. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNALTable of Contents

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL |

May 2001 Table of Contents |

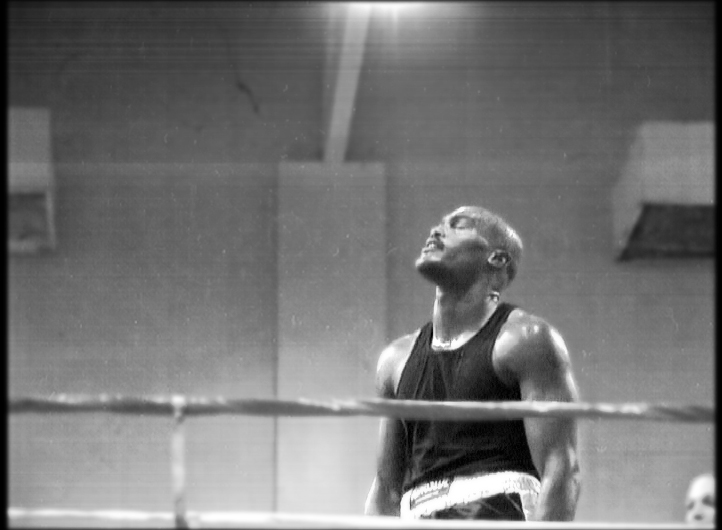

Photo: David Zerull |

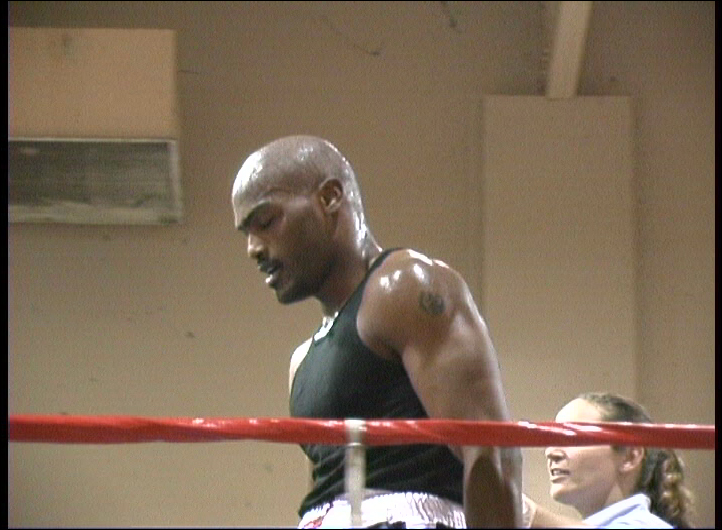

CRY UNCLE Heavyweight attorney Justin Sanders wins the Los Angeles Golden Gloves 47 years after Olympic champion Ed Sanders ó his famous, but forgotten uncle ó was killed in the boxing ring BY JAMES A. MEROLLA LOS ANGELES ó Justin Sanders has to hide the bruises under his eyes. The massively-built attorney really shouldnít come to his conservative corporate law firm looking this way every day, so he keeps his dark glasses on and uses a little of his girlfriendís makeup to cover up the welts. Sanders keeps getting banged around by the brutal hooks of more experienced sparring partners who have taken to showing the young buck lawyer a thing or two about boxing at The Los Angeles Boxing Club five nights a week. A smart attorney should know better than to enter such a hard game at such an advanced age and a man like Sanders should know the dangers even more. The sport killed his famous uncle Ed Sanders, the 1952 Olympic boxing champion, who was maybe the finest amateur heavyweight this country has ever produced ó 22 years before Justin Sanders was even born. His uncle died at 25, the same age Sanders is now. Yet, in a sport of flat fees and even flatter noses, he is undaunted. Despite growing family concerns, Sanders wants to hang something on his wall next to his law degree ó a Golden Gloves plaque. It is a material pittance compared to the physical perils, and he knows it. Sanders says itís crazy to be a pro boxer and he doesnít even want to try that. "I couldnít do this without head gear," Sanders says. Then, he spars again. Bam. Bam. Bam. A jab for a hook. Then, another. The sweat flies off his shaven head. There are no contingencies here. Sparring partners get their blows in pro bono. Who wouldnít want to take a free series of shots at a lawyer? "Dang," he adds of the buzz and the ringing, a one-word testimony to what he still must learn. His trainer "Bird" Jensen tells him he could be a good boxer in a year ó he has the strapping physique and the head for it. Sanders may not have a year to give. "Heís learning," Jensen says. "Boxing is a time-consuming sport. You canít learn overnight. But the man is a real fast learner, if he sticks with it." But Jensen wonít push his large novice too fast. He knows the dangers. "Iím the guy who calls the shots," he says. "If I donít think heís ready at that time, he wonít fight. If I think heís ready, he will." When Justin Sanders entered a boxing gym for the first time ever in October to begin a strange odyssey to reclaim the sport that claimed his uncle and decimated his family, he stirred up heavyweight ghosts, long dead and virtually forgotten by the outside world. At 6í5" and 225 lbs., Sanders has long limbs and an even longer memory, and a family pride which goes back at least a century. Hayes Sanders, Justinís grandfather, was a quiet man of enormous dignity, a World War I veteran who fought in the Battle of the Argonne Forest. He hauled garbage in Los Angeles for almost 40 years. Hayes Sanders would carry anything to help carry his children out of Watts. "He had a very hard life," Sanders says. "But he never talked too much." Hayesí son Ed, who grew to 6í4" and 220 lbs., chose football first. He played end on the great Compton JC team that had Hugh McElhenny in the backfield. Pretty soon, he was the best collegiate boxer in the country and the all-Rocky Mountain Conference end at Idaho State. But the Korean War had started and he went into the Navy and, soon, Ed Sanders was the best amateur boxer in the entire world. In the late summer of 1952, Sanders went to the Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, facing future heavyweight champion Ingemar Johannson in the gold medal match. When Johannson first laid eyes on his opponent he started running backwards and never stopped. He became the only Olympic boxer ever disqualified for "not trying." In his autobiography, Johannson blamed the referee for his failure. Sanders looked unstoppable. The good-natured, deeply religious heavyweight then made a decision which may have proven his undoing. Rather than turning pro immediately ó something the Navy refused to let him do for at least a year ó Sanders remained an amateur in an attempt to win the National Golden Gloves title in 1953. In the finals, he faced the only other fighter on earth who could have hurt him ó a young monster named Sonny Liston. No one really knows