Masahiko Harada: Last Hurrah Of

The Little Emperor

By Mike Casey

One of the wonderfully

enduring qualities of boxing is its effortless ability to blast a hole straight

through everything you think you know. You accumulate half a lifetime of ring

knowledge, factor in every conceivable component and then reel back stunned as

all logic and sense flies out of the window.

My father, as worldly a man as

I have ever met, sounded like an innocent who had missed the starting gun when

he told me some years ago of his reaction to Willie Pep's fourth round knockout

defeat to Sandy Saddler. "Nobody knocked out Pep," dad said, still shaking his

head forty years after the event. "It just wasn't done."

Like father, like son. I was

no less shattered when Muhammad Ali humbled George Foreman or when Lloyd

Honeyghan dismantled the imperious and seemingly untouchable Donald Curry. But

my first real jolt came as a ten-year old boy when a Japanese ball of fury named

Masahiko (Fighting) Harada relieved the great Eder Jofre of the bantamweight

championship in Nagoya, Japan. How I idolised Jofre! Nobody had beaten the

Brazilian genius and surely nobody ever would. My childish scenario of the

supreme Eder had him rounding off his professional log at 100-0 before returning

to the temple of the gods from whence he came.

Then I'll be damned if Harada

didn't do it again. He won a thrilling return match in Tokyo to send Jofre

spluttering into the first and only period of uncertainty in his incredible

career. Eder would retire for more than three years before his spectacular rise

from the ashes to claim featherweight honours.

Fighting Harada was far from

being an unknown quantity, yet the shocking vibes of his double whammy over

Jofre were heard around the world. But just how good and permanent was the

little Japanese ace? As a precocious 19-year old, he had won and lost the

flyweight championship in the short space of three months. Would Harada flash

through the bantamweight division in similarly quick time? He would answer that

question emphatically by bossing the 118-pounders for nearly three years. His

eventual dethronement in 1968, at the hands of Australian aborigine, Lionel

Rose, was almost as surprising as the fall of Jofre. The multi-talented Rose, a

natural who never truly fulfilled his wonderful potential, employed some clever

kidology to fool the Harada camp, including passing himself off as a

pipe-smoking man of leisure. Rose outpointed Harada and it seemed that the

Japanese buzzsaw was on he wane as a world class competitor.

Not so! Harada moved up in

weight again and began to attack the featherweights with equal zest and

determination. He outpointed the tough and rugged Dwight Hawkins, knocked out

Nobuo Chiba in seven rounds and posted two other wins against a sole, upset

points loss to the capable Alton Colter. Harada's target was the debonair

Australian world champion, Johnny Famechon, and their first battle would prove

to be one of the most controversial of the decade.

For Harada, a golden legacy

beckoned. He stood on the verge of everlasting glory as he attempted to join Bob

Fitzsimmons, Henry Armstrong, Tony Canzoneri and Barney Ross as one of the

select group of men who had won three undisputed world championships. Even if

Masahiko failed in his quest, his place among history's outstanding world

champions was assured. He had beaten the best men in two divisions, and the

victories over Jofre were the unblemished jewels in Harada's crown.

Jofre, after all, had seemed

to be on a different plane to his peers. He had reigned as champion for five

years and seen off the challenges of Piero Rollo, Ramon Arias, Johnny Caldwell,

Herman Marques, Jose (Joe) Medel, Katsutoshi Aoki, Johnny Jamito and Bernardo

Caraballo. Jofre at least had the consolation of passing his crown to a near

equal. Harada was the epitome of the top class Japanese fighter: intensely

proud, fiercely dedicated, totally committed to his cause. He was never a big

puncher, but rather a pressure fighter who combined aggression with ring

cleverness. His punishing, whirlwind attacks simply wore Jofre out in their

second meeting.

Masahiko had turned

professional in 1960 at the age of sixteen and punched his way to 13 successive

wins before the end of that year, including a six-rounds decision over his

compatriot and future champion, Hiroyuki Ebihara. Harada extended his unbeaten

run to 25 fights before losing a decision to the tough Mexican, Edmundo Esparza,

but the defeat was a mere blip in the youngster's progress. Just four months

later, Harada hit his top form to rip the flyweight championship from the

formidable Pone Kingpetch on an eleventh round knockout in Tokyo. Kingpetch, a

great and determined warrior in his own right who had ended the era of the

fabulous Pascual Perez, quickly regained the crown from Masahiko on a majority

decision in Bangkok. It was a frustrating reverse for the young Japanese tiger,

but his mind was set on frying bigger fish and it was among the bantamweights

that he found his natural home.

