JUNE 2005

Poem of the Month

By Tom Smario

Cinderella Man

Book Excerpt by Mike DeLisa

Entertaining Fighters and Prospects

By Adam

Pollack

Fatty Langtry: Pudgy

Pugilist of the Past

By Robert Carson

John Klein: 19th-Century

Trainer

Extraordinaire

By Pete Ehrmann

Ring Leader

By Ron Lipton

Incentives in Professional

Boxing Contracts

By Rafael Tenorio

Fight Town

Book Excerpt by Tim Dahlberg

The Regulation of Boxing

on Tribal

Lands:

Towards a Pan-Indian

Boxing Commission

By James

Alexander

Spotlight on Cut Man Lenny DeJesus

By Sam

Gregory

Dick Wipperman

by Pete Ehrmann

Jack Johnson: The Dates,

the Events, the Sources

by Stuart Templeton

Touching Gloves with...

"Irish" Art Hafey

by

Dan Hanley

|

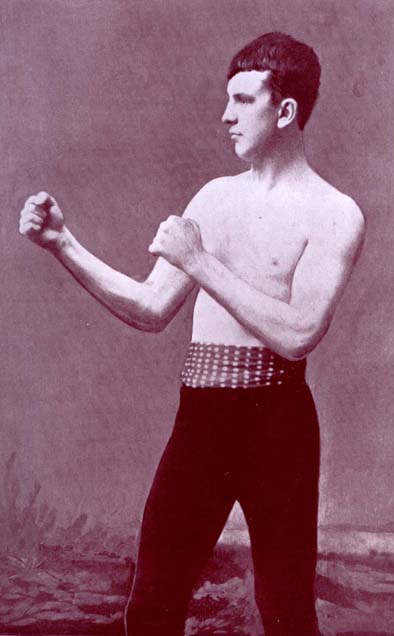

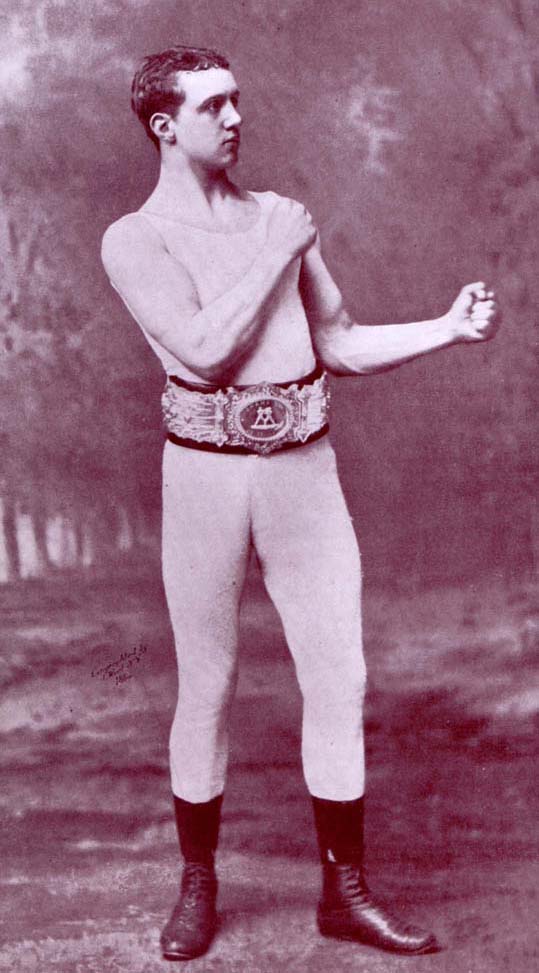

JOHN KLINE:

19TH-CENTURY

TRAINER EXTRAORDINAIRE

By Pete Ehrmann

If all of the best professional boxers in the world walked through downtown Beloit, Wisconsin, at

high noon tomorrow, they'd attract as much attention as a parade of notary

publics.

For one thing, not many

people today know or care who the best boxers are, so far has boxing fallen off

the public's radar. Besides, there would be no reason for them to congregate in

this blue-collar city of about 38,000 residents located in the middle of the

state just north of the Wisconsin-Illinois border. The big attraction in local

pro sports is the Beloit Snappers, the city's minor-league baseball team.

It was different 120 years

ago, when pugilists named Charley Mitchell, Jim Hall, Jack McAuliffe, and Patsy

Cardiff were as famous and admired throughout the land as Brett Farve and Barry

Bonds are now.