if Liston did damage to Sanders that came back to haunt him. Sanders was defeated for the national crown and some say he possibly suffered a head injury that may have led to his demise. Russell Sanders says otherwise. Ed Sandersí devoted son has spent 20 years of his life documenting and spreading the legacy that was his fatherís. He said the Liston-Sanders decision was split and that Liston did not look that impressive. Having nowhere else to go but up, and with a new wife named Mary and that baby son to support and a rare chance to get out of Watts permanently ó decades before boxers signed guaranteed, big-money contracts with cable networks, years before black athletes could make a living breaking down barriers in all the major sports, Sanders went to Boston with the Navy fleet and turned pro. He went undefeated in his first nine fights within a year. The mountain that was Ed Sanders crumbled on December 12, 1954. Instead of becoming New England heavyweight champion, Sanders collapsed in the opening seconds of the eleventh round during his fight with veteran Willie James. It seemed impossible to believe, but the Olympic champion ó as big as George Foreman would be two decades later ó was carried out of the ring. A four-hour operation to relieve a blood clot failed to revive him. He died the next day at Massachusetts General Hospital at the very moment his young wife Mary, who had been at ringside, entered his room to see him. Sanders became boxingís eighth fatality in 1954, its second within three days. "Iím terribly sorry," James kept repeating after he had visited the hospital, according to a next day story in the Los Angeles Times. "I didnít think I hit him that hard. I hit him an uppercut in the 10th round, the hardest punch of the fight. I didnít realize he was badly hurt at the time he went down. I thought he would come to in a few minutes." James said Sanders acted "very tiredí when he came out for the 11th round. He pointed out that the Navy veteran had never fought more than 10 rounds. "He loved fighting," Mary Sanders, the thin young woman from Idaho reportedly told the Boston Globe the next day. "He loved it very much. I never disapproved of his fighting, and I never was afraid that heíd get hurt." Russell Sanders disputes these quotes, also. He says they were made up, at worst, and inaccurate, at best. Sanders said his mother didnít want her husband to fight anymore after a rugged ten-round draw with veteran Bert Whitehurst, just before the James fight. Justin Sanders doesnít have all the details his cousin in Idaho has. "My Dad used to tell me about him when I was a kid. He would say Ďyour uncle won the Olympic Gold Medalí and heíd show me pictures of him," Justin Sanders says. "When I was young, of course, I truly didnít understand the magnitude of what he had accomplished or of his death. Ed was a legend in the family. My Dad was only 12 when Ed died. He says he remembers that they gave Ed a twenty-one-gun salute at the cemetery. It was the only time he saw his father cry." Justin remembers that the specter of death haunted grandfather Hayes. Two of his children died early. The oldest child Winnifred, died at age 11 in 1939. Ed died in 1954. His wife Eva died in 1963. Justinís Dad is the only one left alive. "Edís mother Eva was against his boxing and could not watch his fights," Sanders says. "She would sit in the crowd and cover her eyes. His death was her worst nightmare come true and she pretty much gave up on life after his death." When Sanders was a child, he was proud to tell friends about his famous Uncle Ed. "My Dad looked up to Ed. He said Ed was ĎGod-like,í a mythical figure. I was not sad. Just proud. At the time, according to my Dad, Ed was going to go on and beat Rocky Marciano (the undefeated world champion in 1954) when tragedy struck," he adds. But some family members still believe that either the hammer-like fists of Liston or another kind of hammer did Ed Sanders in long before he met Willie James. "I had always understood, whether correctly or not, that he had died primarily because of a previous brain condition, not the result of a knockout loss," Sanders says. "I had heard something about him, a family story, that he had been hit pretty hard with an ax while playing with it as a kid. I guess they played pretty rough." All through his brief life, Ed Sanders never abandoned his little brother Stan, Justinís father. He wrote him many letters, urging him to study hard and read and make something of himself in an ever-changing post-War world. Stan Sanders listened. When the letters stopped, Stan Sanders went to Whittier