February 2006

Rinsing Off the Mouthpiece

By GorDoom

Poem of the Month

By Tom Smario

The 2005 CBZ Year-End Awards

By J.D. Vena

Women to Watch For in 2006

By Adam

Pollack

INTERVIEWS:

Lou DiBella: No Joe Palooka

By Dave Iamaele

Lamon Brewster, Unplugged

By Juan C.

Ayllon

Touching Gloves with...

Clyde Gray

By Dan

Hanley

PROFILES:

Iron Mike Tyson: Myth or Monster?

By

Jim Trunzo

Jess Sandoval: The Coach Says,

"Bundle Up"

By

Katherine Dunn

The Legend of the Cuban Baron,

Ramon Castillo

By Enrique Encinsoa

Paul Thorn

By Pete Ehrman

Battling Nelson: Always Battered,

Seldom Beaten

By Tracy Callis

Kid Chocolate,

the Cuban Bon Bon

By Monte Cox

BOOK REVIEWS AND EXCERPTS:

Shadow Boxers

Photographs by Jim

Lommasson

The Iceman Diaries

by John Scully

The Boxing Bookshelf

by Dave Iamele

|

Battling Nelson:

Always Battered,

Seldom Beaten

By Tracy Callis

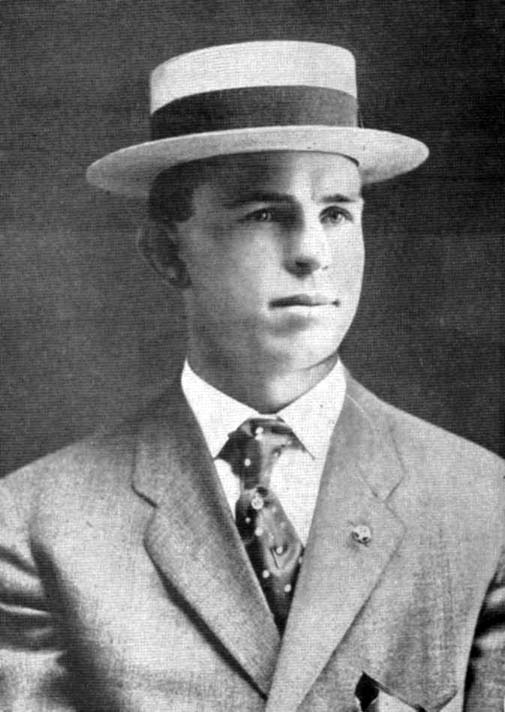

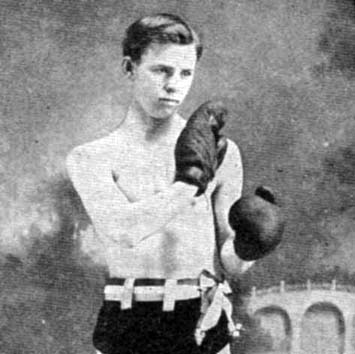

Oscar "Battling" Nelson was one of the roughest, toughest men to ever enter

the ring, no doubt about it. He could box a little but rarely did. He preferred to brawl.

His defense consisted of a thick dome that absorbed punches like a sponge absorbs water.

He got in there to do what he loved best -- fight -- to batter and get battered. He

detested the rules of the ring.

Some men are blessed with speed and quickness, others have power. Nelson had an abundance

of grit, stamina, and the will to win. McCallum (1975, p.231) described him as "a slightly

built, scrawny-looking, little man, with sunken cheeks, haunted, deep-set eyes, and a

slender, almost fragile body, a consumptive pallor, and hands too big for the rest of

him."

"They called him the 'Durable Dane,'" according to Golesworthy (1960, p.154), "and this

fighter, who was born in Copenhagen in 1882, certainly was one of the toughest men ever

seen in the ring."

"Some people say I'm not human," proclaimed Nelson (see Nelson 1908 p 73), and writer

Robert Howard echoed that, describing Nelson as "not human when it comes to taking

punishment" (1976, p.46).

Absolutely one of the most determined men to ever lace on a glove, Nelson used any means

to win. If his blows failed to do the trick, he used his vicious "scissors hook." This was

a short left hook aimed at the liver or kidneys with his thumb and forefinger extended to

give a painful pinch or stab.

NELSON GAVE NEW MEANING TO THE WORD "TOUGH"

Nelson specialized in taking it to the head (or otherwise) and punching to the body.

