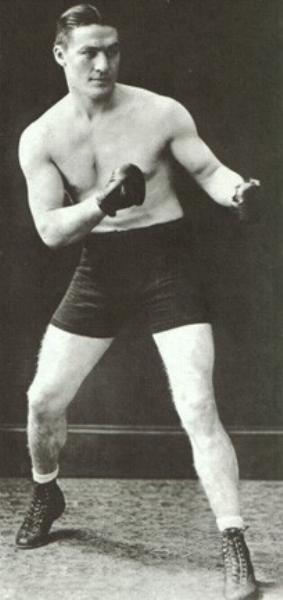

Tommy Loughran: Poetry in Motion

By Mike Casey

Some fighters,

the truly great fighters, transcend the boundaries of time and technique. They

render academic the arguments of those who would tell us that you can draw a

definitive timeline between the great and the not-so-great fighters in boxing

history. The special few slice through all the doubts and debate because we

instinctively know that they would have stood up and flourished on any stage in

any pocket of time.

Watch Tommy

Loughran on film and you will see a timeless boxer of sublime skill and elegance

who could fit snugly into any era and still be the master and commander of deft

skill and graceful movement among the 175-pounders. Watch him ghosting around

Jim Braddock, who, we tend to forget, was being described as a sensational young

contender and a terrific hitter in 1929 before being shunted into the sidings

and re-emerging as the Cinderella Man.

Loughran, the

maestro from Philadelphia, The Phantom as many called him, was a natural who

made lesser man square up to their mirrors and wonder why they couldn’t

duplicate moves that seemed so ridiculously easy. Lean and athletic, fast and

fluid, there was nevertheless an almost slow and casual air about the way in

which Tommy jinked and danced and slotted perfect punches through the tightest

of guards. He was so often referred to as a dancing master, yet he didn’t have

to dance that much in order to avoid incoming blows. That handsome head would

shift this way or that and the blow would meander off into no man’s land like an

errant torpedo.

Unlike many of

today’s pretenders, who only seem to read half the instruction book before

dangling their arms by their waists and getting smashed on the chin, Loughran

held his hands low because he first learned how to avoid being hit. He drilled

himself tirelessly in his quest to become as perfect a boxer as he could ever

be. He berated himself for his mistakes and practised even harder. You can see

it in his great balance and skilful movement and the way in which he could move

forwards, backwards, sideways or suddenly go on the offensive with equal ease

and grace.

How Jim Braddock

tried to nail Tommy down in their Yankee Stadium battle for Loughran’s world

light heavyweight championship. But Jim couldn’t fathom Tommy from a distance

and found himself tied in knots when he tried to take the fight inside. What’s

he going to do next? That’s what Braddock seemed to be asking himself. Loughran

was equally adept at throwing shadows as he was at throwing punches. When he

seemed set to fire the jab, he would lead with a fast left hook. His left-right

combinations were thrown with that deceptive, lightning speed that appears

almost slow and lazy to the naked eye.

Braddock, with

typical honesty, would later say, “I figured I had to try to fight Tommy, not

box him, because, as far as boxing goes, I would have been outclassed, and he

beat me in 15 rounds easy with his boxing ability. He was a guy you could never

hit with a good solid punch.”

Did Tommy

Loughran have a significant weakness in his boxing make-up? Well, if we are

nit-picking, Tommy was no big hitter. He couldn’t sock like Archie Moore, Bob

Foster or the oft-forgotten Astoria Assassin, Paul Berlenbach. But such were

Loughran’s exceptional boxing skills, it would be somewhat trite to play up his

lack of a killer punch, since he so rarely required knockout power in his prime

years as a 175-pounder. Nicolino Locche and Maxie Rosenbloom were no less adept

at prospering without the big wallop. Look at their sprawling records and try to

spot the KO wins without a magnifying glass.

My good friend

and fellow historian, Mike Hunnicut, was all too eager to talk about Tommy

Loughran. Mike owns an extensive film collection of the great fighters and has

studied Tommy many times. Here’s what the good Mr H says: “Loughran was just a

boxing master, able to figure out and do different things all the time. He was

able to consistently creep up on his opponents without them or their trainers –

all of whom knew what he was doing – able to stop him doing it! He had tireless

legs. If, as he was coming in, his opponent tried a barrage, Loughran was off to

the sides or off to the races. He could do that for 15 rounds without too much

difficulty. He was also a master at slipping, feinting and tying up opponents.