College, then Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, then Yale Law School to obtain his law degree. His educational choices exceeded his personal ones. His marriage to Justinís mother was a tougher road. "I moved over to my Dadís when I was 12 after my Mom became disabled," Sanders adds of life in the Crenshaw district. "My parents were divorced when I was two. My Dad is the greatest father ever, my role model." The two Sanders boys ó his brother is named Ed, after Big Ed ó continue to support their disabled mother financially. "It is difficult, but I donít complain," he shrugs. Sanders himself was a poor student as a child. He attended a "preppie" Catholic high school, which he says made him uncomfortable because he didnít think he belonged around "intellectuals" in his youth. He went to Morehouse College in Atlanta, the nationís only predominantly male, all-black college. "Morehouse transformed my life," he says. "I learned to be a man there." Sanders graduated phi beta kappa/magna cum laude in the top five percent of his 1997 class. Sanders passed the Bar in November at USC. Now, he is trying to raise it. "As I learned more about Ed and his career, his death actually began to hurt me personally although I never knew him," Sanders adds. "Itís really hard to believe that such a thing could happen to a guy so destined for greatness. I was losing sleep over it a few months ago. I think way too much. I have a picture of Ed in my office next to my desk." Sanders says his father doesnít have a "huge fear" of boxing, but he never pushed his boys to it either. They used to fight around the house with a pair of old boxing gloves. Among his cousins, however, boxing has always been forbidden. "They are skeptical of me fighting," he says with typical massive understatement. "My Dad watches big boxing matches, but he is not a boxing enthusiast. My stepmom is worried Iíll mess up my face. My Dad supports it as long as I donít go pro. I think they are getting concerned now that itís really here and Iím sparring a lot." Sanders has been running several miles nearly every day and going to the gym five times a week for two hours each night. At the end of March, all of the hard work paid off. Sanders just won the Los Angeles Golden Gloves super heavyweight title, sub-novice division (newcomer), defeating several men by decision, the first of whom weighed upwards of 275 lbs. "Itís just a really amazing feeling," Sanders said. "The whole thing was like a dream. My family was all there screaming and yelling, especially my Dad. He knew how bad I wanted it." Does he worry? "Yes, all the time. I worry about how much Iím putting into it. I worry about what people think. I fear losing in front of my family. I worry about my health. I worry about who Iíll be fighting. I fear running up against another Sonny Liston. I worry that skull weakness is hereditary." And what will all this worry lead to? "Validation. I want something to hang on my wall. I donít really have something to hang on the wall because I quit sports (the result of a bad knee injury playing high school football). I would lay awake nights thinking of what I could do to get back into athletics. I prayed to God to help me quench the desire. It had consumed my thoughts and made me depressed. God sent me boxing. I am so very happy to have that trophy at home." He is more like his great uncle than even he knows. The day after he died, his aunt Mary allegedly told the Boston Globe how intense her husband would get before a bout. "He would get all wrapped up in himself. He took it so seriously," she said. "It was like talking to a wall. Sometimes he didnít answer me. But I understood." Russell Sanders said his father was introspective before a fight, but not unresponsive. The nephew is that way, too. "I spend a lot of time reading and analyzing my own thoughts," Sanders adds. "I try to achieve and maintain peace of mind. Peace of mind is the most important thing to me in life," said the lawyer who is now a boxer. But first, there is more fighting to do. "My thumb is swollen like crazy," Sanders said. "Iím going to take a week or two off and then get back in there. Iím still hungry for more fights. "Sometimes, people come up to me and say, ĎI knew your uncleÖí or ĎI saw your uncle onceÖí I wanted to document his achievements and let everyone know about him. I wanted more than just family stories. I feel like his life has passed in the wind." James A. Merolla is a feature writer for The Sun Chronicle in Attleboro, Mass., and a former writer for Ring magazine.

|

Photo: David Zerull |

| Schedule | News | Current Champs | WAIL! | Encyclopedia | Links | Store | Home |