Slow train

coming: Sandy Saddler and the long road to acceptance

By Mike Casey

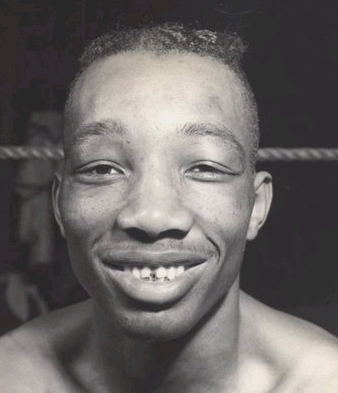

It is virtually certain that Joe ‘Sandy’ Saddler was too worldly

and intelligent a man to expect the boxing world to come and pay him homage when

he concluded his wonderful career.

Saddler had long been aware of the general perception of him. He

was the ugly duckling of the game, the powerful and sometimes ungainly brute who

gatecrashed the party and kicked sand in everyone’s face. His formidable ring

achievements were too graphically emphatic to ever be denied, but they were

greeted with that strangely muted reaction that comes from grudging admiration.

His face didn’t fit, his style didn’t obligingly slot into any one category.

Saddler, the tall and almost skeletal man from Boston, had won in

all parts of the world and defeated the champions of seven different countries.

As well as campaigning in his homeland, his tireless pursuit of the

featherweight championship took him to Cuba, Panama, the Philippines, Paraguay,

Uruguay, Chile, Venezuela and Argentina. Sandy had beaten the great Willie Pep

in three of their four epic meetings and notched 145 wins in 163 fights. Yet

charisma and popularity, those two most precious and winning of attributes, had

never wrapped their arms around Sandy and carried him to the hearts of the

boxing fraternity.

The fans preferred to talk about the phenomenon that was Sugar

Ray Robinson or the perpetual punching machine that was Henry Armstrong. Sugar

Ray could do it all and had everyone in raptures. Young and old people alike

couldn’t say enough about the Harlem Flash, who possessed gifts that were not

normally accorded to mere mortals. Old timers from the era of the great Joe Gans

were hailing Robinson as the most complete and sensational fighter who had ever

graced the stage.

The fans loved Armstrong because they have always loved a fighter

who keeps punching to the end. Homicide Hank was a tornado of a man who could

blow everything from his path on his best night. Like Sugar Ray, Armstrong was

easy on the eye and a thrilling jolt to the heart. When Henry was through, he

had 100 knockouts on his slate and everybody loved to talk about that magical

figure. They didn’t talk too much about Sandy Saddler’s 103.

But then Sandy wasn’t easy on the eye and was rarely thrilling.

He was just a rock hard man with all the necessary tools who got the job done

anyway he had to. If he couldn’t knock out opponents with the fists that carried

power in equal abundance, he would outscore and out-hustle them with skill and

cunning. He had other weapons in his well stocked armoury too, straight from the

Harry Greb box of tricks. A fight to Saddler was a battle of survival in which a

man needed every edge he could get for himself. If that meant a spot of

wrestling and thumbing, not to mention the occasional back-hander, so be it.

Everything about Sandy looked tough and hard. Towering and lean,

his skin was stretched taut over his frame like latex. He often resembled a bird

of prey when he was on the hunt, hovering menacingly as he assessed his target

before swooping with the next two-fisted attack. To the hurt and reeling

opponent under fire, Saddler must have seemed all arms and gloves, all elbows

and sharp bones.

As if to confirm his role as boxing’s villainous misfit, fate

decreed that Sandy’s greatest opponent would be the sublime boxer of the age in

Willie Pep, the genius who made world class men look inadequate with his innate

and unmatchable skills. Pep breezed past them all until he stumbled into

Saddler’s quirky minefield.

Starting blocks

Saddler got out of the starting blocks fast when he turned

professional just before his eighteenth birthday in 1944, fighting frequently

and quickly establishing himself as a comer. His character was tested in only

his second fight, when he suffered the lone knockout of his career to the

dangerous Jock Leslie. Sandy was counted out in the third round at the Hartford

Auditorium in Connecticut, yet there was no period of recuperation or

re-assessment. He was plying his trade in what was arguably boxing’s most

competitive era, when young prospects looking to get a foothold on the ladder

simply couldn’t afford the luxury of long layoffs and self-analysis. It seems

incredible to us now that Saddler packed twenty-two fights into his first

professional year after starting in March. He went 20-2 with a third round

knockout of Midget Mayo on December 26 and was on his way.

In 1946, Saddler dropped a ten rounds decision to former NBA

champion Phil Terranova, but then Sandy began to claim some significant scalps

as he moved inexorably towards his celebrated quartet of fights with Pep.

Travelling down to New Orleans, Saddler stopped future lightweight champ Joe

Brown in three rounds. He fought a draw with Jimmy Carter and then decisioned

Orlando Zulueta at the Sports Palace in Havana.