This takes a lot of experience, practice and conditioning, which Loughran

obviously had.

“Any light

heavyweight who can post wins over Harry Greb, Max Baer, Mickey Walker and Jack

Sharkey has to be something very special, which Loughran was. He fought and

found ways to beat so many top class fighters of all styles, from tough sluggers

and one-man riot squads to the slickest of boxers like himself. His footwork was

such that at times he seemed to be skating in the ring, whilst simultaneously

picking out punches in mid-air.

“Tommy was a

phenomenon, who remained so due to his utter obsession to his craft. He truly

did train as much as any fighter in history, with wall-to-wall mirrors to study

himself, various diagrams for footwork, and analysing every single move and

punch in constant preparation for his opponents and their styles, strengths and

weaknesses. His trainer Joe Smith would throw fast punches at Tommy’s face,

while Loughran stood near a wall, to master slipping and rolling.

“Tommy Loughran

was one of a kind, like Willie Pep and a few select others. Tommy is synonymous

with the word ‘boxing’”

Meticulous

In the early

1970s, Loughran described his painstaking pursuit of perfection to author Peter

Heller. While Tommy was never one to be hindered by modesty, there is great

truth in what he said: “I think that nobody has ever put in the time and effort

and practising and studying boxing, doing different things, like I did. I was so

meticulous about everything I did insofar as my training was concerned, my

movements, my balance, my sense of co-ordination and my footwork was tied in

with all the movements. Of course, I was fortunate too in having a manager who

had been a fighter himself. Joe Smith had had 300 fights and he didn’t have a

mark on him. Very good looking.

“I worked in the

basement of my home. I had a little gym fixed up there and I had mirrors and I

studied myself in the mirrors, punch the bag, skip rope, shadow box, and I

studied my movements in these mirrors in such a way hat I knew exactly how I

appeared to every fellow that I was boxing.”

Loughran was born

in Philadelphia in 1902 and had his first professional fight as a 17-year old in

1919. Like most fighters of his tough and competitive era, there is really no

telling how many fights he had before wrapping up his career in 1937. The BoxRec

database has his total standing at 174. Loughran himself claimed to have had 227

bouts, which is entirely possible. Whatever the official figure, and we might

never know, it is the quality of his opposition that jump off the page and

stagger the eye, most of whom Loughran vanquished or held even in the old days

of newspaper decisions.

If ever a man

could drop names to impress, it was Loughran. He fought Jimmy Darcy, Bryan

Downey and Mike McTigue. Tommy locked horns with Harry Greb six times and gave

Gene Tunney such a battle of wits and skill in their 1922 clash that Gene would

never entertain the clever Philadelphian again. Loughran took on Johnny Wilson,

Jack Delaney, Young Stribling, Georges Carpentier, Jimmy Slattery, Leo Lomski,

Pete Latzo, Mickey Walker, Ernie Schaaf, Jim Braddock, Max Baer, Johnny Risko,

Paolino Uzcudun, Jack Sharkey and Arturo Godoy.

Boxing historian

Tracy Callis says of Loughran, “Tommy was a beautiful boxer to watch in the

ring, a man with picture perfect form. He moved well – fast on his feet, smooth,

quick, elusive – displaying the ultimate in boxing savvy. He was not a

paralysing puncher, but he did everything else well. A boxer supreme, clever

Tommy could handle large men or small men with ease.

“His talent at

movement and boxing tactics was admired greatly by Jim Corbett, the famous and

innovative heavyweight champion, who attended many of Tommy’s bouts. Many boxing

people and historians assert that Loughran perfected moves that Corbett had not

yet worked on.”

Loughran

performed more than honourably when he graduated to the heavyweight division in

an era when holding the 175lb crown was never going to make a boxer rich. That

harsh fact was a great pity to some of the great men who reigned at that weight,

notably Loughran, who was never better than when he was bossing his natural

domain. This, then, is primarily an appraisal of Loughran the light heavyweight

at his classic best.

