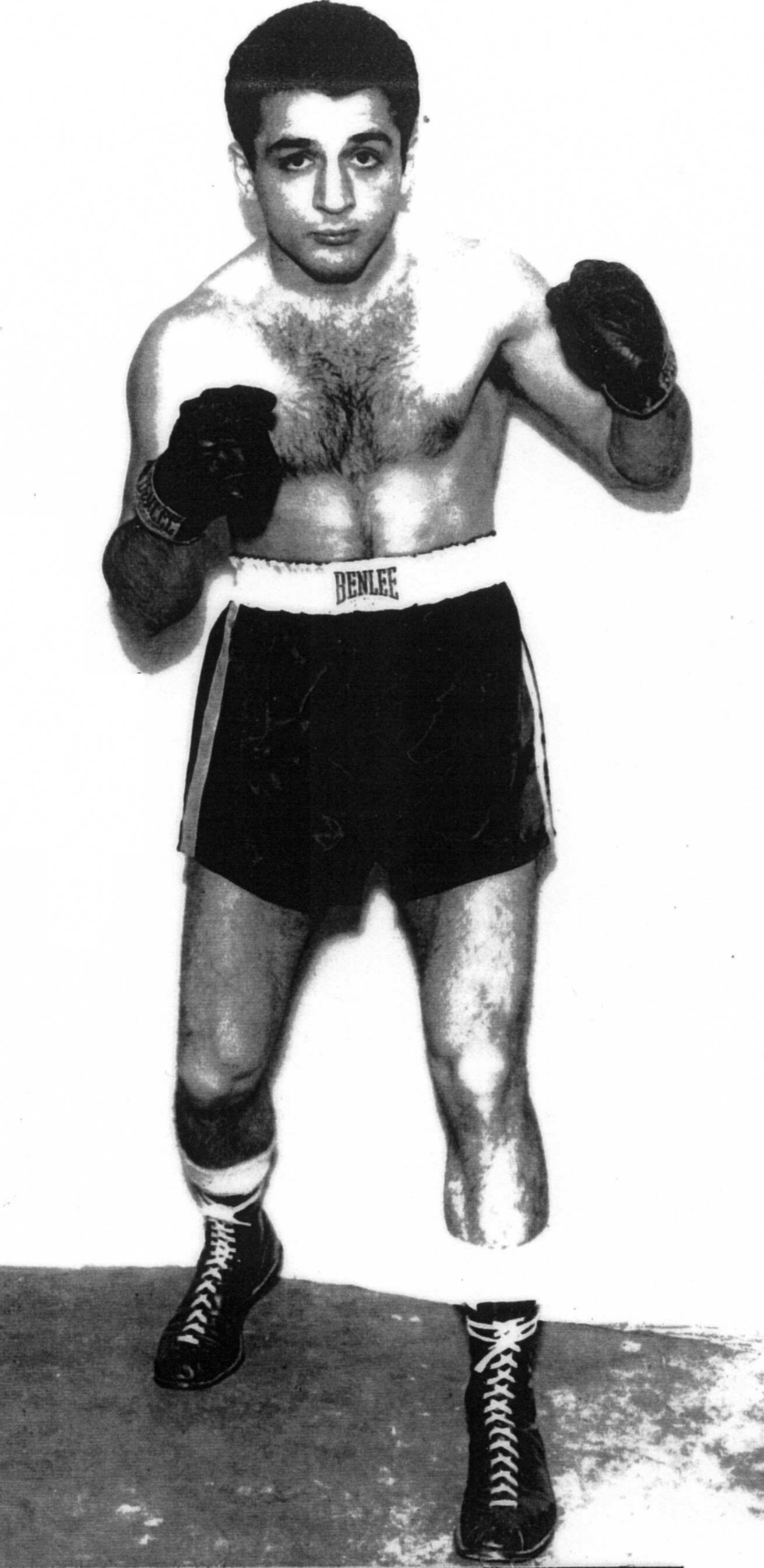

Martinez was a sharp shooting boxer with a devastating left hook, a hard right

hand and one of the best counter punchers in the ring. He was fleet of foot, a

cautious boxer, but would go all out to finish an opponent once he hurt him.

Vince's

thoughts on his style are best summed up when he stated to a reporter, "If you

identify yourself as a professional boxer in any crowd merely by the evidence of

punishment you have taken, you can't be too good." That philosophy, however,

occasionally caused some fans to be turned off by some of his performances when

they thought that a more aggressive posture would have produced more spectacular

knockouts.

Vince was a

fall back to earlier times when boxing idols had large local followings that

traveled anywhere to see them perform. He was also considered the idol of the

1950's bobby soxers because of his movie star good looks. He was one of boxing's

most photogenic fighters and received Hollywood offers.

At the age of

four Vince’s family moved to Peterson, New Jersey where he was to grow up. At

Central High School in Paterson Vince played football. In his senior year, the

entire football team decided to enter the 1947 Paterson Diamond Belt Gloves.

Vince followed suit and surprised everyone by making it all the way to the

finals.

Bitten by the

boxing bug, Vince joined the Mickey Connelly Gym in Paterson and started to

learn his newly chosen trade. He was initially taught boxing fundamentals by his

father Tony. He fought in the Paterson amateur club circuit for experience

through the balance of 1947.

Vince worked

hard at his new craft and proved to be a natural. In 1948 Vince entered and won

both the Paterson and Passaic, New Jersey Diamond Gloves.

In 1949 he

decided to turn professional under the management of Tex Pelte, Bill Daly and

his father, with Nick Fiorita who trained him in the amateurs as his trainer.

He made his professional debut on March 9, 1949 with a four round decision over

Joe Lucarelli in Jersey City.

Vince went

undefeated in his first 14 professional fights (5 by kayo) before losing a six

round decision to Joe Mullins in New York on February 28, 1950.

After the

Mullins fight, Vince was out of the ring for six months as a member of the New

Jersey National Guard. He returned to the ring on October 10, 1950 with a fifth

round knockout victory over Jack Rudolph in New York.

Vince was a

much harder puncher than his early record indicated. And he proved it upon his

return from National Guard duty by stopping 10 of his next 14 opponents to run

his professional record to an impressive 27-1, with 15 kayos before dropping

back to back ten round decisions in New York to Chico Vejar and Danny Giovanelli.

Among his 27 victims were knockouts over tough and tested veterans Larry Gassa,

Eddie Holtz, Red DeFazio, Dick Cannady, Carey Mace, Mario Moreno, Sal DiMartino,

Tony Pellone and Don Williams; and decisions over Sam Giuliani and Carmine

Fiore.

Vince made his

first big-time start when he headlined an eight round main event at St. Nicholas

Arena, New York on January 28, 1952 against Mario Moreno. His record at the time

was 21-1-0 (11). The veteran Moreno had 71 professional fights and his opponents

included Vic Cardell, Joe Miceli, Tony Janiro, Lew Jenkins, Ross Virgo, Johnny

Saxton, Chester Rico, Ernie Durando, Bobby Dykes and Joey Giambra. Moreno gave

Vince trouble through the first four rounds, but Vince eventually figured him

out and dropped him twice in the sixth round with a blistering two-fisted

assault causing referee George Walsh to intervene and award Vince a sixth round

technical knockout.