Sandy

suffered a points reverse to Chico Rosa in Honolulu, but came into his first

fight with Pep on the back of three successive knockouts over Kid Zefine,

Aquilino Allen and Willie Roache. As he prepared for Pep, Saddler had a shrewd

and valuable ally in his training camp in Archie Moore. The Old Mongoose was

still awaiting his own shot at world championship glory, but had already amassed

a treasure trove of boxing knowledge.

Always frank and fair in his appraisal of other fighters, Archie

didn’t kid Saddler about the toughness of his assignment. Moore acknowledged

that Pep was one of the fastest and cleverest ring mechanics in the game, but

pointed out the oft-forgotten fact of life that the very best are still

beatable. Archie reminded Saddler that he was the one who carried the big punch

and urged him to jump on Willie early and stay on him with intelligent pressure.

Moore sparred with Saddler, handing out tips on the art of slipping and blocking

and always looking for any significant chinks in his friend’s armour that the

wily Pep might exploit.

Sandy was a willing student, having dedicated his life to the

toughest sport of all. He didn’t smoke or drink or place any unnecessary stress

on his body. Even in the ring, he was always looking to protect himself as best

he could and was grateful for Moore’s extensive lessons in how to tuck up under

fire and present the smallest possible target.

Saddler was ready for Pep by the time they climbed into the

Madison Square Garden ring on the night of October 29 1948. Following Archie

Moore’s advice to perfection, Sandy stayed tight to Willie, negating the boxing

master’s need to move and gain sufficient leverage for his famously accurate

punches. The result of that fight stunned the boxing world. Willie Pep, the

great untouchable, was knocked out in the fourth round. Genuinely knocked out.

As Saddler always liked to put it, “I knocked him stoned.”

Nor was the sensational ending a one-punch fluke. Saddler had

served notice of the imminent execution by flooring Pep twice in the third round

before putting him down for the count in the fourth. The damage was there for

all to see on Pep’s face, his right eye closed and his nose bleeding.

My father has often told me of how the result of that fight shot

around the world and induced utter disbelief in many. “It was hard to grasp the

reality of it,” he said. “Pep had only lost once in 135 fights before that, a

streak that hasn’t been equalled since. It seemed that nobody could even get

near him, never mind knock him out. And Willie could punch too. He wasn’t just a

fancy Dan.”

Top

Sandy Saddler was at the top of his game and eager to prove that

he was a worthy champion. Less than a month later, he gave another brutal

exhibition of his power in a non-title match against Tomas Beato at the

Bridgeport Armory. Decking Beato three times in the opening round, Sandy stopped

his man in the second with a nose-breaking left hook.

When Saddler hooked up with Pep again at the Garden in February

1949, the enthusiastic crowd was witness to the final true masterpiece of

Willie’s fabulous career. Sandy’s crowding reaped little reward on that occasion

as Pep boxed beautifully to win a unanimous decision by round scores of 10-5,

9-5-1 and 9-6.

Years later in his retirement, Saddler would talk admiringly of

Pep’s astonishing skills and how he could turn an opponent in the blink of an

eye. Much as he admired Willie, however, Sandy wouldn’t let him go away.

Nineteen months would pass before their rubber match at Yankee Stadium in the

Bronx in September 1950, but Saddler kept himself firmly in Pep’s sights as he

reeled off twenty-four straight wins during that time. Sandy took a points

verdict from Harold Dade, stopped Paddy DeMarco in nine rounds and then annexed

the vacant junior-lightweight title with a split decision over old foe Orlando

Zulueta at the Cleveland Arena.

Saddler made a successful defence by halting Lauro Salas in nine

rounds at the same venue and went on to best Jesse Underwood, Miguel Acevedo,

Johnny Forte and Leroy Willis before renewing his hostilities with Pep.

The third fight with Willie had an unsatisfactory conclusion and

failed to settle the question of who was the better man. Pep retired with a bad

shoulder injury at the end of the seventh round, but had come on strong after

taking a nine count in the third to lead by a good margin on all three

scorecards. But Sandy felt good about the fight and had the air of a man who

knew that the balance of power was swinging his way. He had learned how to beat

Pep and kept digging Willie to the head and body with those meaty shots that

never seemed quite as destructive as they actually were.

Being world champion again didn’t quench Saddler’s thirst for

action. Right to the end, he loved to keep fighting and keep mixing it. Over the

next twelve months, he added another fourteen fights to his swelling record and

retained his junior-lightweight crown with a second round knockout of Diego

Sosa.

Photos

If you enjoy looking through the archives for old fight photos,

then go hunting for the famous picture of Willie Pep after his fourth fight with

Saddler at the Polo Grounds. You will see one of the all-time great shiners, an

absolute peach of a black eye that would have stopped King Kong in his tracks.

Sandy and Willie did just about everything it was legally possible to do in the

foul-filled finale of their memorable series.

It was typical of these tough men that they were never really

able to see what all the fuss was about. Pep never called Saddler a dirty

fighter. Saddler had nothing but praise for Pep’s God-given talent. It just

irked Sandy that he was the target of the critics when the talk turned to dirty

tactics.

Here is how Saddler saw the third and fourth fights with Pep in a

seventies interview with writer, Peter Heller: “The third fight, Pep knew I

could punch. He knew that. When I got on top of Pep, when I started to punch

him, he would grab my arm. I’m trying to pull my arms away so I can punch him.