Gilbert Odd, the great boxing historian, asserted that Nelson earned a reputation for the

sort of body punching that could make a strong man urinate blood for a week. Nelson's left

hook was usually targeted on either the liver or the kidney and was followed by his thumb.

Said Odd, "The thin gloves of his day enabled him to pinch his unfortunate opponent the

moment his left hook landed" (see Suster, 1994, p.30).

"Few tougher men ever entered the ring" reported Suster (1994, pp.5, 26), and he added,

"He was a ruthless, dirty fighter who gave no quarter and asked none, often gouging eyes

and shifting his knee into an opponent's groin as he broke his nose with an elbow."

McCallum remarked, "Nelson would have been right at home among the bare-knuckle boys of

the gaslight era" (1975, p.232).

Bat was not a particularly difficult man to knock down. He visited the canvas rather

often. But it was well nigh impossible to keep him down. He fought coming straight toward

his man, throwing punches and taking them in. Every so often, he got nailed -- hard -- and

sometimes he went down. But up he came. Early in his career, Joe Hedmark put him down 17

times, but Nelson went the distance, although losing the decision.

Jack Robinson, an opponent in April 1903, said, "You can hit Nelson on the jaw as long as

you want, and the only thing that you'll hurt is your hands. You can hit him over the

kidneys, on the ears, on the nose, blacken both eyes, and pound his chest to a frazzle,

and he'll still grin through the blood and come back for more" (see Nelson, 1908, p.73).

"It would be difficult to find a harder man than Battling Nelson," reported Suster (1994,

p.29), and he added, "he gave a new meaning to the word 'tough.' He did not seem to care

whether he was hit or not."

"It would be difficult to find a harder man than Battling Nelson," reported Suster (1994,

p.29), and he added, "he gave a new meaning to the word 'tough.' He did not seem to care

whether he was hit or not."

According to Bert Sugar, Nelson had "the disposition of a junkyard dog." Odd remarked

about Nelson's "abnormal toughness and stamina." The writer Jack London called him "the

Abysmal Brute" (see Nelson, 1908, p.178).

A look at his career indicates he fought them all and ducked no one. On his list of

battles are Abe Attell (twice), Charlie Berry (four times), Jimmy Britt (four), Young

Corbett (twice), Clarence English (twice), Joe Percente (four), Mickey Riley (four),

"Cyclone" Johnny Thompson (twice), Ad Wolgast (three), Joe Gans (three), Terry McGovern,

Aurelio Herrera, Rudi Unholz, George Memsic, Martin Canole, Eddie Santry, Kid Ryan, Ole

Oleson, and Charlie Neary.

Nelson also had what he called his "Colored Morgue," which consisted of the black fighters

he engaged and defeated. This collection of fights included Christy Williams, Ed Burley,

Feathers Vernon, Kid Griffo (Bat won twice), and Joe Gans (Bat won twice).

McCallum wrote: "Never a great slugger, Bat beat the greatest sluggers of the day: Young

Corbett, Herrera, Hyland, Hanlon. [...] Never a particularly gifted boxer, he kayoed the

top craftsmen: Canole, Spider Welsh, Britt, Gans. He held the masterful Abe Attell to a

15-round draw" (1975, p.32).

Nelson talked sometimes of his ring career and told such stories as "I got jobbed in my

fight with Eddie Santry" at Chicago in November 1901, because Eddie talked the referee

into thinking he was supposed to win (a fixed fight); Mike Walsh, a 6-foot middleweight,

blurted "I'm not here to lick kids" when he saw the slender Nelson come into the ring

December 1901 in Chicago. "That's good," said Bat, "'cause I ain't no kid." Walsh ended up

on the floor with his head across the ropes.

On June 16, 1903, in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, every time Bat knocked Young Scotty down

("about half a dozen times"), the lights in the building went out. "His head hit the floor

with such force it jarred the building and I guess turned off the electric light switch."

He encountered a setup in Michigan City, Indiana, on August 26, 1903, against Eddie

Sterns. Nelson said he knocked his man down frequently and, each time, he was given about

15 seconds to rise instead of 10. Bat was told by the referee that if he kept it up, he

would be disqualified -- and he was.

Against Kid Sullivan in Baltimore on June 2, 1905, Nelson had won the first three rounds,

but something was smeared on Sullivan's gloves prior to Rounds 4 and 5. It hurt Bat's eyes

and he had trouble seeing. Just to make sure, before the last round, more "stuff" was

slathered on the gloves, and Bat said he was almost totally blind and could not tell

Sullivan from the referee.