Vince followed

this victory with a devastating sixth round knockout of Hartford, CT veteran Sal

DiMartino at St. Nick's Arena. Vince boxed smoothly from long range for the

first five rounds before suddenly exploding in the sixth round. A flurry of

rights and lefts sent DiMartino flat on his back for the first knockdown, and

when he stumbled up, another barrage dropped him flat on his face. Realizing it

was a waste of time to start a count referee George Walsh wisely called a halt

to the fight.

In his next

fight Vince scored the biggest win of his early career with one-round blowout of

former high ranking contender Tony Pellone in his national TV debut. Vince,

normally a slow starter, liked to fight at long range content on using his jab

to keep his opponent off balance while waiting to unload his hard right hand.

But Vince surprised everyone including Pellone by unleashing a blistering

two-handed assault at the opening bell. Pellone tried desperately to keep Vince

off of him but he couldn’t compete with Vince’s speed and deadly accurate

punches and was dropped three times before the referee stopped the fight at 2:54

of the first round.

Martinez

closed out 1952 with victories over Sammy Giuliani (W-10), and Don Williams

(TKO-9) finishing the year at 5-0 (4 KOs) earning him the Boxing Writers

Association's prestigious "Rookie of the Year Award" for 1952.

Vince began

1953 with a ten round decision over tough Carmine Fiore to run his unbeaten

streak to 13 (overall record 27-1-0 (15)) before losing two close back-to-back

decisions to Chico Vejar and Danny Giovanelli.

Jersey Jones'

May 1953 Ring Magazine coverage of the Martinez-Vejar fight was colorful to say

the least.1

"A series of 13's may have proved unlucky for Vince

Martinez but they were a happy combination for Chico Vejar and Madison Square

Garden. Vejar won the decision in a bristling ten-rounder, before the biggest

crowd (11,184) and the largest gate receipts ($45,770) drawn by a Garden fight

in a year and a half.

The bout between two popular youngsters, not only had an

exceptional appeal to the public, but also brought out big personal followings

of the rivals. It was estimated that three-fourths of the house was represented

by Martinez's enthusiastic cohorts from New Jersey and Vejar's loyal crowd from

Connecticut.

Martinez, with 13 letters in his name, boasting a winning

streak of 13 straight, and fighting on Friday the 13th (of March),

was a top-heavy favorite in advance speculation. Prices ranged from 17-5 at

weighing-in to 4-1 at ringtime. But the Patersonian's superior boxing skills and

sharper punching weren't enough to offset the aggressiveness and determination

of the plucky Vejar. Chico crowded his opponent all the way, absorbed his

heftiest clouts, and came on to outlast him in a battle that teemed with action.

Vejar actually won the fight when he survived a stormy seventh round. In that

session Martinez cut loose with everything he had for two minutes and Chico was

in serious trouble. But the gritty 21-year old Nutmeg Stater staged a strong

comeback in the final minute and a lusty left hook to the body had Martinez in

distress in his own corner at the bell.

The 23-year-old Patersonian faded from then on. Vejar

also was tired but refused to admit it. Doggedly, he continued to force the

action, scored with lefts to the face and hurt Martinez several times with

rights to the body.

An unusual development was the voting of the officials.

All three scorecards of Referee Al Berl and Judges Charley Shortell and Harold

Barnes declared victory for Vejar by identical 5-4-1 counts.

It was Vejar's 59th triumph in 62 bouts and

his eighth straight since his losing series with Chuck Davey in Chicago and

Detroit. "

Martinez and

Vejar were scheduled to fight again at Madison Square Garden in May but Vejar

was forced to pull out when he was inducted into the U.S. Army. The matchmakers

substituted Vejar with one of their up and coming developments Danny Giovanelli.

Giovanelli, with a record of 19-2-0 (9), was a busy, colorful youngster, with a

real zest for fighting. His main attribute was his two-fisted non-stop style

which didn't allow his opponents much chance to rest. Giovanelli waged a

relentless fight. He set a blistering pace from the start, swarming all over

Martinez, backing him into the ropes and into corners. Vince was forced to fight

back in self defense. The action was sustained and the Garden crowd was on its

feet for most of the fight. Martinez hurt Giovanelli several times with jolting

left hooks and hard right hands, but Giovanelli was able to shake off the

effects and come back with a blistering attack of his own. Giovanelli was

staggered badly in the sixth and sent to the canvas for an eight count in the

ninth from a hard right cross. But a tired Giovanelli had enough left to

outfight Martinez in a torrid tenth round to walk away with a close decision.

After his

losses to Vejar and Giovanelli, Martinez began to work harder on his

conditioning to avoid fading again in the late rounds as he had done in the

Vejar and Giovanelli fights.

The hard work paid off as Vince went

undefeated in his next 23 fights (10 kayos) starting with a sixth round knockout

over Billy Andy in Newark on August 20, 1953 and ending when he lost a close

decision to former welterweight champion Tony DeMarco in Boston on June 16,

1956. During that stretch his most prominent victories were over Chico Vejar in

a return match (W-10), Rocky Casillo (KO-3), Harold Jones (W-10), Chuck Davey

(TKO-7), Art Aragon (W-10), Al Andrews (W-10), Chico Varona (W-10), Bob Provizzi

(W-10), Lester Felton (W-10), Mario Terry (KO-3), Chris Christensen (W-10),

Peter Muller (KO-2), Paolo Melis (W-10), Miguel Diaz (W-10) and Dick Goldstein

(W-10). starting with a sixth round knockout

over Billy Andy in Newark on August 20, 1953 and ending when he lost a close

decision to former welterweight champion Tony DeMarco in Boston on June 16,

1956. During that stretch his most prominent victories were over Chico Vejar in

a return match (W-10), Rocky Casillo (KO-3), Harold Jones (W-10), Chuck Davey

(TKO-7), Art Aragon (W-10), Al Andrews (W-10), Chico Varona (W-10), Bob Provizzi

(W-10), Lester Felton (W-10), Mario Terry (KO-3), Chris Christensen (W-10),

Peter Muller (KO-2), Paolo Melis (W-10), Miguel Diaz (W-10) and Dick Goldstein

(W-10).

