Fearless: When Owen

Moran thrilled America

By Mike Casey

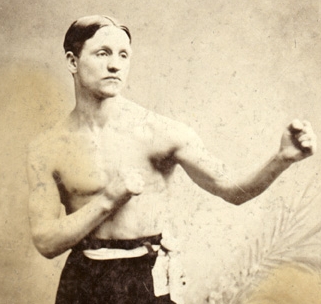

The face stares out of the picture taken long ago, like that of

an old gunfighter. The eyes are the most striking feature, baleful and quietly

menacing as Owen Moran seems to challenge the camera to penetrate the shield of

his tough countenance and guess his thoughts and innermost secrets. The dark

hair that frames his face is defiant in itself, slightly dishevelled as it

tumbles from his crown and flops casually across his forehead.

There is something haunting and oddly captivating about the less

sophisticated photographs of the early twentieth century. People so often look

like the living dead as their eyes meet yours and suck you into their fading and

mysterious world. One instinctively looks for Boris Karloff in every family

portrait. In a photographic studio of today, of course, the folks of that age

would look no more mystical or threatening than you or I.

However, there are exceptions to every rule, and I would

confidently wager that Owen Moran would look pretty much the same if he were

able to step into a time machine and rejoin us now. For Moran was an exceptional

human being and a true fighting man from head to foot. It helped to look like

Owen did when you were plying your trade against men of the ilk of Abe Attell,

Harlem Tommy Murphy, Ad Wolgast, Battling Nelson, Jim Driscoll and Packey

McFarland.

People always commented on how hard Moran looked. They remarked

constantly on his seriousness and intensity. But one word came up more than any

other whenever the formidable Englishman was in the heat of battle: fearless.

Deceive

The written word, however well woven, can still deceive. Write

about any tough guy from Moran’s stormy and anarchic era, and it is difficult to

avoid the implication that he was a sullen, mean and thoroughly unapproachable

individual. For many, the enduring appeal of Stanley Ketchel is that he was a

psychotic powder keg that could go off at any moment.

But the truth is invariably more complex and far less dramatic.

Owen Moran always staggered people on the rare occasions he cracked a smile, yet

he was never anything less than a charming and sociable man to those who treated

him fairly. But fighting was his trade and his life and could not, in his view,

accommodate levity or benevolence. Owen, like so many of his contemporaries,

simply had to be good at what he did and thoroughly committed. The simple

alternative was a grinding life of anonymity in the harsh and unforgiving

England of his time. Moran was a West Midlander from the city of Birmingham, or

a ‘Brummie’ to his fellow countrymen. He could just as well have hailed from

London, Liverpool, Manchester or Newcastle, where it was no less of an uphill

task for a working class man to escape a grim and repetitive existence.

Owen wasn’t a big man and only spoke when he felt the need to.

There was nothing gregarious about his nature. His statements of intent were

delivered confidently and plainly. Like a miniature Clint Eastwood, he reminded

one of that chilling old saying, “It’s always the quiet ones.”

Not that Moran was incapable of erupting if he felt he had been

wronged. Promoter Jimmy Johnston saw the dark side of Owen when the two men had

a difference of opinion during a meeting in Johnston’s office. The disagreement

quickly escalated into a heated argument and climaxed with Moran throwing

himself at Johnston with both fists swinging.

The size and reputation of an opponent never bothered Owen Moran

inside or outside the ring. A natural bantamweight, he quickly tired of his

weight class after winning the English version of the bantamweight championship

by outpointing Al Delmont at the National Sporting Club in London. Moran wanted

to hunt bigger game and began to attack the world’s best featherweights and

lightweights. He loved to fight and he wanted to fight the best men available.

In common with Jimmy Wilde and so many other fighters of that tough era, Owen

cultivated his skills and his hard attitude in the rough and tumble arena of the

boxing booths.

He captured the attention of Captain H.E. Cleveland, a famous

boxing critic of the time, who saw Moran at work in Professor Harry Cullis’

booth. There was special aura about the laconic youngster, whose cyclonic style

of fighting was tempered by wonderfully subtle cleverness.

For Owen Moran was indeed something of a technical paradox. He

could attack and defend equally well and vary his tactics according to the task

at hand. He loved nothing more than to scrap with a known scrapper, yet derived

equal pleasure from outmanoeuvring a cunning fox.

Much like Roberto Duran in later years, Owen’s explosive, sudden

rushes would often serve as a canny cloak for his precision punching and

defensive skills.

Owen Moran had his first fight in America in 1907 and remained

there for just over six years, during which time Uncle Sam couldn’t get enough

of him. How good was the grimly determined little battler from Birmingham? After

outclassing Frankie Neil in his Stateside debut at the Dreamland Pavilion in San

Francisco, Moran was being likened to none other than the genius of the age: Joe

Gans.

