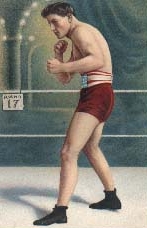

Genius From

The Chicago Stockyards: Packey McFarland

By Mike Casey

He lost just once in well over a hundred professional fights,

that single blot on his magnificent record occurring when he was just a

sixteen-year old novice.

His defence at its best was virtually impregnable, he boxed with

sublime skill and speed and carried a formidable knockout wallop when the

occasion demanded urgency. Quite simply, he was one of the greatest and most

complete boxing masters of all time.

Packey McFarland, the fistic genius from the stockyards of

Chicago, the lightweight who was never truly a lightweight, never won an

official world title. He didn’t have the constant menace and aura of Joe Gans,

nor the obvious majesty and magnetism of Benny Leonard. McFarland didn’t even

have a weight class he could truly call his own. In the stark and tougher days

of eight divisions, he skipped and hovered between the lightweights and

welterweights, compensating for his status of misfit by beating a golden

generation of fighters from both divisions.

Those who saw McFarland in action never forgot him. Huge crowds

marvelled at the hard-hitting, ghost-like maestro who possessed the visual

tricks and elusiveness of a shadow. Boxing journalist tapping out their reports

for the morning editions couldn’t find enough superlatives with which to shower

him.

When McFarland exploded onto the world stage at the Mission

Street Arena in Colma, California, in the spring of 1908, he was hailed as a

boxing wizard without a discernible fault. Former lightweight champion Jimmy

Britt was scientifically bewildered and battered to a sixth round knockout

defeat and everyone was talking excitedly about the new kid on the block.

Ringside reporter Eddie Smith wrote of Packey: “McFarland is

everything, a hitter, a boxer, a good general and wonderfully clever and fast.”

What a pity, then, that Packey constantly had to wage separate

battles to make the old lightweight limit of 133lbs. He was always nearer 135lbs

in his younger days and his title chances were frustrated as a result. Three

times he was meant to challenge Ad Wolgast. Three times the proposed fight fell

through because of McFarland’s weight difficulties.

But how the kid from Chicago made his mark in spite of it all!

His clever and quietly brutal dismantling of the artful Britt was a revelation

to West Coast fans who had read of Packey’s exploits in the Eastern press.

Problems

Britt was apparently wrestling with weight problems of his own at

the Mission Street Arena. Jimmy looked drained and uncharacteristically subdued

when the two fighters came to mid-ring for their instructions. It was normally

Jimmy’s manner to stand tall and stare into the eyes of his opponent, but now

the dapper little San Franciscan was shaking hands with McFarland with a weary

air. When the photographers asked the fighters for another pose, Britt dropped

his hands and shuffled irritably.

Britt’s lethargy shocked reporter Eddie Smith, who noted: “In the

former days, he would have grasped the hand of that opponent and tried to jerk

it out of its socket.”

What followed from McFarland, however, was a master class of

box-fighting in any circumstances. Jimmy Britt fought with terrific courage but

simply couldn’t handle the natural brilliance coming back at him. Jimmy’s

sluggish pre-fight demeanour gave no hint of the fast and enthusiastic start he

made to the contest. He dashed from his corner at the opening gong, slipping

into his familiar crouch and feinting for an opening. He would discover that

openings in Packey McFarland’s defence occurred with depressing rarity. When the

fighters came to close quarters for the first time, McFarland quickly

demonstrated his superior strength and speed of thought with a right hand smash

to the body as they broke from a clinch.

Packey’s clever footwork was quite exemplary as he frequently

made Britt miss by wide margins. Jimmy stumbled to the floor after missing by a

good foot with a left swing. His work was far too urgent and intense, his fiery

aggression denying him the necessary time he needed to assess and measure

McFarland’s capability. Jimmy did have some success with several hard lefts to

the body, but Packey was jabbing and moving around him beautifully.

McFarland was giving the crowd only a foretaste of what was to

come, for it was quite obvious that he was not yet showing his full hand. From

the second round, like a teasing magician, he began to reveal his most

impressive tricks. While Britt was still able to score to the body with his

left, most of his leads and counters were being blocked with great skill by the

young master from Chicago. By the end of the round, Packey was doing all the

leading and out-muscling Jimmy in the clinches.

Britt’s goose was more or less cooked at that early stage. He

simply couldn’t match McFarland for strength or skill. Packey’s seconds told him

to work Jimmy’s body in the third round as the breaking down process gathered

momentum and force. McFarland glided in and out like a man on castors during his

rapid and skilful raids, sometimes making Britt look inept. When Jimmy finally

hit the mark with a right to the head, Packey seemed momentarily disturbed. In

fact he was inspired.

