The

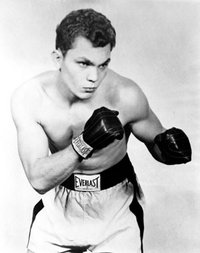

travels of Charley O’Brien: a.k.a. Carlos Ortiz

By Mike Casey

It was a landslide. There was no room for complaints, no

opportunity to lambast the referee and judges for being blind, incompetent or

downright crooked. The scorecards had been announced and they were enough to

make even a worldly old pro wince with embarrassment. Referee Frankie Van scored

the fight 74-60. Judge Bud Trayner tabbed it 74-58 and Dave Zeno completed the

set with a tally of 74-66.

It was the night that Old Bones Joe Brown finally turned into the

tortoise that got whipped by the hare. After a six-year reign and eleven

defences of his lightweight championship, Joe had been bumped emphatically off

his throne by the dashing young prince of Puerto Rico. It was the twenty-first

day of April in 1962.

Carlos Ortiz had travelled to the Convention Center Las Vegas for

the hardest fight of his life and ended up strolling past one of the greats of

the game at a canter. Now Carlos was in his dressing room, bursting with that

strange mix of joy and magnanimity that comes with the adrenaline rush of

winning.

“Joe is not the same fighter of two, three or four years ago when

I was coming up, but he deserves a return bout. He is a great fighter and was a

very good champion.”

There was no return because Joe Brown was suddenly old and could

no longer win the big ones. He would drop a decision to Luis Molina in his next

fight and later get knocked out by Dave Charnley, the tough Englishman he had

frustrated and vanquished in two title defences.

While Joe’s old bones would continue to creak, young Carlos Ortiz

would prove a worthy successor as one of history’s greatest lightweights. The

twenty-five year old stylist possessed a shrewd boxing brain, an excellent jab,

a good range of skills and solid punching power. In his full pomp, he would come

to be a commanding ring general.

Ortiz had one other vital component in his armoury, an essential

quality that is so often misunderstood and misused: Arrogance. That important

ingredient has to be brewed and fermented to exactly the right measure. It must

co-exist in harmony with self-discipline and sober judgement.

After beating Joe Brown, Carlos claimed he knew he was going to

win from as early as the first round. If that was the case, then the cool and

intelligent challenger never gave the game away. He befuddled Joe all night long

with fast and accurate jabbing, never allowing the champion to set himself and

unloose his heavy artillery. When Joe tried some old tricks, Carlos kept a rein

on his temper and stuck to his game plan.

“Joe hit me after the bell in the sixth round,” Ortiz would

recall. “I told myself, ‘Don’t get mad now’.” Both fighters slugged away at each

other beyond the bell as referee Frankie Van tried to prise them apart. With a

mountain to climb, Brown simply couldn’t find a way to trap and slow Carlos.

Bleeding from a cut to his left eye from the challenger’s damaging jab, Joe was

virtually shut out of the fight and acknowledged as much. “I just couldn’t get

off the ground. I think the real Joe Brown could whip Carlos Ortiz. But Carlos

was smarter tonight than I thought he was.”

Ortiz had won and he had won the smart way. “When I was a kid,”

Carlos said, “I read about how Billy Conn had Joe Louis beaten, only to get too

cocky and get flattened. But not me, I told myself. Box and win. That is just

what I did in the Brown fight.”

Fear

Carlos Ortiz was always smart, a man with a plan who had total

faith in his ability to reach his destination. He knew fear like any other

fighter, but constantly challenged that most formidable of emotions by meeting

it square on. He wasn’t supposed to beat Joe Brown, any more than he was

supposed to have beaten the dangerous Len Matthews three years earlier.

Matthews, the experts said, would demolish Ortiz. Len was a big favourite to win

that fight before his hometown fans in Philadelphia. Ortiz stopped him in six

rounds.

Globetrotting Carlos grew accustomed to being told that he would

come unstuck if he kept wandering into other people’s back yards. Yet he went to

London to beat Dave Charnley and Maurice Cullen, travelled to Manila to see off

Arthur Persley and Flash Elorde, and trekked to Japan to take care of Kazuo

Takayama and Teruo Kosaka. Ortiz earned a draw with fellow great Nicolino Locche

in Argentina and turned back the challenge of Sugar Ramos in the intimidating

cauldron of the El Toreo Bull Ring in Mexico City.

Ortiz knew what it was like to move around. When he was six years

old, his family uprooted from Puerto Rico and moved to New York. The transition

was tough and not immediately successful for Carlos. He described himself as ‘a

bad kid’ who gave his parents plenty to worry about. But Gotham was soon in the

blood of Ortiz. Like Emile Griffith, who migrated from the Virgin Islands,

Carlos would steep himself in the great city and become a big crowd favourite at

Madison Square Garden in the golden years to come. Not that he was ever allowed

to get too full of himself. To his colleagues in the famous and predominately

Irish task force of the Fighting Sixty-Ninth of New York, where he served as a

sergeant, Carlos continued to be known as ‘Charley O’Brien’.