Once his feet were under the

table, Harada quickly shut the door in the face of those contenders who might

have believed that Jofre's departure would result in the world championship

being less monopolised. During his tenure as champion of the 118-pounders,

Harada outpointed Liverpool's skillful 'moptop' Alan Rudkin in a superbly

competitive contest and also turned back the challenges of previous conqueror

Joe Medel and Bernardo Caraballo. How one sympathises with Medel and Caraballo,

two class acts in their own right. After being savaged by Jofre, they got Harada

for an encore!

My good pal and fellow writer

and historian, Ted (The Bull) Sares, has always held Harada in very high esteem.

Of the 100 best fighters he has seen down through the years, Ted ranks the

little warrior from Tokyo 34th. Here are The Bull’s thoughts: “Along

with Yoko Gushiken and Jiro Watanabe, Fighting Harada is one of the three

greatest Japanese fighters of all time, but what sets him apart from the others

is that he fought 62 times (55-7), an unusually high number for a retiring

Japanese champion, who generally retire before their 30th fight.

“Like Gushiken, Harada was a

pressure fighter who could alternate between body work and going to the head.

Combined with great stamina, this usually proved effective against his

opponents. Of course, his record could well be 56-6-1 had unqualified Willie Pep

not been appointed the referee and only judge when Harada ‘lost’ to Johnny

Famechon in Australia in 1969.

“I met Harada and his lovely

sister at the Hall of Fame this past June and he is articulate and every bit the

professional, reflecting the high respect with which he is held in Japan.”

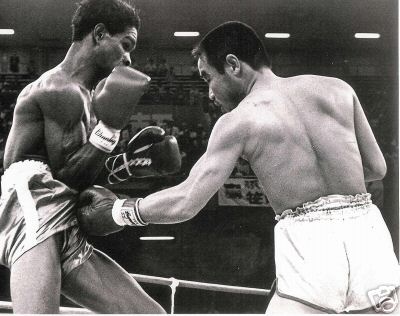

Johnny Famechon

When Harada pitted his fire

and brimstone against the deft skills of Johnny Famechon in Australia on July

28, 1969, boxing fans saw a fight that encompassed all those qualities that make

the Noble Art the ultimate test of a man's mettle. There wasn't just a big

dollop of controversy. There was action, skill, courage and honest endeavour.

It seemed that controversy

followed Johnny Famechon around, most often because his skills were of the

subtlest nature and not always seen or appreciated. There was nothing flashy or

extrovert about Johnny, no gaudy party tricks or exaggerated double takes to

remind the audience of his cleverness. Thankfully (in this writer's opinion at

least), there was less pressure on boxing's true artisans to prove themselves in

the not so distant days of the nineteen sixties. The boxing masters of the game

didn't have to beef up their portfolios with tacky gesturing, meaningless

shuffles or ring apparel that even a Parisien tart wouldn't keep in her

wardrobe.

Famechon had won the world

title on a controversial decision earlier in 1969, when he outpointed the flashy

and skillful Cuban, Jose Legra, in London. I was one of the minority who

believed that decision to be just, having been greatly impressed by the

Australian's clever work. A beautiful boxer, blessed with a superb left jab,

Famechon was a delight to watch, the kind of fistic artist who could make boxing

look as graceful as ballet. I liked the man's style and I liked his attitude.

Like Gene Tunney before him,

Famechon had his life planned out. In 1967, at the age of 22, he was quoted as

saying, "I have given myself until I'm 25. Another three years and I hope

everything I want will be achieved." He didn't mention a world championship, but

one sensed exactly what he meant. How nice it is to have such grand dreams, but

how much nicer to have the talent to be able to fulfill them! Famechon achieved

his goal, but not without years of great dedication and hard work.

Johnny was a professional at

16, having had no amateur experience, but he did have two aces up his sleeve:

classic boxing heritage in the form of his father, Andre, and uncles Ray and

Emile, and a crack trainer-manager in Ambrose Palmer.