His return

bout with Chico Vejar was most satisfying. Here is Jersey Jones' ringside

report.2

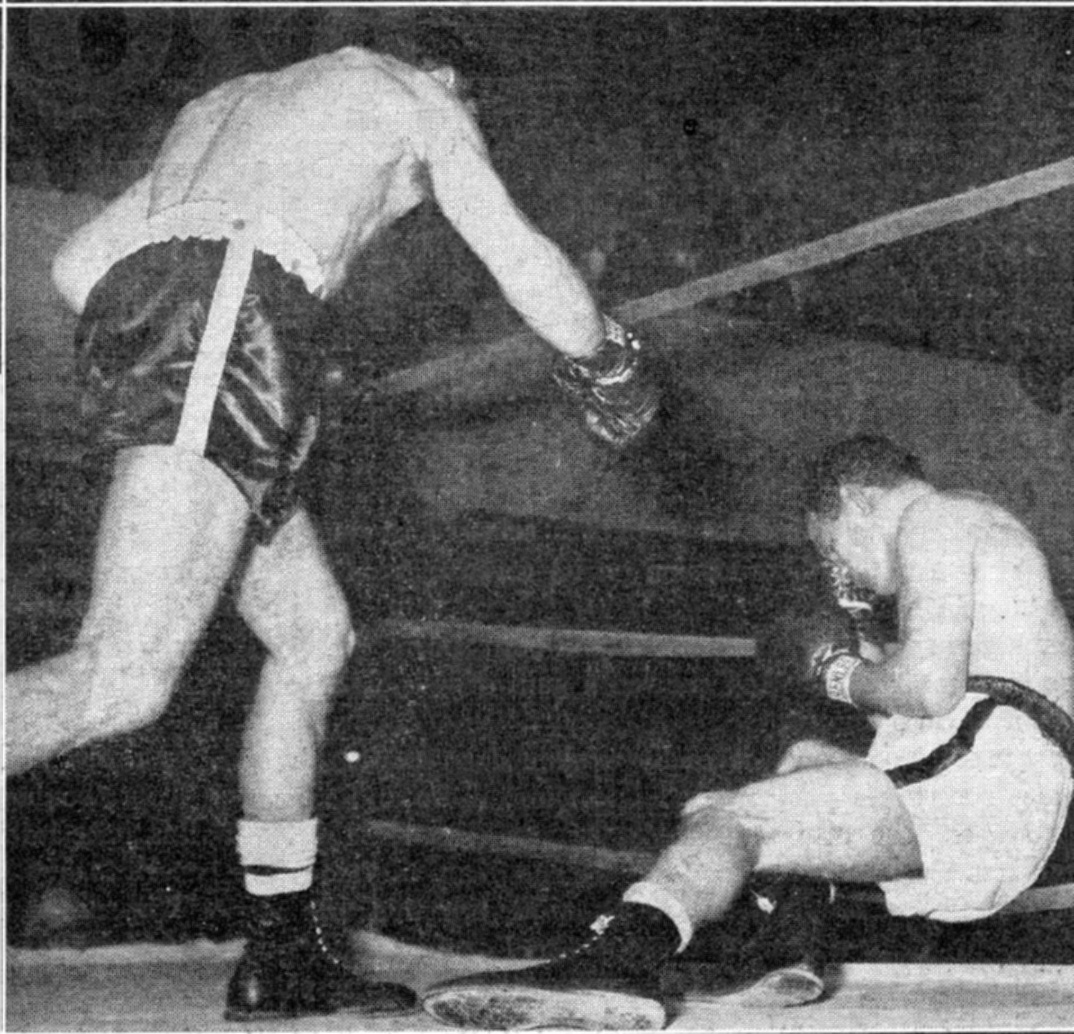

“Badly battered in the first, and dropped to one knee in the second, Chico

Vejar, 149 1/2. Stamford, CT., staged a plucky comeback but couldn't quite catch

Vince Martinez, 150 1/2, Paterson, in an action packed ten in Madison Square

Garden. By winning, Martinez evened the score for the licking Vejar tossed into

him in the same ring eight months before. On leave from his Army post at Fort

Benning, GA., Chico was off in timing and stamina, but didn't stop trying.

Recovering from Martinez's early blasts, Vejar crowded Vince the rest of the

way, but did a lot of missing and floundering in his attempts to catch the

fleet, back-pealing, counter-punching Patersonian. Tiring from the furious pace,

Chico suddenly shifted to southpaw tactics in the sixth, but they proved

ineffectual and he changed back to his normal style. Vejar continued to fight

doggedly, and had the score almost even going into the last round, but he didn't

have enough left for the final drive, and Martinez closed fast enough to clinch

the verdict. The large personal followings of the rivals accounted for a fine

turnout of 7,317 and a gross gate of $27,267.”

Although Chico

was still in the Army, he was in fighting shape having engaged in two fights

before meeting Vince on November 20, 1953; ten round decisions over Chico

Pacheco in Miami Beach, FL. on October 13, 1953 and Ronnie Harper in Ft.

Lauderdale, FL on November 10, 1953.

Vince began

1954 by facing Blue Island. IL's Rocky Casillo on January 24th in New

York. Casillo, possessing a record of 20-3-0 (10) was just coming off the

biggest victory of his career a tenth round stoppage of Danny Giovanelli. He

also had kayoed seven of his last eleven opponents. New York Times reporter

Joseph C. Nichols covered the fight.3

Vince Martinez erased Rocky Casillo from the big league

boxing picture last night. In the three full rounds that went on the fans saw

nothing that resembled a contest. Casillo had nothing to offer the classy

Martinez who scored four knockdowns in the short time that the scheduled ten

rounder lasted.

Because Casillo had beaten Danny Giovanelli in a previous

New York appearance, Martinez was cautious in the first round. He had reason to

be, for he had lost to Giovanelli in a ten-rounder last year.

After testing the Westerner for the opening three

minutes, though, Vince found that Casillo 'didn't have a thing.' He went to

work on his foe in the second round, stepping around him speedily, sticking

repeatedly with lefts to the head and crossing sharp rights to the jaw.

One of these sequences dropped Casillo pretty heavily,

but Rocky got to his feet at 7 and took the automatic 8 count. Near the end of

the session Vince let fly with a long right to the jaw. Down went Rocky again.

He was up quickly, but took the automatic 8.

Martinez let Casillo have everything in the third. The

latter tried to land a right to the head, but Vince easily drew away and floored

Rocky for an automatic 8 count.

At the conclusion of the third round, Dr Vincent

Nardiello examined Casillo and gave Referee Rudy Goldstein the nod to end it."