Ortiz knew the value of a dollar and the good sense of

straightening himself out and finding a purpose in life. After becoming world

champion, he recalled the early days: “My old man made less than ninety dollars

a month. Do you wonder, then, why I sock my money way? I was a bad kid who gave

my parents trouble both in Puerto Rico and in New York, but I got over that

after I joined the Police Athletic League and took up boxing. Today I’m better

adjusted to my better surroundings and home in the Bronx. We don’t squander our

money, but we live according to our means.”

Ortiz made rapid progress after joining the Police Athletic

League under the guidance of his first manager, Ed Ferguson. By 1953, Carlos was

a member of the Boys Club team and won his first 135lb international

championship in London. He quickly added the Metropolitan AAU title to his

collection and was sailing along very pleasantly with no thoughts of turning

professional. How a generation of lightweights must have wished that he had

remained among the Simon Pures.

Ortiz’s limited amateur experience didn’t stop him from making

fast progress up the pro rankings. He matured quickly into a clever and adept

fighter, strong and capable in most departments of the game. He could box, punch

and defend himself ably when the game plan called for greater caution against

the division’s superior hitters.

Carlos was unbeaten in his first 27 pro fights, finally tasting

defeat when he dropped a split decision to Johnny Busso at Madison Square Garden

in the summer of 1958. Ortiz avenged that loss just three months later, before

travelling to the old Harringay Arena in London to upset the rugged Dave

Charnley by decision. A great southpaw and a very hurtful puncher, Charnley

would go on to lose a hotly disputed decision to Joe Brown in the Ring

magazine’s fight of the year of 1961.

My father once told me of a promising young amateur from that era

who was eager to turn pro and figured it would be a good idea to test the water

by sparring with Charnley. The experience was a rude awakening for the amateur

man. He said he couldn’t recall being banged in the body so hard and very

quickly revised his career plans. These were the top class men that Carlos Ortiz

was starting to beat. But he would be frustrated by a couple of other tough pros

before earning his championship stripes.

Kenny Lane and

Duilio Loi

There was never the best of blood between Ortiz and that feisty

little man from Muskegon, Michigan, Kenny Lane. When Carlos went down to Miami

Beach in December, 1958, he wasn’t at all happy about what transpired. Lane

walked off with a majority decision and Carlos believed he had been gypped. He

was ready for Kenny when the two men were re-matched six months later for the

vacant junior-welterweight crown at Madison Square Garden.

Lane couldn’t get through two rounds as Ortiz went to work in

coldly determined fashion. Carlos decked Kenny in the opening round and didn’t

let up in the second. Ortiz caught Lane with a peach of a right to the eye,

opening such a serious cut that the doctor had to stop the contest. Carlos would

describe that punch as the hardest right hand he had thrown since turning

professional.

At that time, however, the junior-welterweight crown was not a

greatly prized bauble, and Ortiz regarded the victory as little more than a

stepping stone to the lightweight championship. He wanted Old Bones before Old

Bones got too old, but tricky business in the junior-welterweight class would

keep Carlos tied up for almost another two years. The man mostly responsible for

the delay was the outstanding Italian, Duilio Loi.

Carlos defended his title against Loi at the Cow Palace in San

Francisco in June 1960, winning a split decision in the first of a trilogy

between the two modern greats. It would mark the only time that Ortiz would beat

the brilliant Italian, who would lose just three of his 126 professional fights.

Their second match in the noisy furnace of the famous San Siro

Stadium in Milan also split the three officials, with Loi getting the nod. Fans

of both fighters were equally divided on who won these closely contested

battles. In San Francisco, Carlos had won with the help of a knockdown that many

considered to be a slip, although he was the stronger man in the home stretch.

At the San Siro, before a massive pro-Loi crowd of 65,000, it was

the Italian who came on in the closing stages. Duilio fought a shrewd battle

throughout, confusing Ortiz by cleverly switching tactics as the fight

progressed. Loi was very much the canny counter puncher in the early rounds as

Carlos pressed the action. After eight rounds, Ortiz seemed to be on his way to

victory as Duilio began to slow.

With the crowd urging on their hero, Loi found his second wind

and assumed the role of attacker as he scored repeatedly with hard body punches

to have Carlos tucking up and retreating. The Italian was coming off better in

the quality exchanges and showing his full range of deft skills as he bobbed and

weaved under the champion’s blows and found the mark with accurate jabs and

hooks. When Carlos fired back, Loi took many of the punches on his arms and

gloves.