As a boy, Johnny Famechon's

interest in the sport blossomed as he watched his father going through his paces

in the gymnasium. At the age of 15, Johnny wandered into Ambrose Palmer's

Melbourne gym, where man and boy struck up the magical relationship that would

help Famechon climb to the pinnacle of his profession. Palmer didn't rush

Johnny. He brought his young charge along slowly and carefully, patiently

correcting his faults and meticulously polishing and refining his style. Johnny

was a raw young boy when he made his professional debut against Sammy Lang in

1961, but was moving up fast by 1964 when he outpointed Les Dunn for the

Victorian featherweight title. Famechon had added maturity to his natural talent

and was improving with every fight.

Four months later, he annexed

his second professional title when he outscored Ollie Taylor for the Australian

championship. Johnny continued to hone his skills with a succession of victories

over international fighters, enabling him to rise steadily up the rankings. When

he stopped Scotland’s John O’Brien for the Empire title in 1967, Famechon could

think realistically of winning the world championship.

Had fate not intervened in the

form of the Spain-based Cuban ace, Jose Legra, Johnny would have almost

certainly challenged Welsh wizard Howard Winstone, who had won the WBC version

of the title by stopping Mitsunori Seki in early 1968. Like so many appealing

matches that never materialised, we can only fantasise about the gorgeous feast

of pure boxing that a Famechon-Winstone encounter would have surely produced.

However, it was Legra who got

the first chance against Howard, and Jose capitalized in grand style by punching

his way to the title in five rounds. Famechon kept busy by stopping Billy

McGrandle in a successful defence of the Empire title, and then came the big

fight against Legra at the Royal Albert Hall in London. A video of that contest

would provide the perfect test for an aspiring boxing judge, for it was a duel

between two men of contrasting skills which revived the age-old question of how

a fight should be scored. Legra was unquestionably a highly competent ring

mechanic, as his lengthy and impressive record proved, but too often his

colourful, showboating style made him flatter to deceive.

Famechon was a plainer and

purer artist, whose style was uncomplicated and devoid of unorthodox moves.

Against Legra, Johnny’s work was frequently made to look unattractive, but he

doggedly stuck to the prime task of scoring points and referee George Smith was

astute enough to see the wood for the trees.

However, Famechon was soon to

prove that he possessed the heart and grit to go with his subtle finesse, as

well as the capacity to thrill the crowd. It took the ferocious Harada to unlock

those harder qualities in the young Australian. When the two men locked horns on

Johnny’s turf at the Sydney Stadium, Harada was eager to silence the partisan

crowd by showing that there was still fire in his soul and power in his punches.

He would come agonizingly close to victory and be denied only by a bizarre set

of circumstances The heavier man by one and a quarter pounds at 125 3/4lbs,

Masahiko took the fight to Johnny in characteristically aggressive style, and

referee Willie Pep, the legendary featherweight boxing master, simply let the

fighters fight. In fact Willie was later criticised for being too relaxed in his

approach to the roughhouse fighting that was to develop. Pep’s leniency would

prove to be the least of his indiscretions. Let us say, for diplomacy’s sake,

that as a referee Willie Pep was one heck of a fighter.

Famechon, boxing smartly

behind his left jab, narrowly won the first round, but in the second his grip on

the title slipped alarmingly as Harada sprung the first sensation. Johnny was

faring well when the fiery challenger suddenly found the range with a heavy

right to the jaw. The blow shook Famechon and for a split second he seemed to

freeze like a mime artist. Harada saw his chance and winged in two more rights

to the head to send Johnny to the canvas.

The champion was clearly

dazed, and after taking the mandatory eight count he attempted to clear his head

as he held on to Harada. Famechon fought back towards the end of the round, but

the knockdown had fuelled Harada’s confidence. The veteran campaigner maintained

his advantage in the following rounds as he continued to pressure Johnny. The

champion kept pumping out his jab as if the punch were a remote machine strapped

to his shoulder, but it seemed his natural skill wasn’t enough to contain the

fiery man from the Orient.

Then a shaft of light suddenly

appeared for Johnny in the fifth round when he uncorked a long left hook that

caught Masahiko as he was moving away. The challenger went down and it appeared

that the pattern of the fight might be changing. But two-time world champions

are fashioned from special material and Harada stubbornly refused to surrender

the initiative. Famechon tried hard to capitalize on his great chance, but

Masahiko scored with a hard right to the head and it was apparent that he was

still highly alert and dangerous.