He fired back, taking complete control of the fight and forcing

Britt to employ some clever ducking and blocking to temper the backlash.

Suddenly Jimmy couldn’t keep his assailant out and was punched all around the

ring as McFarland stepped up another gear. Brave Britt managed to summon a brief

rally, but he looked a distinctly dispirited man at the bell.

It was all or nothing for Jimmy from that point on. He knew that

he had encountered a superior talent in all-round skill and that only a knockout

would save the day. He tried gamely to find the big punch, but his greater

daring and its accompanying recklessness only sucked him into further trouble.

Packey smothered Britt’s best efforts and very nearly decked him with a right to

the jaw. Jimmy was being struck repeatedly by his opponent’s hard and accurate

jabs and was being taken apart in the clinches. Then Britt was heard to groan as

he took a hard right hook to the body inside. As he stumbled back uncertainly,

McFarland pursued him and floored him with a right cross to the jaw. Jimmy

looked all through, but the bell saved him and he showed his courage in the

fifth round as he bought himself some extra time with a final attack. But even

as he tried to find the one big shot that would turn his fortunes around, he was

being smothered and shaken by short, jolting blows.

The gutsy little San Franciscan, a plumber by trade, still looked

surprisingly strong as he came up for the sixth round, but no longer was he able

to land a significant blow on his evasive tormentor. Coming out of a clinch,

Britt had the last of his fighting spirit knocked out of him with a big shot to

the jaw. McFarland went for the kill and scuttled Jimmy with a beautifully timed

right cross. There was no hiding place for Britt when he struggled to his feet,

another blow to the jaw sending him to the deck again. When a final right to the

jaw crumpled him for the third time, one special man in the crowd had seen

enough.

Jimmy’s grey-haired father clambered into the ring and pushed

Packey back, signalling that the Britt family was through for the day. McFarland

was overjoyed at his victory, running and jumping around the ring until his

seconds calmed him and took him back to his corner.

The maestro from Chicago would paint many more masterpieces in

the years ahead.

Boxing masters

The lightweight division, historically rich in boxers of great

skill and guile, was a particular hotbed of versatile talent in Packey

McFarland’s era. Packey was a bright jewel in a golden crown, but he one of

several genuine masters who tracked and followed each other’s movements through

the competitive jungle.

When McFarland won a ten-rounds decision over Freddie Welsh, the

artful wizard from Wales, at the Badger Athletic Club in Milwaukee in February

1908, so began a keen rivalry that spanned three fights of immense skill and

clever hitting. Five months later, the shining talents would wage a draw in Los

Angeles, but it was their final meeting in the hushed environs of the National

Sporting Club in London that would prove the most controversial and intriguing.

By that time, Packey had made an adjustment to his technique to

prolong his career and better equip him for the long haul. He was thought to be

boxing with only a half-clenched fist, sacrificing his impressive knockout ratio

in return for less stress and greater stamina. The bad news for his opponents

was there was no discernible difference in McFarland’s exceptional talent for

hitting without getting hit.

It was quiet at the National Sporting Club when Packey stepped

out in his bid to establish beyond dispute his supremacy over Freddie Welsh.

Deathly quiet as it always was. For the hallowed NSC was like no other boxing

venue in the world. One didn’t shout or cheer within its somewhat intimidating

walls. One certainly didn’t yell, “Come on Freddie, my boy” or the like. By

Jove, sir, it just wasn’t the thing to do! The rules of the house stipulated

that the rounds be fought in silence, with only restrained applause in the form

of gentle hand claps during the intervals. A golfer hunched over a two-foot putt

at the Royal & Ancient would have felt no less at home at the NSC.

Imagine the horror of the patrons, therefore, when a cultured

riot – if there can be such a thing – broke out at the conclusion of hostilities

between Mr McFarland and Mr Welsh. Verbal protests pierced the air, fists and

walking canes were waved and nice suits were creased as the members reacted in

disbelief at the draw decision rendered by referee Tom Scott.

McFarland won the fight. There was no doubt about it. Poor

Freddie Welsh, the entirely innocent recipient of a lucky break, knew better

than to give his fellow Brits a cheery wave. Nothing offends them more than the

desecration of fair play.

The sympathy of the throng was entirely with the majestic

McFarland, who, it is probably fair to say, wanted to win that night more than

at any other time in a brilliant career bereft of official gold medals. The

contest was for British recognition as lightweight champion of the world, the

nearest Packey ever got to championship glory.

He was ready for the challenge too, in every way. Even his weight

was right, after much hard work and sweat to get inside the lightweight limit.

