| |||

| COMMENT | CONTACT | BACK ISSUES | CBZ MASTHEAD |

|

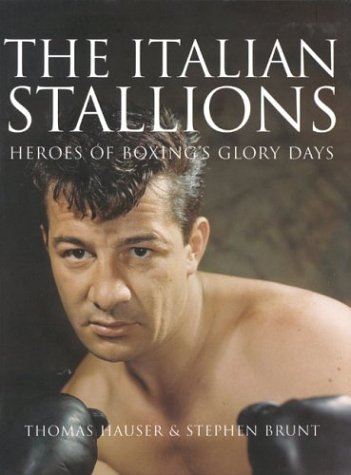

The Italian Stallions: Heroes of Boxing’s Glory Days by Stephen Brunt and the Writers of Sport Magazine Introduction by Thomas Hauser Sport Media Publishing 224 pages, $34.95

Reviewed by Brett Conway

Upon opening the book The Italian Stallions, we readers see a full-page photo of a banquet hall. Our eyes notice chairs encircling a podium and containing men in suits. On the podium, we see a husky man with dented features wearing a suit. All eyes are on this man. Above him, there is hanging from a wall an enlarged magazine cover bearing his picture. In this cover photo, he is standing shirtless and holding up fists wearing boxing gloves. On the upper left of this cover, we see the word “Sport." The man addressing the banquet and posing in the photo is heavyweight boxing champion Rocky Marciano. The caption of the photo tells us he is addressing the editors of Sport magazine for being the sportsman of the year in 1955. We turn the page of the book and see another full page photo. Occupying a row of chairs at a boxing match are three men in suits. The man on the far left is engrossed in the action before him. The caption below the picture explains that this man is J. Edgar Hoover and that he is watching a fight between former lightweight champion Tony Canzoneri and Frankie Klick. Turning our eyes to the next page, we see an essay by boxing writer Thomas Hauser. The essay is called “When Boxing Mattered.” This new book, edited by the author of the boxing classic Black Lights, Thomas Hauser, and by Globe and Mail columnist and author of Facing Ali, Stephen Brunt, contains over a dozen articles and well over one hundred photos taken from the pages of Sport, a magazine that both predated and influenced Sports Illustrated's style of sports writing. This book depicts a time when out of all the sports in America, boxing - along with baseball - was the most popular. It recounts the era between the heavyweight reigns of Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali, when Italian-American fighters dominated boxing. How dominant were they? Between 1945 and 1959, they were involved in thirteen Ring magazine fights of the year. From Primo Carnera to Willie Pep, Rocky Graziano to Rocky Marciano, Jake LaMotta to Carmen Basilio, this book reminds us of an era when fans could identify with a boxer not because they read about him in the paper, but because they saw him living in their neighborhoods. It reminds us of an era when boxers could still earn a living fighting in local boxing clubs, an era when television tapped into the demand for televised fights and created stars like Carmen Basilio at the expense of the majority of pugs plying their trade away from television, an era when politicians would sit and listen to a boxer “express himself” (Jake La Motta’s words) in a ring and in a banquet hall - for back then, as Hauser insists, boxing mattered. This book matters, too, and should be on the bookshelves of anyone who cares about boxing. The book has eight chapters containing photos and prose, an introduction, and an epilogue. It also contains an appendix with the fighters’ ring records. It does not simply reprint articles from Sport, however. Both Hauser’s short introduction and Brunt’s opening chapter (“The Exodus”) and epilogue explain the historical context and socioeconomic factors that led to the rise and decline of Italian fighters in America. They detail the political climate in Italy that compelled millions of Southern Italians to move to the United States, summarize the careers of the fighters covered in the articles, and explain the decline in the number of Italian-Americans boxing today. Chapters two through eight contain articles taken exclusively from Sport. Profiles of heavyweight champion Primo Carnera and lightweight champion Tony Canzoneri make up chapter two (“the Early Days”); profiles of heavyweight contender Roland La Starza, light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim, and Joey Giardello make up eight (“the End of an Era”); but the real feast lies in between: Willie Pep, Rocky Graziano, Jake LaMotta, Rocky Marciano, and Carmen Basilio. But when we scan the contents page, we see Basilio’s name and not the others. Instead we see Guglielmo Papaleo, Thomas Rocco Barbella, Giacobe LaMotta, and Rocco Francis Marchegiano, for Hauser and Brunt want to remind us that these are Italian fighters who - in order to avoid prejudice, get good fights, and to have their names spelled correctly in the sports pages - had their Italian names Americanized (When Marchegiano became Marciano, he said, “at least it sounds Italian”). The boxers are not the only stars in this book. Its articles were written by many respected writers: W.C. Heinz, Barney Nagler, and Rex Lardner, for example (more on that later). Its photos are stunning, reminding us of what we have lost with the use of color film and the saturation of the boxing ring with advertisements. Without the corporate rubber stamp of a beer company to distract us from the fighters, the battle in the ring seems primordial. The image of Marciano, exhausted, teetering on one foot, knocking out Don Cockell on page 161; the photo of Basilio, staggered, and Gene Fullmer, confident and in charge, exchanging punches on page 188; the over two dozen photos of Pep and Sandy Saddler, laid out between pages 62 and 71; they create a visual narrative of their four fights - these photos are rare and breath-taking and show a brutality that, like it or not, is missing from many of today’s ring battles. Each chapter ends with an interesting epilogue, summarizing the fighter’s life from the time of the