Champion

Before the Neil fight, Moran was aware that he had to sell

himself to the American public, even though bragging never seemed to sit well

with him. He kept it short and sweet as always. “I’ll show the people of this

country that the country where I come from will be able to send over one

champion.”

Frankie Neil was a dead game San Franciscan battler who never

stopped attacking and probably had more courage than was good for him. Just a

year before, he had fought with typical courage in an unsuccessful bid for Abe

Attell’s featherweight crown, taking Abe all the way to a 20-rounds decision.

Against Moran, Frankie found himself hitting shadows and

apparently getting hit by a hammer. Despite trying with everything he had, Neil

simply couldn’t find a way past the technical brilliance of the English wizard.

Owen put forth a memorable exhibition of skilful boxing and commanding power as

he captivated and impressed the West Coast crowd. The scouting reports on Moran

had filtered through in the run-up to the fight. Reports from the East and

regular updates from the Moran camp had spoken glowingly of the tough and

exceptionally talented man who was about to mark his territory. But the

wonderful reality far surpassed the expectations.

Ringside reporter Eddie Smith wrote of Owen: “He proved to be the

greatest find of many years, and his clean-cut clever style of milling will live

in the memory of the lucky fans who witnessed last night’s contest for many days

to come.”

Moran demonstrated that he could hit with great timing and

precision with either hand. Beautifully balanced, he made so few mistakes that

reporter Smith paid him the highest possible compliment by comparing his

artistry to that of lightweight genius Joe Gans.

Frankie Neil won the admiration of the crowd at the Dreamland

Pavilion for his enormous courage and willingness. Never once did he stop

charging and ploughing forward, ever searching for the formula that would make

the ghost before him turn into mortal flesh and blood. But Moran had Frankie’s

number from the opening gong and never once looked like being toppled from his

pedestal.

The intrigue of the battle was the strange marriage of Moran’s

skill and Neil’s never-say-die pluckiness. Frankie took a sustained and painful

beating, yet kept rushing Owen in frantic bids to land a significant blow and

slow the Englishman’s march.

The bout got underway at seven minutes before ten and the opening

round offered the first hint of Neil’s fate. The crowd was eerily silent as the

two men initially felt each other out and showed some artful and clever

feinting. Then Frankie made his move and discovered that Moran was infinitely

more than just a nice boxer. Neil attempted a left to the body that fell short

of the target and brought him to close quarters with Owen. The first significant

action erupted suddenly as the two men teed off in a fast and vicious exchange.

But one blow sounded above all the others. With an incredibly loud thud, Moran

connected with a left hook to the jaw and followed up with a similar blow of

equal force.

Neil took the punches remarkably well, but the warning signs

continued to pop up on his bumpy road. What shocked the locals, who had grown

accustomed to seeing their Frankie out-fight many bigger opponents at close

range, was how superior Moran proved to be at the infighting.

Students of the game who were seeing Owen for the first time

found him a fascinating case study. The English ace would only fire his punches

when confident that he could hit the target, but his agile mind was no less

evident as he studied Neil’s every move. What could Frankie do? He very quickly

made the heart-dropping discovery that he could neither outbox nor out-slug

Moran.

It appeared that the contest would be over as early as the second

round, when Moran opened up in earnest and hammered Neil repeatedly with left

hooks to the body and right crosses to the jaw. Paving the way for these blows

was an educated and stunningly effective left jab that snapped to the target

with great force from only a short distance.

Neil took his punishment and continued to rush Moran, but the

only morbid intrigue of the one-sided battle was how long Frankie could last. It

seemed he would go under in the sixth round as he wavered and shook from Moran’s

precise jabbing and superb counters. Then Neil was suddenly down from a right

cross to the jaw and apparently out to the world. But he somehow struggled up at

nine and brought applause from the crowd as he bulled Owen to the ropes.

However, Neil’s increasing desperation was shredding his ability

to think and plan correctly. He was hooking and swinging almost exclusively with

his left hand and Moran was easily able to anticipate Frankie’s ill-timed rushes

and predictable home run slashes.

The beating administered by Moran became more brutal as the bout

wore on, to the distaste of many reporters who felt that Neil should be saved

from further punishment. Referee Billy Roche felt that his hands were tied on

that matter, revealing later that Frankie’s father had assumed responsibility

for his son’s welfare and had urged Roche not to halt the proceedings.

That didn’t cut too much ice with Captain Duke of the local

police, whose men were clambering into the ring in the sixteenth round just as

Neil’s seconds finally threw in the sponge.