Was Tommy a Fancy

Dan? Stylistically, yes. But here was a pugnacious man of grit and huge

self-belief who would fight all-comers and actually relished the chance of

sparring with Jack Dempsey. Loughran wouldn’t suffer the put-down from anyone,

in or out of the ring. Not surprisingly, perhaps, it was Tunney who made Tommy

bristle the most.

Gene’s

unfortunate habit of making a compliment sound like a thinly veiled insult never

ceased to grate with Loughran. In 1928, former welterweight legend Jack Britton,

considered to be an excellent judge of fighters, offered his opinion on Loughran.

Said Jack, “There’s only one fighter in the game I wouldn’t bet against in a

fight with Tunney. And you’ll probably laugh when I mention his name. Tommy

Loughran. You know, you can’t knock out a fellow or beat him if you can’t hit

him.”

To this, Tunney

allegedly replied, “I understand that Tommy is a very nice fellow and a

gentleman. But as to fighting – ah! That’s different!”

Loughran quietly

seethed over the fact that Tunney had got to the fading and distracted Jack

Dempsey first in 1926. Never shy in promoting his own credentials, Tommy said,

“I licked Dempsey in his training camp and I know I could have knocked him out

in a real fight, but Tunney had the jump and got the chance. I came near beating

Tunney when I was just a novice and I know I can take him now because all he can

do is back away and counter.”

As a person,

Tunney impressed Loughran even less. “Who does he think he is?” Tommy barked.

“He wasn’t born any better than I was. He never could fight and I can. He didn’t

win the war and neither did I.”

It seems that

Loughran’s nose was put out of joint when he clashed with Tunney at a classy

hotel in Newark, where Gene believed he was the exclusive guest of honour.

Tunney was shocked to see Loughran and a few other fighters in the lobby. The

story goes that Gene approached Tommy and gave him a somewhat frosty handshake.

The ensuing conversation reportedly went as follows:-

“What are you

doing here, Tommy?”

“Just waiting

around.”

“I’m awfully glad

to see you in a place like this.”

“What are you

talking about?”

“Why, I mean that

it is good to see some of the boxers in respe4ctable places. It will help the

public get a different opinion of the business if they see boxers in places like

this.”

Loughran was

apparently boiling by this point and replied, “You don’t know how to act in a

respectable place and I do. If I didn’t, I’d let you have one.”

Well, folks, we

take this story as we will. For while Tunney’ aloofness made many people quietly

fume, so Loughran was just as full of himself in his own earthier way. Both men

might have been more greatly admired if they had tempered their confidence with

a dash of humility. Loughran told the tale of Jim Corbett marvelling at Tommy’s

skill and telling him he did things in the ring that Jim could only dream of

doing himself. Georges Carpentier was another who apparently confided to

Loughran that Tommy was the greatest thing since sliced bread. These stories

might well be true, but should the recipient of such praise really shout it from

the rooftops?

Some years ago,

golfer Greg Norman walked into the press room after shooting a particularly

outstanding round and declared, “I was in awe of myself out there.” Now, one

surely shouldn’t express such thoughts out loud. Your writer immediately wanted

to reach for the sick bag. Greg, the so-called Great White Shark, was promptly

lambasted for this faux-pas by a famous rugby player who had jumped through far

tougher hoops. One began to understand why Norman’s fellow Aussie, Jack Newton,

cut from tougher cloth, had re-christened Greg the Great White Fish Finger.

Loughran,

likewise, could never sufficiently emphasise how he had given Jack Dempsey fits

in their sparring session of 1926, as Manassa Jack prepared for his first battle

with Gene Tunney. Well, I can entirely believe that the lithe and young Loughran

gave the rusty Dempsey the run-around. But to hear Tommy tell it, the ring was

awash with Jack’s blood and broken bones: “Geez, boy, what I didn’t do to him.

The year before, he had had a nasal job, his nose was all shortened, and they

didn’t know whether it would stand up under punishment. I let him have it on the

nose. Blood squirted in all directions. He stepped back and cussed me out loud

and when he did, I grabbed him and turned him around and put him up against the

ropes.. Geez, I poured it on him. I gave him such a beating. I hit him in the

belly, hit him with uppercuts, hit him with a hook, caught him with another. I

had his eyes puffy, his nose was bleeding, he was spitting out blood. I had him

cut under the chin and I think his ear was bleeding. I don’t know whatever held

him up. He always came tearing back in, no matter how hard I hit him.”