Vince followed

this win with victories over Joey Bishop in Akron, OH (W-10), Ronnie Harper in

Boston (KO-2) and Harold Jones in Youngstown, OH (W-10) before heading to

Chicago on May 26, 1954 to meet former welterweight title challenger Chuck Davey

(40-4-2 (26). The New York Times coverage of the fight follows.4

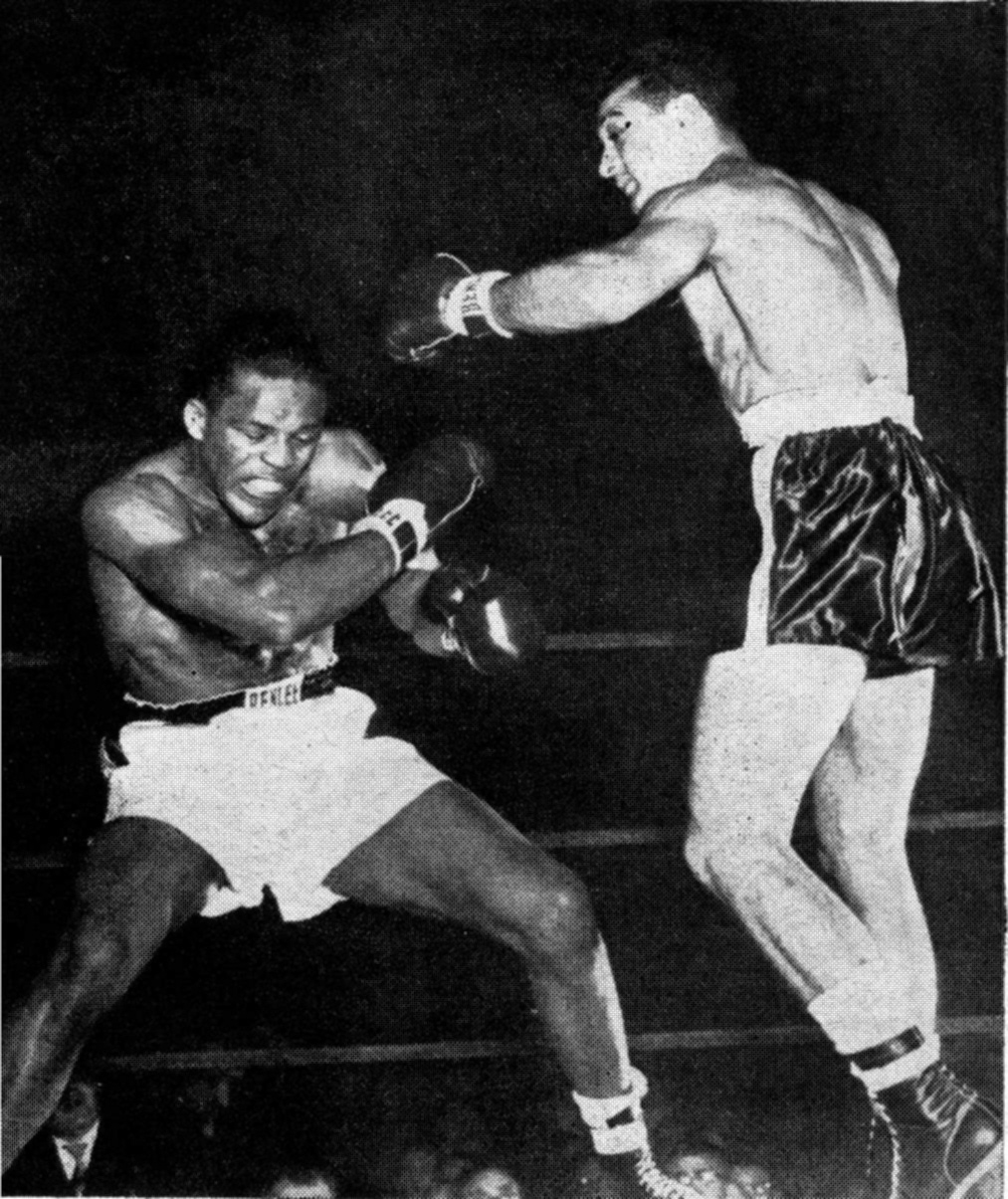

"Vince Martinez, 148 1/2, pounded Chuck Davey, 149, into

complete submission tonight, for a seventh-round technical knockout in the

Chicago Stadium.

Davey never was in contention. He was down four times

before failing to come out for the seventh and he was close to a knockdown on

two other occasions.

Martinez set the pattern of the battle in the first

round. Davey, boxing well, apparently was in command. But, Martinez, who now has

won his last ten bouts, six by knockout, slipped through a right hook that sent

Davey to the canvas

He was up at 4, but his confidence was gone. Martinez

took the second round with cagey in-fighting and in the third Davey went down in

the opening minute.

He was hardly on his feet, before Martinez closed in

again, and with a right, a left, and a right, put the former Michigan State

fighter down for eight. Davey rallied, but another left from Martinez staggered

him at the bell.

It was almost an even fight then for two rounds as Davey

moved quickly and beat Martinez to the punch on occasion to pick up a few

points. Davey, though, went to the wrong corner after the fifth.

In the sixth Martinez closed quickly and, with three hard

rights, he dropped Davey for the fourth time.

Davey arose then, but he was obviously groggy. As the

round ended, Davey clutched at the ropes in a corner from a heavy barrage by

Martinez. Dr. Irving Slott went to Davey's corner and signaled the finish."

Next up for

Vince was a meeting with number eight-ranked welterweight contender Art (Golden

Boy) Aragon in Los Angeles on July 1, 1954. Aragon's record was 61-14-5 (41).

Boxing

Historian Matt Tegan states in Art's CyberBoxingZone biography,

"Art Aragon was boxing's "Golden Boy" prior to Oscar De

La Hoya (though Twenties heavyweight Jack Demave was the first to use the

nickname.) Aragon was a colorful and extremely popular contender in both the

Lightweight and Welterweight divisions, based out of Los Angeles during the

1950's. Aragon beat such good fighters as: Enrique Bolanos, Teddy "Redtop"

Davis, Johnny Gonsalves, Jimmy Carter, Lauro Salas, Don Jordan, Danny Giovanelli,

and Chico Vejar.

In his sole title shot, Aragon was completely dominated

by Jimmy Carter, whom he previously had defeated. The mob-controlled Carter was

known to be "Carbonized", meaning that he often fought on orders from Frankie

Carbo. He would usually fight poorly when the odds were heavily in his favor, as

they were in his non-title fight with Aragon."

Ring

Magazine Correspondent Bill Miller was at ringside for the Martinez-Aragon fight

and turned in this report.5

"A crowd of 17,158 cash customers paid a nice sum of

$130,262 to see Vince Martinez, 146, the Paterson Pulverizer, score a unanimous

10-round duke over Art Aragon, 145 ½, the Golden Boy at Hollywood Ball Park.

It could not be considered an upset, for Martinez ruled

10-6 favorite at ring-time. Nevertheless the experts had been fairly evenly

divided in their prophecy of the

outcome. Many picked Aragon to win by a knockout.

Yes, Aragon lost some of his glit-but he got a healthy

wad of gelt to console him for the loss of that glitter. Both boys received

purses of $27,500, which is a very exclusive and desirable neighborhood when you

take into consideration that Aragon was rated No. 8 among the world’s welters,

and Martinez not even included among the top ten.

Undoubtedly, they’d have drawn an additional $20,000 had

there been parking-space available; thousands of customers drove away in disgust

when they were unable to find a place to park their cars.

Now, as for the fight itself. It was a humdinger. There

was enough gore to satiate the most blood-thirsty fan; there was action from

start to finish, and plenty of thrills along the way.

Here is the official scoring: Referee Abe Roth, 59-51;

Judge Frankie Van, 59-51; and Judge Reg Gilmore, 60-50.

I said it was a social success; well, the wit, brains and

beauty of the film industry was on hand. At ringside were Jack Dempsey, Mickey

Walker and their famed manager Jack Kearns; Henry Armstrong; Jimmy McLarnin;

Barney Ross; the great old-timer Joe Rivers; popular Enrique Bolanos, and many

lesser lights.

Martinez turned in a smart, brainy performance and

established himself solidly here."

Martinez's

impressive win over Aragon forced Art out of the ratings and Vince replaced him

in the eighth position.

Vince extended

his winning streak to eleven on July 1, 1954 in New York in a rematch with tough

Brooklyn welterweight Carmine Fiore, 47-16-5 (18) The New York Times Frank M.

Blunk covered the fight.6

"Vince Martinez, the sharp-punching welterweight from

Paterson, who is fighting his way to a championship bout, stopped Carmine Fiore

of Brooklyn in the seventh round of their scheduled ten-round contest in Madison

Square Garden last night.

The end came after 2 minutes 32 seconds of the round.

Fiore was helpless on the ropes when Referee Harry Kessler called a halt. The

loser was cut over both eyes and another good punch would have finished him.

A terrific right cross to the chin, landed by Martinez as

Fiore retreated into a corner, was the blow that started Fiore on the way to

defeat. That punch made Fiore's knees buckle and he tried to cover against the

barrage of lefts and rights that followed. But he was too dazed to block all the

punches.

A straight right cut Fiore's brow. Two slashing lefts and

the right brow was opened. Now Fiore was both dazed and blinded. He fought his

way out of the corner and that was courageous, but not the best thing to do. For

as he moved into the center of the ring he was wide open. All his defenses were

gone. A left hook to the jaw, a right to the chin and he fell into the ropes,

all done.

Fiore is one of the hardest hitters in the welterweight

division, especially with his left. He is a forcing, aggressive fighter, but he

is no boxer. Martinez is a superior boxer. He fights in the classic style and

when he lands a punch it is sharply landed, and it jars and hurts.