Moran received a tremendous ovation from the crowd and paid

Frankie tribute when addressing reporters. “I asked referee Roche to stop the

fight two rounds before the end came. I realised that I had Neil at my mercy and

did not want to see such a game little fighter get an unnecessary beating. I

believe I fought the greatest battle of my career. I want to take on Abe Attell

next. If I beat him, I will demonstrate to the world that I am the greatest

living boxer at my weight.”

Abe Attell

On January 1, 1908, at the Coffroth’s Arena in the great old

fight town of Colma, Owen Moran got his chance when he fought the first of his

five battles with fellow maestro, Abe Attell.

The two little titans were well matched, to the extent that

referee and former heavyweight champ James J Jeffries was unable to decide a

winner after 25 rounds of clever and hard- hitting duelling. So aligned were

Moran and Attell in pure talent that one could barely slip a cigarette paper

between them.

While Owen had played a wait-and-bait game for much of his

contest with Frankie Neill, the game plan against the artful and cagey Attell

required more urgency. Moran knew that he couldn’t afford to lay back. Much as

the American public had quickly grown to adore him, he would learn that the more

hardened officials of the game would do him no favours against their own.

Owen willingly took the role of the aggressor against Abe,

pursuing the champion constantly and aggressively but always with great speed

and deft skills. Attell, in turn, needed all of his tricks to bank the fire and

keep his distance.

Abe’s punches lacked their normal snap and authority as Moran

blunted their effect with his skilful and evasive form of aggression. But Attell

was a wonderful fighter who could still leave his mark when under pressure. He

found the range sufficiently to give Owen a black eye and a bleeding nose.

Moran clearly relished the examination paper that had been set.

Abe was no less adept than the Englishman at feinting and slipping and was just

as much of a tough cookie at taking his medicine. He avoided many of Moran’s

hooks and swings to the jaw and didn’t appear greatly hurt by the body blows

that were ripping into his stomach.

It was apparent that the two chess masters were cancelling each

other out, but the crowd of some 8,000 found the battle of wits constantly

engrossing. Moran switched between orthodox and southpaw to get close to Attell,

following up with fast and hard blows on the inside. Abe jabbed and countered

and hustled as each man searched for a weakness in the other’s game.

The twenty-fifth and final round saw Owen making a grandstand

charge to grab the fight and the decision. Keeping his head down, he sailed into

the champion with a volley of lefts and rights as Abe hit back in a thrilling

finish. The fighters continued to tear at each other after the bell, and referee

Jeffries needed much of his famous muscle to separate them. Jeff would tell

reporters that he found it impossible to name a winner after such a close and

intensely fought battle.

Attell would continue to frustrate Moran. Owen could equal and

sometimes better Abe in combat, but could never conclusively or officially

master the man they called the Little Hebrew. The two men would fight three

further draws, while Attell would capture the newspaper verdict on two other

occasions.

Battling

Nelson

It is hard to believe that Owen Moran never added the

featherweight or lightweight championship to his roll of honour. He truly was

the nearly man who was as good as anybody on his day but never quite got the

essential breaks. His progress was checked repeatedly by draw decisions and

highly questionable defeats.

Only the unbiased boxing observers of the day knew the truth of

some of these affairs, and there was certainly no doubt in the mind of the

esteemed Nat Fleischer that Moran belonged with the all-time elite. In Nat’s

view, Owen was the third greatest lightweight behind the dynamic duo of Joe Gans

and Benny Leonard.

It was in that weight division, one of boxing’s most

talent-laden, that Moran would make his indelible mark. On November 26, 1910, at

Blot’s Arena in San Francisco, he did what no other man could ever do: knock out

the great Durable Dane, Battling Nelson. Eddie Sterns had stopped the young

Nelson and Ad Wolgast had butchered Bat to a standstill in their titanic

engagement at Port Richmond. But nobody had put Nelson down for the count. It

seemed that boxing would never see that particular curtain fall.

The execution was painfully drawn out as Moran’s clever attacks

were heroically met by Nelson’s almost inhuman resistance. Bat, it seemed,

regarded death as a more honourable exit than even the bravest capitulation. He

was outsmarted and out-manoeuvred from the outset, yet never stopped trying to

smash and batter his way through Owen’s defences.

There was nothing new in Nelson taking a shellacking to earn his

daily bread. He had carved his formidable reputation from his simple but

murderously effective hit-or-be-hit approach. But this time it was different and

the wise birds at ringside sensed it. By the ninth round, Nelson was tiring and

flagging so badly that his backers feared the worst. Yet Moran’s coup-de-grace

in the eleventh round was shocking for all that

It is ever thus with the giants of the game. We see the axe

cutting ever deeper into the tree, yet the inevitable crash still jolts the

system. Nelson was moving in on Moran for the umpteenth time, enjoying limited

success with occasional blows to the body. A left hook to the Englishman’s head

offered Bat greater encouragement, but then he ran into the equivalent of a

flying brick. As the fighters broke from a clinch, Moran ducked in anticipation

of a left swing from Nelson. As Owen rose up, he fired a perfectly timed right

straight from the shoulder that cracked against Bat’s chin with terrific force.