article until the present. This book does not only focus on the careers of the more famous fighters such as LaMotta, Graziano, and Marciano. It also profiles the fighters who are often praised but seldom discussed in print other than as a subject of an anecdote: lightweight champion Willie Pep and welterweight and middleweight champion Carmen Basilio. Carmen Basilio is remembered as a great and exciting welterweight champion who struggled against middleweights like Sugar Ray Robinson and Gene Fullmer. Several times I have seen highlights of these fights on an HBO documentary about Sugar Ray. Not surprisingly, Basilio is depicted as Robinson’s foil: he was the slugger; Robinson, the stylist. After hearing from Howard Cosell that nine out of ten journalists chose Robinson to regain his middleweight title from Basilio in their rematch, Basilio sneered, “nine of ‘em are wrong,” and stormed off. This angry Basilio is not found in The Italian Stallions. He is thoughtful and articulate, especially when it comes to discussing his profession. In Ed Linn’s October, 1957 profile, Basilio says, I used to take three punches to land one, because I didn’t know how to do it any other way. These are things you have to learn through experience. After a while, you find yourself making the right moves to slip punches or to feint a man off balance; you find yourself recognizing the other man’s feints and countering certain punches very effectively. It’s a hard thing to explain because what you learn is in your muscles and your reflexes as much – and maybe more than in your mind. (174) Talking about the affection that develops between boxers in the ring, he says, “you can gain respect for the other guy. You look up to him” (175). He sounds less like a palooka and more like Cus D’Amato; his ethos is less like Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky and more like W.C. Heinz’s The Professional. In this book, the boxers come off looking good because the writers treat them with respect. This respect is reflected in their essays. In Linn’s article abut Basilio, instead of bemoaning how a lowly boxer has become a role model to children, he writes, “[Basilio’s neighbours] know him to be the kind of example that athletes, for reasons we’ve never been fully able to accept, are supposed to be” (178). The writer eschews the chance to act as a moral censor as we often find in boxing profiles these days. Instead, he produces excellent prose. Here is a recap of the second Robinson-Basilio fight as seen by the editors of Sport: The battle showed Robinson as the genius he is at learning from a first fight. He held and boxed in spurts, moved in and out, missed more punches than was once his habit, but scored because Basilio, surprisingly, stood up, took punches and went into his crouch only when hurt. At the end, his left eye looking like abused liver, Carmen knelt and prayed. Later, in his dressing room, loser Basilio retched from swallowed blood. (186) The writers use these vivid images to catch, in less than one hundred words, the essence of one of Basilio’s five Ring fights of the year. Other than a lack of brief biographies of any of the writers whose works are being anthologized, the book shortchanges us for not adequately explaining its title: The Italian Stallions. The title alludes to those boxers who dominated boxing from 1945 to 1959, a period when Italian-Americans were integrating into American society after having served America in World War II. Since then, as discussed in the epilogue, Italian-Americans have not needed to fight to make a living. Like the Jews and the Irish in America, the Italian-Americans enjoyed upward economic mobility and assimilated into the melting pot of America, thus making the risky trade of boxing undesirable. Indeed, by the mid-1960s, Italian-American boxers are no longer Italian-American but American in the pages of Sport. The “swarthy” (205) fighters of 1950 are, in 1964, “white” (209). They became racially invisible and part of the fabric of American society (whereas black and Mexican-American fighters still make up a disproportionately high percentage of boxers). Yet in the mid-1970s Sylvester Stallone offered his character Rocky Balboa – nicknamed the Italian Stallion. This character, the epilogue asserts, is an “archetype” of determination for Italian-Americans to look up to. Rocky Balboa is not only an archetype of fierce determination to achieve, however; he is also a racist one. The Rocky archetype does not so much look back to a time when Italian-Americans were looking for acceptance in a racist society, but it begins in the 1970s, a time when they have long been accepted, and looks forward to a moment when Rocky Balboa, the white hero, eliminates the cultural Other. (From Rocky I to Rocky V the “villains” are Apollo Creed [twice], Clubber Lang, Ivan Drago, and George Washington Duke: an African-American, another African-American, a Soviet, and yet another African-American respectively.) The title, Italian Stallions, thus, unfortunately connotes the idea of the “Great White Hope,” which, in turn, connotes the idea of white supremacy. By bringing together articles that show a time when boxing was respected as an honest trade, a time that few casual boxing fans today know much about, a time when boxers could accept losses and keep being professionals both in and out of the ring, Hauser and Brunt have done a great service not only for us readers but also for the boxers described in the pages of Sport who come across not like Rocky Balboa but like the philosopher-fighters found in the pages of W.C. Heinz’s The Professional.

|

|

|

| Upcoming Fights | Current Champions | Boxing Journal | CBZ Encyclopedia | News | Home |