From the beginning until that first right landed in the

seventh, Martinez was the master. He met the bull-like rushes of Fiore as deftly

and as gracefully as a matador, side-stepping and punching, moving in for the

jab.

When the seventh started Fiore's attack was furious and

it was desperate. But Martinez could not be drawn into that sort of fighting. He

jabbed and he jabbed and then the right, and that was all of it.”

Vince closed out 1954 on

December 10th with a unanimous decision over Al Andrews in New York.

He was third ranking welterweight in The Ring World Ratings behind number one

ranked Carmen Basilio and number two ranked Kid Gavilan. The champion was Johnny

Saxton.

Shortly after the Andrews

fight Vince did not renew his contract with managers Bill Daly and Tex Pelte

because he was being short-changed financially. It all started with Vince

innocently asked where all his money was going. When he wasn’t happy with the

answer he decided not to renew his contract. Little did he know at that time

that he would not enter the ring again until June 1955.

Vince showed

tremendous courage in splitting with Daly and Peltre. Daly was general treasurer

of the powerful International Boxing Guild and Peltre was Daly's managerial

associate. Because the International Boxing Guild was so strong, no one in the

New York area would let Vince fight for them despite his high ranking.

Consequently, Vince was forced to bring charges before the New York State

Athletic Commission (NYSAC), headed by one time racket-buster Julius Helfand,

that he was being boycotted. He stated in his charge that he has been

unable to sign for a bout since last December, when he broke from his managers.

The NYSAC held a series of hearings resulting in the suspensions of Bill Daly

and Tex Peltre for acts detrimental to boxing.

In the end

Helfand outlawed the Boxing Guild of New York, the strongest branch of

International Boxing Guild. He had a solid case. He termed the guild’s

activities as “vague and shadowy,” its witnesses as displaying “a startling and

abysmal ignorance, its records as “careless and haphazard,” its boycott of

uncooperative fighters as “vicious,” and its practices as “underhanded and

dishonest.” And his most striking example was the case of Vince Martinez. He

stated “when Martinez refused to renew his contract with Daly, one of the most

powerful figures in the guild, and tried to manage himself, a boycott was

clamped on him. He couldn’t get a fight anywhere. Since he rehired Daly,

however, he’s been working his trade.”

Vince finally

returned to action on June 24, 1955 in Syracuse, NY winning a 10 round decision

over Chico Varona, 68-20-3 (41). While on hiatus he had dropped one spot in the

rankings because of inactivity – he was now the fourth ranking welterweight in

the world. Ahead of him were Tony DeMarco (#1), Johnny Saxton (# 2) and Ramon

Fuentes (# 3). Carmen Basilio was champion. The Associated Press coverage of the

fight proved that Vince was still in top form.7

“Vince Martinez, 151 ½, of Paterson, NJ brought his

hit-and-run style back to the ring tonight and scored a unanimous decision over

a puzzled Chico Varona of Cuba, 155.

Martinez proved convincingly that a six-month layoff

hadn’t hurt him. He used his left jab tantalizingly throughout and stood

toe-to-toe with the heavier, stronger Varona when several occasions demanded it.

The bout’s finish brought the crowd of 1,701 to its feet.

The fighters handed each other vicious punishment for the last two minutes.

Judge Ted Shells scored it 8-1-1. Judge Dick Fazio had it 7-2-1 and Referee Mark

Conn called it 7-3-0. The AP had it 7-3-0.

Martinez knocked Varona down with a quick left-right

combination to the chin just before the bell ending the fourth round.

Martinez seemed in superb condition. For the early rounds

he was content to jab away with his speedy left and whirl away from his opponent

before the Cuban could get in a blow.

In the fifth round Varona tried to carry the fight, but

Vince danced away and left Varona’s lusty swings hanging in the air.”

From September

10, 1955 through December 29, 1955 he won six more fights: Bob

Provizzi (W-10) in Paterson, NJ; Lester Felton (W-10) in Providence, RI; Mario

Terry (KO-3) in Boston, MA; Chris Christensen (W-10) in St Louis, MO; Ernie

Greer (KO-3) in Spokane, WA; and, Germany's Peter Muller (KO-2) in Milwaukee,

WI. Vince’s knockout of Muller was the most explosive kayo of his career. He

dropped Muller with a vicious right to the jaw after setting him up with three

straight combinations of lefts to the body and rights to the jaw. His winning

streak was now at twenty.

On December 1,

1955, Carmen Basilio was in a happy frame of mind after retaining his

welterweight title the previous day with a 12th round stoppage of

Tony DeMarco. In an article written by Joseph C. Nichols for the New York Times

regarding his future plans. Basilio said he was kindly disposed toward anybody

but Vince Martinez. "There's only one guy I don't want to fight," said Basilio.

"That's Vince Martinez. He's a pop-off who can't fight, anyway. I wouldn't get

in the ring with him for any amount of money. When I was struggling before I won

the title he wouldn't fight me for a $20,000 guarantee. Now I won't give him a

payday." Basilio said that when he did defend his title again he prefers to

meet Johnny Saxton.

Vince opened

up his 1956 campaign again on the road. He won three consecutive fights on

decision: Paolo Melis in Bangor, ME. on February 27, 1956; Miguel Diaz in Miami

Beach on April 4, 1956; and Dick Goldstein in Phoenix, AZ on May 8, 1956.

On June 16,

1956 Vince took his 23 fight-winning streak to Boston to take on former

welterweight champion Tony DeMarco in hope of earning a title shot with newly

crowned welterweight champion Johnny Saxton. Going into another fighter's back

yard was nothing new to Vince. He had been successfully doing it his entire

career. Reporter Joseph C. Nichols of the NY Times reporting on the fight.8

“Tony DeMarco of this city, a former world welterweight

champion, defeated Vince Martinez of Paterson, NJ tonight. The pair fought a

thrilling ten-round bout at Fenway Park.

The unanimous decision in favor of DeMarco was joyfully

received by the crowd of 15,000 (receipts of $115,000). Referee Jim McCarron

scored it 96-93. Judge Joe Santoro saw it 91-87, and Judge Jack Norton as 98-95.

This observer favored DeMarco 92-99, with each boxer earning five rounds.

To gain the victory, DeMarco had to rally from what

looked like certain defeat. In the early rounds Martinez, a classy boxer,

handled his opponent easily. He fired effective left hooks to the head, drove

both hands to the body and easily stayed out of the range of Tony’s wild swings.

DeMarco, however, never stopped trying. And his

perseverance won for him. He didn’t use more than a half-dozen left jabs during

the ten rounds. All he did was swing constantly for whatever target was handy.

That tactic eventually wore down his foe.

Martinez, the 7 to 5 favorite, justified the odds by

stabbing away at Tony with his left in the opening round. Tony rushed, but he

was wild and couldn’t reach Vince.

Throughout the second and third rounds the New Jersey

boxer dominated the action. He scored at long range with both hands, easily

outpunching the local boy in the exchanges.

Martinez dealt out such systematic punishment in the

fourth that a few cries ‘stop it’ were sent up by the pro-DeMarco crowd. But

Tony came out swinging in the fifth flashing long left hooks to the head and

driving both hands to the body.

He continued his wild attack throughout the sixth and

seventh, Martinez seemed puzzled in the face of his foe’s resurgence. In the

eighth Vince took over once more. His boxing kept Tony off balance. But again

Tony spurted. He took the ninth mainly because of his body punching.