Nelson was bowled over like a skittle as the crowd roared, yet remarkably

scrambled to his feet at the count of nine.

There was no respite for the former lightweight champion as he

was swept into a maelstrom that seemed to whirl and throw him around the ring

for an eternity. He hit the deck five more times, twice being wrestled down as

Owen tried to shake himself free to apply the kill. Finally, Moran found the

killer punch. A right to the head concluded the rough-and-tumble battle, with

Nelson just failing to beat referee Ben Selig’s count. Bat protested as great

fighters do, but ringsiders were relieved that a legend of the sport would not

have to suffer further.

Owen Moran had not won an elusive world championship. But with

one of his greatest displays, he had written himself into the record books for

all time.

Ad Wolgast at

San Francisco

By Independence Day, 1911, Ad Wolgast was in the ferocious prime

of his fighting life when he defended his lightweight championship against Owen

Moran at San Francisco. Wolgast, the so-called Michigan Wildcat, was surely one

of the most relentless and intimidating men who ever stepped into the ring.

In his savage marathon with Battling Nelson at Point Richmond, Ad

had graphically demonstrated his maniacal and near suicidal desire to win. He

was a furious fighting man, reckless and devil-may-care, no less of a danger to

himself than he was to others. Punching, hustling and charging all the time,

Wolgast would frequently offer his head as bait to his opponent and seemed to

take his pain and punishment with as much relish as he gave it. Before his final

fight in 1920, Ad would already be teetering between reality and fantasy from

the brain damage of his many wars.

It could be said that Independence Day wasn’t the greatest day

for an Englishman to be fighting Ad Wolgast, but the Wildcat never required

special motivation. Like Moran, he just loved to fight.

The two men had engaged three years before in a no-contest in New

York, when Wolgast was still climbing the ladder. By the time of their San

Francisco meeting, Owen was twenty-seven years of age and already grizzled and

jaded from a string of tough battles against talented and hungry men from a

brutal boxing era that we will never truly understand.

Just as the great Nelson had taken his first ten count at the

hands of Moran, so brave Owen would suffer the same fate against Wolgast. Ad set

a breakneck pace and it was quickly evident that Owen would not be able to

contain the Wildcat over the long haul. Much of Moran’s genie-like magic was

still in the bottle, and he was able to comfortably outbox Wolgast from long

range, delighting the crowd with excellent jabbing and footwork and skilful

ducking and slipping. But Owen’s finest work couldn’t prevent Wolgast from

bulling his way inside and wreaking damage with his heavy body blows.

Ad walked through everything Moran had to offer and even took the

play away from the challenger in the clinches. Few men had ever bettered Owen on

the inside, but he simply couldn’t cope with the vicious right uppercuts that Ad

was slamming home. Deceptively clever in his own right, Wolgast was looping many

of these hammer-like blows around Moran’s left arm.

The punishing attack of the champion eventually took its toll,

although Moran’s confidence seemed to lift as the crowd applauded his skill. He

got his second wind in the tenth and eleventh rounds, when he slowed Ad for the

first time with an array of brilliantly timed punches.

Fighting Wolgast, however, must have drained many a man’s morale.

Between rounds, Ad laughed and chatted with friends in the crowd, as if he were

out for a pleasant stroll in the park in his own exceptional world.

No fighter is indestructible, but Wolgast was close to being so

at that stage in his rip-roaring career. Moran was wearing down and even the

feverish attention of his cornermen could inspire him no more. In the thirteenth

round, Owen’s face turned sickly pale as Wolgast drove in a series of terrific

right uppercuts to the stomach. A cut lip had left a smear of blood on Moran’s

face as his tired body spluttered to a halt and began to waver and fall. A final

left hook thudded against Owen’s jaw as he crashed into a sleep that lasted for

some minutes.

As Wolgast’s supporters rushed into the ring to congratulate him,

the champion tugged at the American flag he wore around his waist and exclaimed,

“Some battle for the fourth of July!”

Some battle indeed.

Epilogue

Owen Moran was demonstrating how he knocked out Battling Nelson.

The man gingerly pretending to be Nelson was Owen’s good friend, newspaper

reporter Jimmy Butler. “It was like this,” Moran explained, dropping into a

crouch. He feinted a punch to Butler’s stomach and then cracked him on the chin.

Owen was horrified as Butler staggered across the room, figuring

that Jimmy would have the sense to step out of range. “Gosh, Jimmy, I’m sorry,”

Moran said. “I didn’t mean to hit you.”

How Butler must have loved recounting that story. Owen Moran had

actually apologised for hitting someone on the chin!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|