Ortiz never stopped firing in his efforts to turn the fight

around, but the battle was lost and so was his junior-welterweight crown. Carlos

returned to the San Siro for the rubber match with Loi in June 1961, but came up

short again as the Italian fox won unanimously. A proud man, Ortiz felt bad

about the two defeats and continued to question who was really the better

fighter. The silver lining in his black cloud was that he was free to go back to

the vastly more respected lightweight division and realise his great dream. He

hammered out a pair of decisions over top contenders Doug Vaillant and Paolo

Rosi and then went to Vegas to take down Joe Brown.

Champion!

Ortiz couldn’t crow loud enough after beating Old Bones. “I beat

Brown because I was in the finest physical condition of my life,” said Carlos.

“I won the title because I went after him right from the start and at once

proved to him that the only way he could retain the championship was to knock me

out. I trained for the toughest fight of my career. It turned out to be the

easiest. I want to prove that I am a fighting champion. I can adjust my style to

offset that of any opponent.”

In the years ahead, Carlos would prove both points in style as

the confidence of being a world champion enabled him to raise his impressive

game to a new level. Challengers would never have to come looking for Ortiz. He

was more than happy to pay them a visit. But New York and Puerto Rico would

still get their share of the champion between his treks to other boxing nations.

After making his first successful title defence with a fifth

round knockout of Teruo Kosaka in Tokyo, Carlos returned to his roots when he

gave former foe Doug Vaillant a title tilt at the Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San

Juan in April 1963. Twenty thousand fans came to see Carlos give a commanding

and dazzling performance. He made a big statement of intent in the opening

minute of the battle when he knocked Vaillant down with a left hook. Doug was a

courageous and determined challenger and fought back furiously for the remainder

of the round. He kept in the fight through the first five heats, but it was

Carlos who was scoring with the more authoritative punches.

Carlos forged ahead, but Vaillant never stopped trying. Doug made

a big effort to sway things his way in the tenth as he winged shots to the body

of Ortiz. But Vaillant’s desperation showed as the fight wore on and Ortiz kept

up his steady pressure. Referee James J Braddock, the old heavyweight champ,

issued five warnings to Doug for low punching and took away a point for butting.

Everything was going the champion’s way by the eleventh. Carlos

was employing his jab beautifully and with telling effect. He was also besting

Doug on the inside with some lusty body punching. When Ortiz came out for the

twelfth, he knew his man was ripe for the taking. Carlos charged from his corner

and pounded Vaillant with body blows, decking the challenger twice and nearly

knocking him out before the bell. Vaillant tottered back to his stool on

unsteady legs, a man buying himself a mere minute of respite before his

execution. He was down twice more in the thirteenth and being pummelled against

the ropes when referee Braddock rescued him.

The big crowds continued to turn out wherever Carlos Ortiz

journeyed. He was a national hero who waged war with other national heroes

before screaming crowds in vast stadiums. The atmosphere was rarely anything

less than electric at an Ortiz fight. When Carlos made the first of two defences

against junior-lightweight champ Flash Elorde at the Rizal Memorial Coliseum in

Manila in February 1964, the champion was also taking on a partisan crowd of

60,000. Many top class fighters have wilted and withered under that kind of

pressure. Not Ortiz.

Calm and collected as ever, Carlos ignored a gash to his right

eye in the second round and dealt with everything the game and talented Elorde

could dish out. A clever and exciting fighter, Flash looked a lively and

dangerous challenger in the early going as he counter punched skilfully and

navigated his way around Ortiz’s jab by ducking and weaving and rifling the

champion with solid combinations to head and body.

But Carlos had reached that wonderful point in his prime where he

seemed to know that he couldn’t be taken. He began to slow Elorde with some

vicious uppercuts to the body in the fifth round, piling up valuable points

thereafter and carving out a good lead. Flash was unable to close the widening

chasm and his spirited rally in the thirteenth round proved to be his last throw

of the dice.

There was always a noticeable little jig in Ortiz’s step when he

knew he was close to closing the show, and he sprang from his corner at the

beginning of the fourteenth to finish the job. He drove Elorde to the ropes with

a series of powerful blows and was battering the challenger with big lefts and

rights when referee James Wilson stopped the fight. Flash, courageous as ever,

was still fighting back and protested Wilson’s decision. “I had to stop the

fight or he would have killed you,” Wilson replied.

A Whip!

“The kid was fast, real fast - he was a whip!” So said Ortiz of

the new kid in town, Panama’s flashy and impressive Ismael Laguna. Carlos made

that discovery to his considerable cost. When he changed back into his street

clothes and departed the Estadio Nacional in Panama City in October 1965, Ortiz

was no longer wearing his crown. The young whip had whipped him in the climax to

a seemingly endless nightmare.