The tenth, a sizzler, went to DeMarco. The rivals traded

punches willingly – by this time Martinez was finished with boxing – and the

action was furious. Things moved in Tony’s favor when he got off a long right to

the jaw. That punch drove Martinez to the ropes. It was so solid it settled the

outcome in DeMarco’s favor.”

Four months

after his winning streak was snapped Vince returned to the ring with a seventh

round technical knockout over Rinzi Nocero in Providence, RI. Five days later

Vince traveled to Miami Beach and outpointed Jimmy Ford and a month later

traveled to Bangor, ME and destroyed Don Williams in two rounds.

He started

1957 off with a bang by knocking out Mexico’s Pedro Antonio Jimenez in six

rounds in Toronto. A month later he returned to his home state of New Jersey for

the first time in nearly 18 months to take on former welterweight champion and

future hall-of-famer Kid Gavilan.

On February

26, 1957, Vince was welcome back to New Jersey with a crowd in excess of 8,500.

And the fans weren't disappointed as Martinez and Gavilan engaged in an

action-thrilled bout. Martinez came away with a 6-3-1 decision by sole arbiter

referee Joey Harrison. When Martinez opened up his attack and carried the fight

to the gallant Gavilan it was no contest. On several occasions he rocked Gavilan

with wicked two-punch combinations. Gavilan, however, refused to go away quietly

and when he was able to back Vince up he took advantage with lefts to the body

and swinging rights to the head. There were many in the crowd that thought

Gavilan had done enough to earn the decision. The fight was both thrilling and

controversial enough to warrant a return match four months later in Jersey City.

Before facing

Gavilan in a return match, Vince traveled to New Orleans to take on high-ranking

lightweight contender Ralph Dupas. The 21-year-old Dupas, dubbed by many as the

"will-of-the wisp" because his style reminded many of the legendary Willie Pep,

had turned pro at age 14 and possessed an impressive pro ledger of 64-8-5 (12).

Dupas was struggling to make the lightweight limit but remained a lightweight

because he was in line for a title shot with Joe Brown. So taking on

welterweights was nothing new for him. Ike Morales of The New Orleans Item

covered the fight.9

“Ralph Dupas stepped out of the lightweight ranks to score a

ten round decision over Vince Martinez, Paterson, NJ, tonight. Dupas weighed

141 ½ and Martinez 146 ½.

Dupas, 21, of New Orleans suffered a bad cut near the

corner of his left eye in the third round, but rallied in the final session.

A crowd of 10,800 paying a gross gate of $40,428.25 in

Pelican Stadium watched the speedy Dupas constantly beat Martinez to the punch.

In the first two rounds, Dupas had Martinez puzzled as he

moved in behind a whipping left to the body. He frequently caught Martinez off

guard with right hand leads.

In the third Martinez scored with a straight right left

and rocked the New Orleans dancer with several good right hand shots to the

head. Late in the round Dupas suffered a cut near the corner of his left eye

from a solid right hand smash.

Martinez continued scoring in the fourth, but Dupas

stormed back in the fifth and made Martinez give ground with a two-hand body

attack.

Dupas remained on the attack through the seventh and

eighth. In the ninth Martinez started trading punches again on even terms.

Martinez won the ninth with his left jabs and Dupas took the tenth with an

all-out attack. Referee Pete Giaruso scored the fight 5-4-1; Judge Lucien

Jaubert scored it 4-4-2, but awarded the fight to Ralph on aggressiveness; and

Judge Phil Gaffney had it 6-3-1.”

Long time New

Orleans Ring Correspondent Ike Morales covering the fight for Ring magazine and

The New Orleans Item had Martinez the winner 6-4. The loss to Dupas was only

Vince's fifth in 60 professional fights.

The return

match between Martinez and Gavilan on June 17, 1957 in Jersey City, NJ failed to

live up to the excitement of their first bout. Martinez won easily. He had only

one bad moment when Gavilan nailed him on the jaw with a solid right late in the

fifth round that sent him reeling into the ropes. However, Gavilan was unable to

follow up and Vince quickly recovered. From then on it was all Martinez, who had

too much speed for the faded ex-champion. Referee Paul Cavalier scored the fight

for Vince 7-3.

Vince stopped

number 7 ranked welterweight contender Larry Baker in 9 rounds in Chicago, IL on

September 11, 1957 and then traveled to Hollywood, CA on November 16, 1957 to

take on Ramon Tiscareno and came away with a convincing knockout in 6 rounds.

When Carmen

Basilio relinquished the welterweight title after he won the middleweight

championship from Sugar Ray Robinson, a World Championship Committee, consisting

of members from the NYSAC and the National Boxing Association (NBA), was set up

to determine a new champion. Six of top 10 rated welterweights in The Ring

magazine world ratings were selected to participate: Isaac Logart, Virgil Akins

(fresh off his knockout victory over Tony DeMarco) Vince Martinez, Gil Turner,

Gasper Ortega and George Barnes. The Ring’s number 4 contender Charley

(Tombstone) Smith was omitted because the NBA did not rate him. While the

eliminations were pending or in progress there was concern that efforts would be

made by promoters to label certain welterweight fights as being for the

championship. Boston promoters Rip Valenti and Johnny Buckley obtained the aid

of the Massachusetts Commission to call the fight between DeMarco and Akins as

being for the championship. championship from Sugar Ray Robinson, a World Championship Committee, consisting

of members from the NYSAC and the National Boxing Association (NBA), was set up

to determine a new champion. Six of top 10 rated welterweights in The Ring

magazine world ratings were selected to participate: Isaac Logart, Virgil Akins

(fresh off his knockout victory over Tony DeMarco) Vince Martinez, Gil Turner,

Gasper Ortega and George Barnes. The Ring’s number 4 contender Charley

(Tombstone) Smith was omitted because the NBA did not rate him. While the

eliminations were pending or in progress there was concern that efforts would be

made by promoters to label certain welterweight fights as being for the

championship. Boston promoters Rip Valenti and Johnny Buckley obtained the aid

of the Massachusetts Commission to call the fight between DeMarco and Akins as

being for the championship.

George Barnes

refused to join the tournament because he thought he could capitalize more on

his status as welterweight champion of the British Empire.

Isaac Logart

advanced when he defeated Gasper Ortega in 12 rounds on December 6, 1957. Virgil

Akins also advanced by nature of his two convincing knockout victories over Tony

DeMarco (October 29, 1957 and January 21, 1958). Six days earlier Vince also

advanced with a majority decision over Gil Turner. Below is Larry Merchant's

account of the Martinez-Turner fight.10

“Vince Martinez bopped into the ring like a 17-year-old

on his way to the finals of a jitterbug contest. Cool, loose, a little grin

etched an expression of it’s in the bag on his dainty profile.

Get im Vince, get im, a loud ringsider encouraged. Vince

winked, shuffling in a corner to get the feel of the canvas.

Vince met Turner at the center of the ring and started

dancing and feinting, flicking and darting the left. Once he landed a short

right on Turner's forehead. The round ended and he strolled to the corner

easily.

It was more of the same in round two, sticking, sticking,

sticking the left.

In the third Turner reached Vince’s body some, pressing

forward. Vince stood his ground once, firing a right into Turner. Mostly it was

stick and move, stick and move.

Vince went down in the fourth, but the referee ruled it a

slip. Turner’s manager George Katz and Turner later insisted the fourth-round

episode was the result of a left hook to Martinez jaw, flush. From my ringside

pew it appeared that way. He stepped on my foot, said Martinez later. I was off

balance. I might have been gazed but I know I wasn’t hit.