James (Jimmy) Butler, one of the greatest and most impartial of

boxing writers, said of the American ace: “Packey, who had sweated in heavy

turtle-neck jerseys throughout his training in order to make certain of his

weight, immediately celebrated by gulping down a quart of egg and sherry mixture

which Jimmy Britt held ready for him.

“Of his fitness, there was no doubt. Nowhere on his slim, wiry

body was there so much as an ounce of superfluous flesh, and if Welsh’s rugged

physique was the more impressive, there was something equally menacing in the

easy grace and speed with which the American moved.”

McFarland was simply wonderful in a captivating, 20-rounds duel

of sublime skill and cunning. He was known now as the prince of stylists and

didn’t disappoint his eager and intrigued audience against the canny and

aggressive Welsh.

The biggest surprise was Packey’s fast and vicious start, which

clearly caught Freddie napping. Lefts and rights from the American, thrown with

marvellous accuracy, penetrated Welsh’s guard and drove him to the ropes. The

contrast in styles was no less fascinating than the contest itself. Where

Packy’s defence was of a pure and classic nature, Welsh’s craftily constructed

bunker was a constantly moving myriad of components. He bobbed, he weaved, he

slipped and feinted. He was an excellent blocker, as were so many of the

thoroughly schooled fighters of the time.

Freddie quickly learned, however, that out-witting McFarland

require the agile and forward thinking mind of a chess master. One of Welsh’s

little mannerisms in his pomp was to wear a quietly withering little smile to

signal his belief that he could not be taken. Not on this occasion. He was far

too busy trying to avoid Packey’s stinging jabs and thumping rights to the ribs.

Always, it seemed, McFarland could find a way through the Welsh Wizard’s

defence.

The pattern continued, resulting in a big shift in the odds.

Freddie had started as the favourite, but Packey was the 2 to 1 choice of the

bookies by the close of the second round.

Welsh clearly needed to be more adventurous and try something

new. But what, if anything, could derail McFarland when he was in such imperious

form? How Freddie must have raged inside when his big gambit in the sixth round

reaped no dividends. He thought he saw the opening he had been searching for so

patiently, putting all his speed and expertise into a mighty right uppercut that

whistled in the direction of Packey’s chin. The blow fell short by a good six

inches. Few in the crowd saw McFarland move, yet he had evaded the punch with

the deftest manoeuvre of his head. Then, almost outrageously, he did it again.

Welsh followed up with a left, only to suffer similar embarrassment. One can

only imagine how humbled Freddie must have felt. It was akin to Jack Nicklaus

scuffing one of his famous drives ten feet through the grass.

What made McFarland such a wonderfully complete fighter was that

he was no backtracking will ‘o’ the wisp. The subtlest of defensive moves always

combined seamlessly with equally intelligent and cultured attacks.

He was all over Welsh one minute and then standing back teasingly

out of range the next. Packey seemed to want the points victory. In his own

mind, that would represent the most forceful confirmation of his superiority.

Through no fault of his own, this would prove to be his only tactical error.

Freddie, to his great credit, never gave up the chase. A Welsh

lad in name and country he might well have been, but his rounded and normally

excellent game had been honed in the furnace of the American school. He finally

came on in the late rounds, enjoying a greater degree of success with some

vicious half-arm hooks to McFarland’s ribs and kidneys. The American ghost

finally seemed to grow flesh and bones as Welsh cut his mouth and left eye with

punches that still packed plenty of steam.

For Freddie, however, the late surge wasn’t nearly enough – or

shouldn’t have been. Referee Scott’s amazing draw verdict was a cruel defacement

of McFarland’s work of art, yet therein lay another sad tale. Within a few short

months, Scott was admitted to a mental institution where he very quickly died.

There was every reason to believe that his mind had been ravaged and unbalanced

for some time.

McFarland never once mentioned the fight when he met up with his

old reporter friend Jimmy Butler some time later. Perhaps that was

understandable bitterness on Packey’s part. Perhaps it was just another touch of

class.

Mike Gibbons

in Brooklyn

Mike Gibbons, the wonderful St Paul Phantom, was something of a

spiritual brother of Packey McFarland. Mike, on his best day, was as hard to hit

as McFarland or any other man in the game. But that wasn’t the only similarity.

Gibbons too, would never win a world championship, nor even challenge for that

greatest honour.

The older brother of light-heavyweight Tommy Gibbons, Mike was a

shining star of the middleweight and welterweight classes, beating the cream of

his era. Among others, he duelled with Jeff Smith, Jimmy Clabby, Eddie McGoorty,

Harry Greb, Ted (Kid) Lewis and Jack Dillon. But all Mike ever got for his

endeavours was a scantly recognised claim to the middleweight title.