Then there's the story of how Bat's father talked with him in 1901 about not fighting

anymore. Bat told him he'd think it over. They went downtown to a bar, where someone was

praising a fighter by the name of Frankie Colifer, from Pullman, and declaring that no one

in Hegewisch (Nelson's town) could fight, whereupon Bat's dad yelled out that he'd bet

$1,000 his son could beat Colifer (see Heinz, 1961, pp.303-304). They fought on January

13, 1902, and Nelson knocked Colifer out in five rounds.

Bat once called Aurelio Herrera "the greatest whirlwind fighter that ever lived."

Bat once called Aurelio Herrera "the greatest whirlwind fighter that ever lived."

"He could hit like a trip hammer," Bat added, "and he was so fast that his arms worked

like piston rods on the New York Central." Not only could he hit, but he could take it,

too. His weakness was that he didn't train sufficiently.

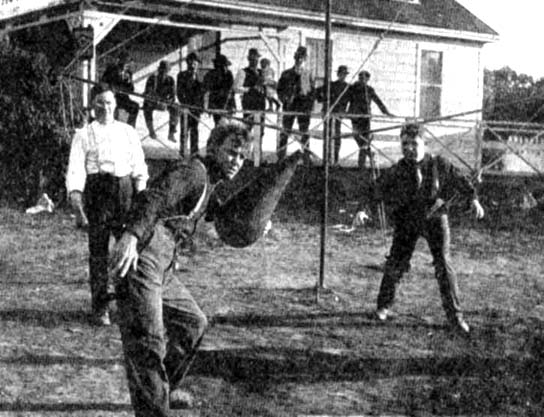

Bat took on the powerful Mexican, and for this fight he got himself into excellent

physical condition. During the contest, Bat got blasted with a shot that would paralyze

most men and, indeed, Nelson felt it. In this September 1904 fight in Butte, Montana,

Nelson was propelled sideways to the floor by a blow, and his eyes were glazed as if he

were hypnotized and in a trance. But he came back to beat his man in a long fight of 20

rounds.

YOUNG CORBETT AND JIMMY BRITT

Following his fight with Herrera, Bat tangled with Young Corbett (William Rothwell), and

it turned out to be a confidence builder. When he won, he felt he could defeat the

lightweight champion, Jimmy Britt, too. Nelson always insisted "Young Corbett was one of

the greatest fighters this country has ever seen." He was a terrific hitter and brainy as

well. He tried to upset an opponent with pre-fight talk, making insulting remarks about

his fighting skills and also saying personally degrading statements. Then, during a fight,

he made belittling wisecracks. This tactic usually got a man out of control. Then Corbett

would have an easier time boxing him and pounding him.

In their first fight, in November 1904, Nelson worked around Corbett until he discovered

that his weakness was his wind. Then Bat counted on his ruggedness to carry him through

and waded into his man with one barrage of body blows after another. This kept up round

after round. Bat paid a price by absorbing many stiff punches, but his attack to Corbett's

middle eventually paid off. Corbett collapsed in Round 10 and stayed down.

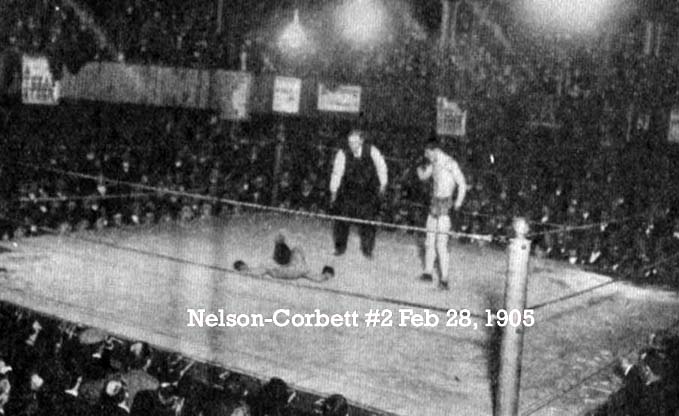

They met again in February 1905, and though Corbett showed well early,

Nelson scored a knockdown in Round 4. Bat played Corbett's old game. He walked near his

fallen foe and said, "Get up and not go down until you're hit." Corbett got up, all right,

and fought like a wildcat. According to Nelson, a hard right was the "worst punch I ever

took" and it broke a rib. This fight ended like the first with Corbett knocked

out in the ninth.