Martinez cushioned a middle-rounds respite by finishing

strongly in the 10th, 11th and 12th rounds.

Crisp right left hooks and uppercuts and right counters undid the bullying,

awkward. persistent Turner.

Judge Nate Lopinson scored it 55-55 under the 5-point

‘must’ system. But referee Pete Pantaleo and Judge James Mina concurred for

Martinez, 54-53 and 56-54, respectively. I must have been at the Cambria. I had

Martinez way ahead in rounds, 10-2 (51-42).” (10) Philadelphia sports writer

John Webster had Martinez winning 8-3-1.

With three

fighters left in the tournament due to Barnes’ withdrawal, Julius Helfand

chairman of the state commission and the championship committee arranged a draw

to determine the next pairing. Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, drew out

the names, first, Akins and then Logart, so Martinez automatically got the bye.

It was just as well that Vince was not directly picked because his manager Bill

Daly was not licensed in New York. Daly, as well as the managers of Akins and

Logart all expressed satisfaction with the way things came out.

Akins upset

the 11-5 odds by stopping Logart in the sixth round in New York on March 21,

1958, thus setting up his meeting with Vince for the vacant title.

Martinez tuned

up for his championship shot with a seventh round stoppage of former lightweight

contender Armand Savoie in Boston on May 6, 1958.

In preparation

for Akins, Martinez trained very briskly and planned to be more aggressive than

normal hoping to catch the normally slow starting Akins off guard.

Unfortunately, this strategy proved to be disastrous. In preparation

for Akins, Martinez trained very briskly and planned to be more aggressive than

normal hoping to catch the normally slow starting Akins off guard.

Unfortunately, this strategy proved to be disastrous.

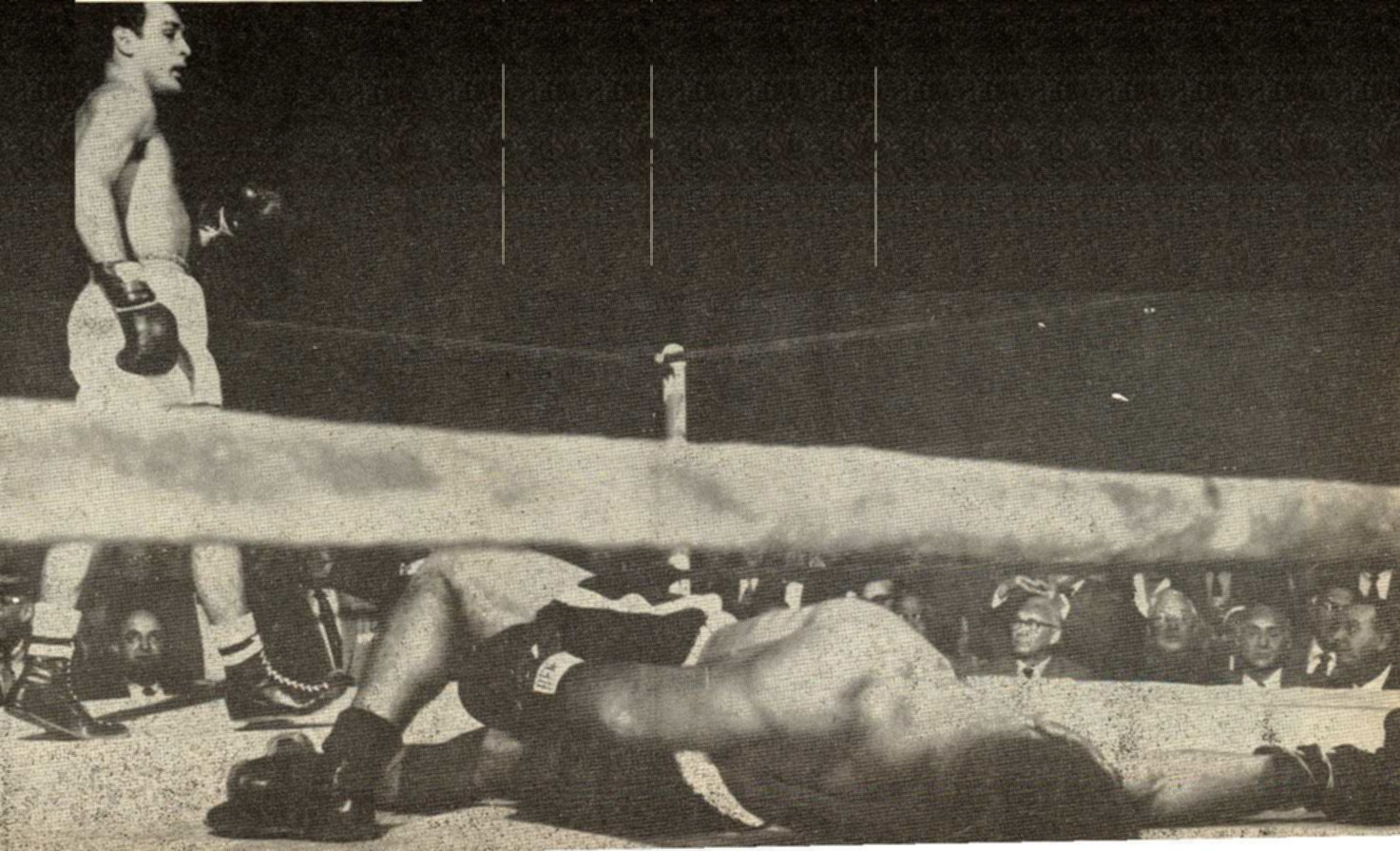

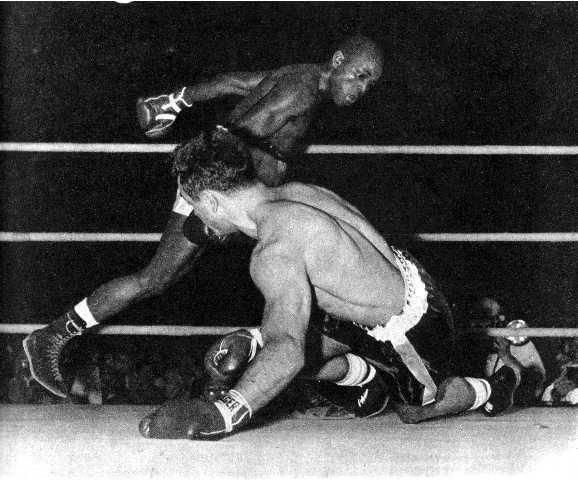

On June 6,

1958 Vince met Virgil Akins in Akins’ hometown of St Louis, MO for the vacant

world welterweight championship. The Ring’s Associate Editor Lew Eskin covered

the fight for Ring Magazine.11

Thirty seconds into the opening bell the entire pattern

of the fight was set. Martinez was not his usual…loose…fluid like, dancing

master self. He appeared rooted to a few precious feet of the canvas. He

appeared to change his usual style. He was attempting to slug it out with Akins

rather than outbox him. Virgil moved in and landed a left to the side of Vince’s

head, a solid left hook to the body, and followed with a right crossing over

Martinez’s left. Down went Vince. The fight was barely 30 seconds old when the

third punch felled Martinez. Before the round had ended he had been down four

more times. Caught cold, Vince never was in the fight after the first knockdown.