When Gibbons clashed with McFarland at the Brighton Beach

Motordome in Brooklyn on September 11, 1915, some 60,000 fans saw a face-off

between the two great untouchables of the game. It was to be Packey’s last fight

and his last great performance.

He was coming out of semi-retirement after nearly two years of

inactivity, and Gibbons was some opponent for a comeback fight. McFarland

however, much like Gene Tunney a little later on, always seemed protected by a

ring of destiny in those great years of his prime. Packey and Gene possessed

precise and lively minds and were among the best ever at formulating and

re-shaping a game plan. Nothing, they believed, was meant to knock them off

their chosen path. When something did, they genuinely couldn’t believe it. It is

said that McFarland, jealously proud of his defensive magic, brooded for days

after getting a black eye from Kid Burns in their New York set-to.

Packey was still lean and strong at 153lbs for his classic

fencing duel with Gibbons, who scaled the same weight. One could understand how

getting down to 133lbs, even as a younger man, had always been such a hugely

taxing experience for McFarland.

The Brighton Beach Motordome was some place to go to watch a

fight. Thirty thousand seats had already been filled by the time of the first

preliminary bout at 8.30pm, the endless throngs of spectators being played into

their seats by a 32-piece band and assisted by 300 smartly attired ushers.

McFarland entered the ring at three minutes paste ten, followed

by Gibbons who paced around testing the boards. Both fighters looked superbly

fit and deadly serious, although Packey did afford himself a little grin when

ring announcer Joe Humphries announced him as, ‘The Fighting Chicago Irishman’.

The frantic clicking of cameras could be heard all around, while movie cameras

and other machines were positioned on a high platform fifteen feet from the

ring.

Nothing could separate the two defensive masters for the first

eight rounds, as they feinted, shifted and bluffed like a couple of wary snakes.

Referee Billy Job was barely noticeable as all eyes were fixed on two of the

great ring scientists and their clever efforts to concoct the winning formula.

Each was occasionally made to look foolish by the other’s brilliance, but it was

McFarland who was the calmer and more measured battler. He would often smile at

friends in the crowd over Mike’s shoulder, conveying the impression of a man

taking a pleasant stroll in the park.

Mike was much more earnest, baring his teeth and often showing

his frustration as he attempted to hit something apart from Packey’s gloves.

Come the ninth round, McFarland commenced his sprint for home. Gibbons enjoyed

an early success as he feinted with the left and then struck Packey with a hard

right to the jaw. But McFarland rallied to get the better of a heated mid-ring

exchange, landing a left-right combination without return. Packey tucked up and

protected himself beautifully as Mike tried to counter.

In the final round, Gibbons had the bearing of a man who knew he

had to force the fight to win it. He tried all he knew to pierce the famous

McFarland defence, but it was the Chicago ghost who was doing the cleaner

scoring. Gibbons took three lefts to the face without return and was also being

punished to the ribs. McFarland was anticipating Mike’s return fire and

staggered the St Paul man with yet another left.

At the final bell, it seemed to many that the mesmerising

McFarland had done enough to secure victory. He certainly had plenty of

supporters. George Holmes of the Oakland Tribune, called the bout for Packey,

describing the Chicago man’s performance as ‘wonderful’. Many others disagreed,

including the Associated Press, which tabbed the fight 7-2-1 for Gibbons. The

New York Times and referee Billy Job called it a draw, which is how the contest

is most often recorded today.

Who really won the fight? Who knows? For this was the indecisive

and muddled era of the no-decision, where the newspapers and anyone else with an

opinion pitched in their two cents worth.

For Packey McFarland and that intelligent and voracious mind that

ticked away inside his head, there were other fields to move on to and conquer.

One somehow knew that Packey would prosper at whatever he chose to do. Settling

in the Chicago town of Joliet in his retirement, he became a very wealthy man in

the contracting and brewing business and served for a time as director of the

Joliet National Bank.

He left a few other special men in his wake. One wonders if a

fighter called Dusty Miller had even an inkling of what he truly achieved way

back in 1904. For it was Miller who knocked out the sixteen-year old McFarland.

Thereafter, the only men to knock Packey off his feet were Ray Bronson in New

Orleans and Cyclone Johnny Thompson in Kansas City.

McFarland at his best probably came as close as any fighter ever

did to making himself invisible. How cruelly ironic that an invisible opponent

finally penetrated his guard and killed him. In September 1936, while serving as

a member of the Illinois State Athletic Commission, forty-eight year old Packey

slipped into a fatal coma from an infection near the heart.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|