Now, what was so dirty about that? The man grabbed my arms and I pulled my arms

away so I could punch, and he’s holding the other one and I’m banging with one

hand. I just got right on top of him, just beat him, not unmercifully, but I

just beat him good. Some people say he quit, but I just banged him something

terrible. The fourth fight, he was just in there slipping an ducking until I

caught up with him.”

Like many fighters looking back, Sandy was a little loose with

the truth about these brawls. With both men going at each other hell for

leather, the apportioning of blame was virtually pointless. And Pep was doing a

lot more than slipping and ducking in that fourth fight, even though Saddler’s

heavier artillery finally won the day. Willie’s shiner began to bloom in the

second round, when he sustained a bad cut to the right eye and was floored by a

Saddler left. But Pep rallied superbly before the end of the session, rocking

Sandy with a big right and then pot-shotting him with thirteen unanswered blows.

The fight was a bizarre cocktail of the bad and the beautiful, as

memorable moments of skilful fighting blended with plain old-fashioned bar room

brawling. Twice the men wrestled each other to the canvas, in the sixth and

eighth rounds. Never forgetting the priceless advice he received from Archie

Moore, Sandy kept hustling and bustling Willie, slowly wearing him down with

hurtful shots to the head and body.

By the end of the ninth round, Pep was all in. Slumped forward on

his stool, he seemed to be looking for someone or something to pump fresh oxygen

into his lungs and fresh ambition into his heart. The Polo Grounds began to

rumble with the familiar and knowing sound that precedes a fighter’s imminent

surrender. There were all sorts of things going on. Even Pep’s handlers didn’t

seem to know if Willie was coming out for the tenth, while ructions at ringside

were adding to the general confusion. Saddler’s manager, Jimmy Johnston, was up

on his feet, claiming that judge Artie Aidala was being influenced in his

thinking by Dr Vincent Nardiello, the boxing commission physician.

Then the sideshow was over and the bit players were suddenly

irrelevant. Willie Pep was through. The fight was over and Sandy Saddler was

still the world featherweight champion.

Retirement

Between the last fight with Pep and his retirement from an eye

injury in 1957, the great Sandy Saddler still had the hunger to engage in

twenty-three more contests. He defended his featherweight championship twice

more, unanimously outpointing Teddy ‘Redtop’ Davis at Madison Square Garden and

stopping Flash Elorde in thirteen rounds at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. But

it was an exciting non-title match against big puncher Tommy Collins that

underscored Sandy’s reputation as a danger man who could never be written off.

Rough and tough he might well have been, but Saddler was not a bully who ran for

shelter when the other man starting shelling back.

The fight with Collins took place at the Boston Garden in 1952

and an upset seemed to be in the air when Tommy decked Sandy in the opening

round. Collins shook his man again in the third, but Tommy was one of those

fragile bangers who didn’t possess the steel and know-how that Saddler had

forged over years of tough campaigning. Sandy rolled with the early thunder and

then fired back to floor Collins twice in the fifth to force the referee’s

intervention.

With retirement came the long waiting game for Sandy Saddler. The

wait for acceptance. For better or for worse, Willie Pep had become his strange

partner in marriage. It was Pep who was introduced as one of the great

featherweight champions whenever he stepped up into the ring to take a bow in

guest appearances. It was Saddler who followed him as a polite after thought.

Saddler admitted to feeling bitter about this on more than one

occasion. He liked Pep a lot. The two men remained good friends. It was the Pep

Effect that riled Sandy. It was Saddler’s view that he deserved at least equal

ranking with his old adversary. Pep’s supporters always countered with the same

argument: the plane crash argument.

In January 1947, Willie had suffered serious injuries in an

airplane crash, so much so that his boxing career appeared to be over. That was

nineteen months before his first fight with Saddler and many contend that Pep

was never quite the same brilliant fighter from that point on.

True? The question is near impossible to answer in his case. With

most boxers, we would pose the question, “Was he still as good?” Willie was so

outrageously exceptional that we need to ask, “Was he still as brilliant?”

Was Sandy Saddler the better man with his 3-1 advantage in those

four fights? Which Willie Pep did he beat? Whose achievements were greater over

the span of their long and outstanding careers?

Unfortunately, the questions keep coming when we attempt to rank

the titans of the game in an all-time perspective. Fighting Harada twice

defeated Eder Jofre at the peak of their respective powers, but was Harada the

superior bantamweight? Most would surely refute that suggestion.

It sometimes takes decades for the accomplishments of great

fighters to be absorbed and properly judged. Wherever Sandy Saddler stands in

the pantheon of great featherweights, the one sure fact is that his star

continues to slowly rise with the passage of time. The International Boxing

Research Organization (IBRO) recently voted Willie Pep the greatest of all

featherweights, but there was Saddler suddenly at number two: sneaking up and

still pursuing Willie with all his old, devilish verve.

Maybe these two wonderful giants of the ring aren’t finished with

each other yet!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|