They met again in February 1905, and though Corbett showed well early,

Nelson scored a knockdown in Round 4. Bat played Corbett's old game. He walked near his

fallen foe and said, "Get up and not go down until you're hit." Corbett got up, all right,

and fought like a wildcat. According to Nelson, a hard right was the "worst punch I ever

took" and it broke a rib. This fight ended like the first with Corbett knocked

out in the ninth.

In September 1905, fighting for the lightweight title in Colma, California, Jimmy Britt

delivered blow after blow on Nelson's tough dome. Jack London wrote that Britt landed six

punches to Nelson's one. "In the first round Britt hit Nelson half a dozen blows. At each

blow Nelson was coming in. The blows did not stop him. Then Nelson hit Britt, and Britt

was staggered."

This was the story. For 18 rounds Nelson kept boring in and Britt couldn't stop him.

Britt hit his man and moved. When Nelson got inside, the stomach,

kidneys, and face were targets. At times Britt

appeared weak enough to collapse but somehow kept going. After 18 rounds like this, Britt

caved in and Nelson put him in "lala land." The fewer number of blows landed by the Dane

had counted (see Nelson, 1908, pp.178-183).

This was the story. For 18 rounds Nelson kept boring in and Britt couldn't stop him.

Britt hit his man and moved. When Nelson got inside, the stomach,

kidneys, and face were targets. At times Britt

appeared weak enough to collapse but somehow kept going. After 18 rounds like this, Britt

caved in and Nelson put him in "lala land." The fewer number of blows landed by the Dane

had counted (see Nelson, 1908, pp.178-183).

Ashton Stevens, writing for The San Francisco Examiner (September 10, 1905)

testified, "This duel between Jimmie Britt and Battling Nelson had a nerve-wrecking

shudder for every moment of the 52 minutes of actual fighting. It was a sight such as I

hope never to see again." Stevens went on to describe the end:

"When the right fist of

Nelson emerged from a tangle of blows in the 18th round and came invincibly against the

jaw of Britt, and the champion of his lightweight kind fell numb against the ropes and

sank to the canvas floor, his lips geysers of blood, his tongue a protruding, sickening

blade of red, the mob went mad" (see Nelson, 1908, p.185).

NELSON BATTLES GANS

In a title defense a year later in Goldfield, Nevada, Nelson met one of the smoothest,

slickest boxers that ever laced on a glove: Joe Gans. Each man applied his own ring style

in the fight. Gans boxed cleverly, controlled the fight during the early rounds, and laid

on the licks. But Bat kept coming forward. As the fight progressed and Gans tired, the

Battler broke through Gans' defense and delivered his own brand of unruly punishment.

However, Joe was tougher than anyone realized. He took what Nelson threw, weathered the

storm, gained his second wind, and resumed his assault on the rugged foe. Finally, in the

last round, after 41 rounds of gifted boxing by Gans and roughhousing by Nelson, Bat

resorting to fouling and referee George Siler disqualified him.

Johnston noted, "Nelson's style of fighting, which he was able to adopt because of his

almost superhuman endurance, tended to slow up the fighting and to prevent a man who

fought as Gans did from showing the keen edge of his cleverness.

"From the beginning of the battle to the end, Nelson kept boring in, shaking off the

straight-arm blows with which Gans met him, clinching and pounding the body with short-arm

jolts.

"From the beginning of the battle to the end, Nelson kept boring in, shaking off the

straight-arm blows with which Gans met him, clinching and pounding the body with short-arm

jolts.

"On occasion, this is an effective way of fighting over the long-distance, but it does not

make a snappy and interesting battle. Throughout the melee Gans did the better fighting.

He snapped home his left jabs with smoke enough to have stopped any man less durable than

Bat. He would follow his lefts with lightning-like rights when he got the chance, but he

never could quite bring down the dogged, tow-headed boy in front of him, who never took a

backward step and absorbed all the punishment the champion could inflict" (1936, p.318).

Nelson avenged himself against Gans in July 1908, when he knocked out the not-so-healthy

great in 17 rounds in Colma. Writer Bob Smith recorded: "Of Nelson it must be written that

he is the most wonderful athlete of his inches in the world. He hardly drew a long breath

during the fight. Added to the fact that he seems absolutely tireless is the additional

quality of being insensible to pain. He took blows from Gans which seemed to have enough

power behind them to fell an ox. When they landed Nelson merely shook his head and rushed

in for more. Each time Gans tried to mix matters and put in his best efforts to stop the

Dane the latter came back fighting all the harder. He was relentless in his attack" (see

Nelson, 1908, p.229).