The impression is

gained from this is that Dempsey was lucky to make it to the Tunney fight

without the aid of a body cast. Yet within this windy tale of Tommy’s is a great

pearl of wisdom and truth which stood him in good stead and made him a

wonderfully spirited fighter as well as a wonderful boxer. “Confidence is what

it takes,” he said. “Those two rounds with Dempsey gave me confidence in myself.

I learned an important lesson that day: never to be defeated by fear. There are

so many people that are, you know.”

A Slashing

15-Rounder!

Fear and near

defeat came knocking at Loughran’s door in his astonishing and thrilling fight

with the big-punching Leo Lomski at Madison Square Garden on January 16, 1928.

Tommy was defending his light heavyweight championship for the second time,

having relieved Mike McTigue of the title and seen off the challenge of the

brilliantly clever but wasteful Jimmy Slattery. Lomski was a true assassin of

the ring, a gifted hitter from Aberdeen, Wisconsin, who willingly engaged

Loughran in what one reporter aptly described as ‘a slashing 15-rounder’.

It was a torrid

test of endurance that proved to be one of Loughran’s finest hours. Like that

other great boxing master, Benny Leonard, Tommy demonstrated that he was also a

tough and pugnacious competitor who could rough it in times of crisis and battle

his way back from the brink of defeat. The 15,000 people who saw the see-saw

battle in the Garden shouted themselves hoarse as Lomski came out like a train

in the first round and decked Loughran twice. Tommy showed outstanding powers of

recuperation and fighting heart in surviving the crisis. When the fog cleared

from his brain, his agile mind worked out the answer. He realised that fancy

boxing alone would not douse the fire of the rampant Lomski. Moving carefully

and punching accurately, Tommy set about slowing Leo down with a tattoo of hard

jabs and stinging right crosses.

It was a hugely

admirable comeback, for Loughran really was clattered in that epic first round.

Lomski’s first knockdown punch, a crunching right to the jaw, sent Tommy

crashing down by the ropes and very nearly forced him head over heels. Lomski

could hit like a kicking mule – look at the man’s record. He would surely run

riot in today’s 175lb division. Badly shaken, Loughran was up on his feet at

‘six’, but couldn’t extract himself from the eye of the storm. Another big right

to the jaw dumped him again later in the round, and it seemed that the

untouchable phantom had finally solidified and become a vulnerable target.

Loughran’s mind

was all over the place when he got back to his corner. “What round did I knock

him down in?” he asked his seconds. Yet, like all fighters touched with

greatness, he found a way to re-connect his brain to his body. He held his own

in the second round, lost the third, but then steadied himself up and began to

show his mettle in full. Lomski, for all his formidable power, wasn’t nearly

Tommy’s equal in either skill or versatility. Yet Tommy didn’t just outwit Leo

for the rest of the way. Loughran brought the Garden crowd to fever pitch by

outpunching Lomski in a series of ferocious exchanges. Left hooks and right

crosses sent the blood flowing from Lomski’s left eye, but Leo never stopped

trying and hammered back to have Loughran in fresh trouble in a thrilling sixth

round.

Once again, Tommy

shook the cobwebs from his head and finally assumed control of the fight. Stiff

jabs and right crosses repeatedly jerked back Lomski’s head as Loughran began to

pull clear. Lomski, however, proved Tommy’s equal in courage and persistence.

Leo kept punching away, hurting Loughran with some powerful rights to the heart

in the tenth round. But the steam was going out of Lomski’s punches, even though

he was obviously loving every minute of the violent scrap. A smile of pleasure

would often crease his face as he piled in and tried to smash down the boxing

master. Despite going down to a brave points defeat, Leo had become the first

man since Tunney to put Loughran on the floor.

Elite

Boxing historian

and writer Mike Silver is among those who rates Loughran among the elite of

master boxers. Says Mike, “Tommy was without question one of the greatest pure

boxers of all time. He was a classic, stand-up defensive stylist in the mould of

Jim Corbett, Mike Gibbons, Gene Tunney and Jack Delaney.