It was purely a matter of time as Akins demolished his opponent. After the

first, Akins continually stalked and punched dry the game but energy-bled shell

of Martinez. Every time that Vince started to throw his left a booming right

countered to his jaw and on more than one occasion than he cared to remember the

punch dropped him. Twice more in the third, and twice more in the fourth

session, he was slugged to the canvas before the referee raised Akins hand in

triumph at 52 seconds of that fateful fourth. With Martinez on the deck drained

of all ability to fight.

There was no question of gameness. Martinez had taken all

any athlete, trained to the peak of condition, could suffer. Kessler could have

stopped the fight in the first round and heard no criticism, but he felt that it

was a championship bout and wanted to give both participants as much of a chance

as possible. His judgment was vindicated when Martinez came back to make a

fight of it for a few moments.

The second round saw Martinez remain off the canvas for

the only three minutes of the fight. Although he was completely on the defensive

with a cut under his right eye, and nose bleeding profusely, he appeared to be

gaining strength and made one good use of his left jabs with one flurry of

combinations that were more like the Martinez the fans had expected to see.

Round three opened with Akins moving right in to keep

command. He landed a series of left jabs and two combinations to Martinez’s jaw.

Vince weathered the storm and struck back with his own lefts to the face and a

combination attack to the body and head.

It seemed that through some miracle Martinez might regain

sufficient strength to make a fight of it. His left opened a small cut over

Akins right eye.

But then the roof fell in on Vince. He just had evaded a

rush from Akins and before he could set himself, Akins ripped right through his

defenses and landed a booming right to the head. Martinez dropped as if his head

had been cut off. The end was in sight.

Martinez made it to his feet to beat the count. He was

met by a determined two-fisted avalanche that hammered him from one corner of

the ring to the other until he was driven to the canvas again through sheer

force. A weary Martinez wobbled to his feet at eight with little but gameness

left. Before he could be dropped again the bell sounded.

The fourth and last round saw a combination of the

slaughter. Too tired to lift his arms Martinez was slugged with a left and right

to the head that dropped him for the count of nine. He barely dragged himself to

his feet when another Akins onslaught dumped him flat on his back. Vince neither

heard nor saw the referee raise the hand of Akins.

The casual onlooker must have found it difficult to

understand how and why a cautious, clever, experienced boxer like Vince Martinez

could have been demolished in such a hurry by hard-hitting but slow-moving

Virgil Akins. Akins explained after the fight that he had exploited a weakness

he spotted in Martinez’s style in watching four of Martinez’s televised fights.

Martinez telegraphed his vaunted left hook. He made a peculiar movement of his

head and dropped his left hand too low before striking with it.”

Philadelphia

Boxing Historian Chuck Hasson stated, “Of course anybody can be caught cold –

but I remember after Akins KO'd Isaac Logart in the welter tourney semi-final,

he was asked his thoughts on the up-coming Martinez match and Virgil said he

would KO Vince because Vince had a habit of double jabbing, dropping his hands

and leaning back, real pretty like, and when Vince does that he just has to

throw two straight right hands the first probably missing but the second will be

on the money. Obviously Vince wasn't listening because 30 seconds after the

fight started the scenario played out just as the prognosticator Akins had

called it. I think Akins was one of the most dangerous welters in history from

1955 to 1958 (check the record).

Vince was

still ranked in the top 10 at number 8 when he returned to the ring on December

6, 1958 to win a close ten round decision over tough Stefan Redl in Newark, NJ.

Vince had to call on all his skill to beat the 25-year-old Hungarian-born Redl

by the closest of margins. Referee Paul Cavalier, the sole arbiter scored the

fight 5-4-1 for Martinez. Deane McGowan of The New York Times score card had the

fight even. But because of Martinez’ cleaner, harder punching he favored

Martinez.

Two months

later, Vince traveled to Portland, OR to meet young undefeated Portland

sensation Denny Moyer. Moyer, nearing his 20th birthday had made a

rapid rise through the welterweight ranks and was ranked number 4 and poised for

a title shot with welterweight champion Don Jordan. Moyer’s youth was too much

for Vince and he walked away with a convincing decision to clinch a title shot

with champion Jordan.

Vince, who now

lived in Florida, was out of the ring for nine months before returning against

old rival Chico Vejar on December 3, 1959. Vince jabbed and counter-punched to a

split decision. Martinez who was outweighed, 150 ½ to 153 ½ had his best round

in the third when he staggered Vejar twice – once with a jarring left-right

combination and once with a stiff left hook. The hook opened a cut under Vejar’s

eye and the eye was nearly closed at the end of the fight. Vejar forced the

fight and scored well with a body attack, but was hampered by Martinez’

counter-punching, which caused Vejar to lose his timing. The decision was split

in Martinez’ favor. The UPI scored the fight 97-95 for Martinez.

Vince entered

1960 confident that he still had enough left to make one last run at a title

shot. He planned a busy campaign. He defeated in succession: Clem Florio (TKO-6)

in Tampa, FL on April 1; Stephen Redl in a return match (TKO-5) in Paterson, NJ

on June 11; Frankie Belma (TKO-5) in Miami Beach on August 2; Bobby Shaw (TKO-4)

in Nassau on August 26; Basil Campbell (W-10) in Miami Beach on October 5; and

Enrique Esqueda (KO-9) in Monterrey, Mexico on October 15.

Age finally

caught up to Vince on December 13, 1960 in Cleveland, OH when he was stopped in

the fourth round by 22-year-old Cecil Shorts of Cleveland. Shorts, a hot

prospect, sporting a record of 16-4-1 (8) stopped Vince at 2:49 of the fourth

round. Shorts floored Vince three times in the fourth round before the referee

stopped the fight. He dropped Vince with two rights for a count of nine, then

downed him again for an eight count and finally knocked him down again with a

stiff left hook that forced referee Jackie Davis to end the fight.

Vince’s last appearance in the ring was poignant as he ended

his career in New York by outpointing Argentine middleweight Miguel Angel Aguero,

25-1-0 (14), in MSG where he first came into prominence nearly a decade earlier.

Despite his 12 years in the ring against some

of the best welterweights of his era, Vince’s features were virtually unmarked

when he hung up the gloves. This is compelling testimony to his exceptional

boxing skills.

During his retirement, Vince tried the motel

business with his father Anthony in Miami, FL. After selling the motel Vince

moved to Miramar, FL where he worked for IBM and then Operating Engineers, Inc.

It was around this time that Vince traveled to Italy where he met his lovely

wife to be, Angela.

It has been thirty years since Vince and

Angela settled in Hollywood, FL. They became the proud parents of two girls,

Patricia and Rita; and two boys, Anthony and Vincent, Jr.

Vince was one of the most popular

personalities of the 1950s and it’s a shame that he never became world champion

because he certainty had the talent.

While preparing this article I was saddened to

learn that Vince had passed away on January 29, 2003 after a long illness. May

he rest in peace.

References

1

Jones, J. The Ring, May 1953, (page 19)

2

Jones, J. The Ring, Februrary 1954, (page 41)

3

Nichols, J. New York Times, January 23, 1954

4

The New York Times, May 26, 1954

5

Miller, B. The Ring, September 1954, (page 46)

6

Blunk, F. New York Times, October 30, 1954

7

Associated Press, June 24, 1955

8

Nichols, J. New York Times, June 16, 1956

9

Morales, I. New Orleans Item, April 8, 1957

10 Merchant, L. Phil. Daily News, January 16, 1958

11 Eskin, L. The Ring, September 1958, (page 26)

|