As the fight swung into the

middle rounds, the advantage shifted subtly from one man to the other, as

Famechon jabbed and counter punched impressively and Harada attacked with all

his old beef and zest. Johnny proved his mettle as he repeatedly took hard

punches and replied with some graceful and classy boxing, but as the battle

reached its later stages, so it was clear that he was being overtaken by his

determined challenger. Harada was an absolute dynamo when he got up a head of

steam. Much like Henry Armstrong, Harry Greb and the young and lithe Roberto

Duran, the Japanese terror kept hunting and hustling and throwing. Someone once

said of Duran that he seemed to be trying to punch his way right through Jose (Pipino)

Cuevas. Natural born warriors always give such an impression. The sophisticated

world shrinks right down into their one square little acre where the only

important consideration is the winner of the oldest test of supremacy there is.

Now Famechon knew what it like

to share an oven with a man of such intensity. In the eleventh round, Johnny was

forced to employ all his evasive skills as Harada swarmed forward with great

purpose. The fighting was rough and tough, and while the battle couldn’t be

termed a thrilling affair, it was certainly an engrossing struggle that fizzed

with incident and suspense. As hard as he tried, Johnny couldn’t solve the

problem of Harada’s fast right hand, which whipped across with force to spill

the champion for the second time in the fight. It was here that Famechon got his

first big break. Referee Pep ruled the knockdown a slip, yet curiously sent

Harada to a neutral corner to cause an unnecessary delay in the action. Why, oh

why, had the great Willie been given the job? Nothing infuriates a fighter more

than an unjust pause in the action when he is in full flow.

Famechon held on desperately

as the two fighters grappled on the ropes. The champion now looked in imminent

danger of being overwhelmed. Again he clawed his way out of trouble, but his

instinct and his guile were no match for Harada’s burning desire to win.

Masahiko had his third championship firmly in his sights and was fighting with

that magical drive of a man who knows he can’t be beaten.

In the thirteenth round,

Johnny tried manfully to turn the tide, but enjoyed only a few successful

moments and was grateful to clinch whenever he could. Even his most ardent

supporters must have feared that the crown was slipping from his head, yet the

game champion kept throwing punches even though his blows now lacked authority.

The last two rounds of the

fight must have seemed like an interminable nightmare for Famechon, as Harada

laid all his cards on the table and steamed forward with the intensity of a man

possessed. Johnny’s resistance was draining rapidly, and in the fourteenth round

his senses were scattered again as Harada cut him down with a ferocious right

cross. But the gods were most certainly with Famechon on this crazy and frenetic

night, for he arose just before the welcome sound of the bell and was able to

plod back to the sanctuary of his corner. Had Masahiko timed his onslaught with

greater precision, he would have surely won the championship in that round.

Sensing his chance of a

stunning victory, Harada mounted another furious attack that had Famechon in

complete disarray in a wildly exciting fifteenth and final round. Johnny sought

shelter from the storm, but could find no place to hide as the punches rained

in. He was driven around the ring to cries of “Stop it!” from the crowd of ten

thousand. Instinct made him clutch at Harada whenever possible, but it looked

for all the world as though the brave champion was on his way out. However,

referee Pep allowed the action to continue to the final bell and then came the

controversy.

Prising the fighters out of a

clinch, Willie signalled a draw by raising both their arms amidst a storm of

booing. Famechon’s face broke into a huge smile of relief, while Harada bore the

astonished look of a man who had just cracked a safe after much ado and been met

with a greeting card that read, ‘Ever been had?’

The booing and jeering

increased when Pep re-checked his card and discovered that Johnny had won the

fight by a point. It was a confusing and unfortunate ending to a splendid

battle, leaving Famechon as a tainted champion and Harada an unlucky victim of

cruel fate. There was a touch of irony to Johnny’s success, for in 1950 his

uncle Ray had failed to win the same title when challenging, of all people,

Willie Pep!

A return fight between

Famechon and Harada was in order to settle the question of supremacy and in

January, 1970, the two fighters came together again on Harada’s home turf in

Tokyo. For Masahiko, however, it was too late. In an incredible battle that

surpassed their first meeting for excitement, Famechon proved himself a

thoroughbred champion by surviving a knockdown to knock out Harada in the

fourteenth round.

It was the end of the road for

the grand little emperor from the Land of the Rising Sun, and he was sensible

enough not to try his luck again. After all, when you’ve beaten Eder Jofre

twice, you have no need to worry about your place in the history books.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|