Two months later, in September, Nelson did it again, this time in 21 rounds. Gans did all

right for himself in the early going of these bouts, but much of his skill was gone at

this point, and as he tired he became vulnerable to all of Nelson's aggressive efforts.

Some time later, Gans said, "Nelson is the best lightweight over a distance that I ever

saw, and I have been fighting as long as or longer than anybody in the game today. [...]

He is simply impervious to punishment" (from a story published in The Chicago Sunday

Examiner, September 20, 1908; see Nelson, 1908, p.217).

NELSON-WOLGAST II: "THE

NELSON-WOLGAST II: "THE

DIRTIEST FIGHT EVER"

On February 22, 1910, Nelson and Ad Wolgast met in a grudge battle "most foul," as

Shakespeare would say. Fouls galore were the order of the day, and they were permitted

-- why not? Two bad boys were tangling in a contest that would wear out any referee.

They had met once before, in 1909, in a 10-rounder that most observers thought Wolgast had

won. They would meet again in 1913 in another 10-round contest with a similar result. But

this 1910 encounter was a war. Both men were never-say-die gladiators who were ready,

willing, and able -- and durable. Wolgast was younger by nearly six years. In addition,

The Tacoma Daily News reported he had fought 69 bouts while Nelson had engaged in

92. The wear and tear was piling up on Bat while Wolgast was yet a warrior at his best.

The fighting was fierce. Defense was tossed out the window. Aggression was the order of

the day. Bat was better during the early rounds but the younger, relentless Wolgast took

it all and gradually turned the tide his way with some stiff punching. In the face of

concerns by the referee, Nelson insisted on staying in the fight, round after round. But

by Round 42 his eyes were so swollen that he could hardly see, and the battle was stopped.

Suster reported: "It was the dirtiest fight ever held for a world championship under the

Queensberry Rules, which both men disgraced in an obscene orgy of eye-gouging,

rabbit-punching, elbow-thwacking, and ball-busting. The bout was bloody and brutal" (1994,

p.31).

Bat got the worst of this one but complained when referee Ed Smith stopped the fight.

Ringsider W.O. McGeehan wrote, "For concentrated viciousness, prolonged past 40 rounds,

this was the most savage bout I have ever seen" (see Suster, 1994, p.32).

Bat got the worst of this one but complained when referee Ed Smith stopped the fight.

Ringsider W.O. McGeehan wrote, "For concentrated viciousness, prolonged past 40 rounds,

this was the most savage bout I have ever seen" (see Suster, 1994, p.32).

Robert Howard wrote, "The iron man has fought since time immemorial -- with but one

thought in mind -- to get to his foe and to crush him" (1976, p.11). He was truly

describing Bat Nelson.

In a 1975 survey of old-timers conducted by John McCallum,

Oscar "Battling" Nelson ranked as the No. 5

all-time lightweight (1975, p.323). Nat Fleischer also ranked Nelson as the No. 5 all-time

lightweight. Charley Rose ranked him as No. 8. A recent poll conducted by International

Boxing Research Organization (IBRO) ranked Nelson No. 13 on the all-time lightweight list.

In the opinion of this writer, Nelson could fight with any of the all-time greats due to

his toughness and durability, and he certainly ranks among the greatest iron men of all

time.

Contact Tracy Callis at

editors@cyberboxingzone.com.

> contents

<

References:

Golesworthy, M. 1960. The Encyclopaedia of Boxing. London: Robert Hale Limited.

Heinz, W. 1961. The Fireside Book of Boxing. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Howard, R. 1976. The Iron Man. West Kingston, RI: Donald Grant.

Johnston, A. 1936. Ten -- And Out! New York: Ives Washburn.

McCallum, J. 1975. The Encyclopedia of World Boxing Champions. Radnor, PA: Chilton

Book Company.

Myler, P. 1998. A Century of Boxing Greats. New York: Robson/Parkwest Publications.

Nelson, B. 1908. Life, Battles and Career of Battling Nelson. Hegewisch, IL:

Battling Nelson.

Suster, G. 1994. Lightning Strikes. London: Robson Books Ltd.

|