Carlos and Panama City just didn’t go together. Ortiz didn’t like

the food and then the local water gave him a bad attack of diarrhoea. The fight

was postponed for a month and the extra time didn’t improve the defending

champion’s chances.

Carlos was still unwell and nowhere near the weight limit on the

eve of the fight. A long session in a steam bath resolved that problem, but he

was too weak mentally for the lithe and ambitious Laguna. By his own admission,

Ortiz simply couldn’t cope with the challenger’s incredible speed of hand and

foot. The decision and the lightweight championship went to Panama.

It was a different story seven months later when Carlos regained

the title by scoring a unanimous points victory over Ismael in San Juan. But the

greatly talented Laguna was far from finished as a major player and would come

back to haunt Ortiz nearly two years later in the best of their three fights at

Madison Square Garden.

Carlos had his share of adventures on the way to that one. In a

bizarre title defence against former featherweight champion Sugar Ramos in

Mexico City, Ortiz became the innocent victim of incredible circumstances. The

Mexican supporters erupted when their man Sugar floored Carlos in the second

round, but their joy turned to despair and derision when referee and former

light-heavyweight king Billy Conn stopped the fight in Ortiz’s favour in the

fifth after Ramos had sustained a cut eye.

The World Boxing Council (WBC) wasn’t at all pleased. It ruled

that Conn had stopped the bout improperly and had given Ortiz the benefit of a

long count in the second round. In the days of only two controlling bodies in

the sport (and most of us thought that was two too many), Carlos was stripped of

his WBC title and left with the recognition of only the World Boxing

Association, the Ring magazine and almost everyone else on the planet.

If these events bothered Ortiz, he was too professional to allow

them to affect his ring performances. It is true to say that he hadn’t been in

top form against Ramos, but Carlos would respond by going on the roll of his

career over his next three fights. He successfully defended his WBA crown with

another fourteenth round stoppage of Flash Elorde at Madison Square Garden, and

then blasted Ramos to defeat in the fourth of their eagerly awaited rematch in

San Juan. The challengers were being steadily picked off and sent packing. Even

Kenny Lane got another chance and was unanimously outpointed. Now Carlos could

turn his attention to Ismael Laguna again. And Laguna and his army of fans were

coming to Shea Stadium.

The last

defence

The atmosphere crackled at Shea on the Wednesday night of August

16, 1967 when Ortiz and Laguna entered the ring. Puerto Rican and Panamanian

flags waved among the crowd of 18,000 fans as they anticipated a very special

match-up. The odds were even, Laguna having blossomed into a much more mature

and rounded fighter since his defeat to Carlos in Puerto Rico. The challenger

had compiled a 7-1 score since that match, a points loss to Flash Elorde being

more than compensated for by quality wins over contenders Carlos Hernandez,

Percy Hayles, Daniel Guanin, Frankie Narvaez and Alfredo Urbina.

Ortiz was a champion at the top of his game and eager to

underline his superiority over the panther-like youngster who had dazzled him in

the heat of Panama City. Carlos did so magnificently, finding the range early

and nailing Laguna with beautifully accurate shots all the way through. The

champion marked his territory in the second round when he staggered Ismael with

a powerful left-right combination to the jaw. It seemed that Ortiz hit the

jackpot every time he threw the right. He forced Laguna’s knees to dip with a

big shot in the fourth and cracked the challenger on the jaw with another peach

of a blow in the eighth.

What was now noticeable, however, was that Carlos was having to

pace himself more carefully as he approached his thirty-first birthday. Having

gained the upper hand, he allowed Laguna back into the fight in the middle

rounds as the spirited challenger let fly with his impressive repertoire of

punches. The Panamanian fans grew increasingly excited as it appeared that their

man was coming on strong and heading back to the top of the tree.

But quality champions always have quality moves in reserve.

Sensing the danger, Ortiz came to life again in the tenth round and re-employed

his damaging right cross to regain control of the fight. He jolted Ismael in

that round and again in the eleventh, and the challenger’s best rallies could

not offset the champion’s skill and guile in the home stretch. The decision was

unanimous for Carlos, by scores of 10-4-1, 10-4-1 and 11-3-1.

Ortiz had made the last successful defence of his crown. His

desire waning, he would lay off for ten months before losing his title to Carlos

(Teo) Cruz on a tight decision in the Dominican Republic. There would be other

battles for Carlos thereafter, but of far less significance. A ten-fight winning

streak that began in 1969 was eventually snapped by a sad and meek surrender to

Ken Buchanan in 1972.

But the important work had been done. Charley O’Brien had put his

numbers on the board and established himself as one of the great lightweights.

Like good wine, he travelled well.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|