And they were familiar

faces in Beloit thanks to a local man named John Kline, and his "Manly Art

Institute."

There was no more famous

training center in all the world than that established by Kline, a fine athlete

himself who ran a mile in just under five minutes in 1884, and who once won $150

betting on himself to run from Beloit to Janesville, about 12 miles up the pike,

inside of one-and-a-half hours.

Kline was also an

accomplished skater, swimmer, and wrestler, and he could perform a double

forward flip from a standing position. A member of the Fourth Wisconsin Battery

in the Civil War, Kline had signed up when he was just 16. Boxing was one of the

diversions available in camp, and Kline was a standout with the mitts.

One day after the war,

Kline appeared in an impromptu public sparring match in Chicago and was spotted

by Charles "Parson" Davis, who managed many of that era's top boxers. Davis was

so impressed with Kline that he sent one of his charges, heavyweight Patsy

Cardiff, to Beloit to train under him. That was in 1885, and before long, the

world's top fighters were beating a path to Kline's "Manly Art Institute."

Today's boxers would

probably beat a path out of town after sampling Kline's regimen. Training

methods have changed plenty since a story in the Milwaukee Sentinel of July 12,

1891, described Kline's system as a "style of martyrdom [that] in the matter of

horrors to the physical system is almost a parallel with execution by

electricity."

At Kline's 40-acre farm on

the city's western outskirts, and his downtown gym on Sixth St., Kline's clients

were pummeled, wrestled, run, and sweated into a state of hardness designed to

help them endure the rigors of prizefights that, in those days, could go on for

three to four hours.

Kline believed that a good,

bullish neck helped a fighter withstand blows to the head. To achieve that

result, the trainer would take a heavy rope and loop it around the trainee's

neck in the middle. Then Klein and a helper would grab the ends and drag the

resisting man around the room like a lassoed steer.

Step two in achieving a

trunk-like neck was for the boxer to perform a wrestler's bridge, lying on his

back and then supporting his upraised torso on his feet and rolled-back head.

Then the 190-pound Kline would stand on his stomach and chest and bounce up and

down.

Under the circumstances, a

fellow might be forgiven an occasional outburst of expletives aimed at his

tormenters and the fates. But not at the Manly Art Institute, whose proprietor

posted signs proclaiming: "Farmyard slang or profanity will not be tolerated in

this gymnasium, by order of John Kline."

Neither was booze, except

when applied to the exterior and not the interior of the athlete. Charlie

Mitchell was the British heavyweight champion who came to Kline's to prepare for

several big contests, and each day after his workout, he was hosed down with

saltwater, rubbed vigorously, and then, according to contemporary press

accounts, washed from head to foot with whiskey and lemon.

Such a waste of his

favorite beverage must've tortured Jim Hall more than any of Kline's exercises.

A brilliant middleweight from Australia who liked his hooch so much that

sometimes he entered the ring snockered, Hall resorted to faking stomach cramps

to get a medicinal shot or two when he was at the Institute, until Kline got

wise to him.

Such a waste of his

favorite beverage must've tortured Jim Hall more than any of Kline's exercises.

A brilliant middleweight from Australia who liked his hooch so much that

sometimes he entered the ring snockered, Hall resorted to faking stomach cramps

to get a medicinal shot or two when he was at the Institute, until Kline got

wise to him.

Fighters who trained in

Beloit had a psychological as well as physical edge over their opponents. One

named Billy Bradburn had lost twice to Frank Glover when the latter had Kline as

his conditioner. Before their third match, Bradburn trained at the Manly Art

Institute and Glover didn't. As they mixed it up in the ring, a rejuvenated

Bradburn snarled, "You can't beat me tonight. I've been out to Johnny Kline's

this time!" He won, too.

Kline wasn't just an

innovator in the gym. In 1890, he was awarded a patent for a cork extractor.

He abruptly got out of the

training business in 1893, after the bibulous Hall ditched him for another

trainer just hours before his world middleweight title match in New Orleans, and

then got knocked out in three rounds by champion Bob Fitzsimmons.

"Don't mention the name

Hall in some localities about Beloit," warned the local Daily Free Press

the day after the fight. When Kline returned home, his friends threw him a

surprise party. Chances are, none of the booze on hand was used for rubbing.

After that the man the New

York Recorder called "as careful of his charge[s] as a mother of her

firstborn and as patient as Job was reported to have been," ran a tavern in

Beloit.

Kline died September 14, 1930, at age 83.

> contents <

|