“In his prime as

a light heavyweight, Loughran combined accurate left jabs with superb footwork,

timing and balance, in addition to a ton of experience. He was adept at

slipping, riding or blocking counter punches and tying up an opponent when

necessary. Loughran never plodded or shuffled. He bounced. His rhythmic

footwork, along with that ubiquitous jab, was the key to his success. It was

like watching a ballroom dancer who, through endless hours of practice, has

perfected every little nuance of his art. And let’s not forget that Tommy had to

overcome certain limitations, specifically his oft-broken right hand, which he

rarely threw. Imagine if the man could punch!

“Loughran

effortlessly moved in or out and from side to side, often just a few inches out

of range of his opponent’s punches, but always in position to jab or counter

with the occasional hook, uppercut or cross. And he did all this as a

practically one-armed fighter! Loughran often seemed to become more effective in

the later rounds of a fight, due mostly to his opponents becoming ever more

frustrated and rankled as they failed to hit him with a solid punch. Tommy knew

his profession inside out and it showed. If you want to become a fighter and

improve your chances of walking away from this sport with your mind intact, copy

Tommy Loughran’s style.”

Mike Silver

believes that Loughran’s great vision and foresight in the ring were among his

greatest gifts. “He had great boxing ‘eyes’ in the sense of his awareness and

perception of what was going on in the ring and what he had to do to win.

Loughran knew where the next punch was coming from and he knew exactly where his

own punches were going. It was as if he had some kind of boxing radar. His

co-ordination of hands and feet was superb. He was a constantly moving target

and was very cool under pressure or when tagged, and rarely hit with the same

punch twice. Significantly, in every film available, he is never ever trapped in

a corner or on the ropes. He did not have that extra dimension of being a hard

puncher, which makes his consistent performances against so many quality

opponents for so long all the more remarkable.”

Punchers

While Loughran

couldn’t punch that hard, he could handle the punchers just fine. Against Mickey

Walker and the young Max Baer, Loughran was the consummate matador,

wrong-footing the bulls with constant movement and dazzling artistry. Walker

gave it all he had in trying to take Tommy’s light heavyweight crown at the

Chicago Stadium on March 28, 1929. But Mick didn’t have enough to beat Loughran.

Referee Dave Miller somehow had Mickey winning the ten rounds battle, but the

judges and neutral observers saw Loughran winning handily. Tommy’s trusty jab,

almost metronome-like in its reliability, kept the frustrated Walker at bay for

most of the contest. Zipping right crosses also checked Mick’s advances.

As the fight

neared its end in the tenth round, Tommy went through the gears with that

certain assuredness and smoothness that only the true naturals possess. His

slipping and ducking was exemplary. Scoring with three straight lefts, he ducked

a left and right to the head, stepped inside of a right and made Walker miss

with a long left. Mickey was then struck by two more lefts and two more rights

to the head before finally finding Loughran with a wild shot to the jaw.

Mickey put in his

usual sterling effort, but, like so many others, he found that hitting Loughran

cleanly was akin to trying to pick a fly out of the air.

The still

maturing Max Baer was given a rare boxing lesson by Loughran in their

heavyweight ten-rounder at Madison Square Garden on February 6, 1931. Tommy’s

master class was watched by a fascinated audience of 12,000, the biggest of the

indoor boxing season up to that point. Loughran was way ahead of the powerful

and willing young Baer, stepping elegantly around the heavier man and rapping

him constantly with accurate jabs. Many reporters were reminded of Tommy’s

classic boxing performance in retaining his light heavyweight championship 18

months before against Jim Braddock. Loughran’s victory over Baer was unanimous

from referee Jack Dempsey and the two judges. The Associated Press gave Tommy

all ten rounds.

Loughran’s speed

of hand and foot against Baer was a reminder of how Tommy had ruled the 175lb

division with such class and dominance. He kept Max off balance all night long

with stinging jabs and whipping right uppercuts. Baer rushed and swung in an

earnest effort to sweep away his smaller tormentor, but Loughran simply wouldn’t

be caught. Baer himself couldn’t hide his admiration of Loughran’s handiwork.

Max often emitted a wry smile as he repeatedly winged his famous right hand wide

of the target.

Only in the third

and ninth rounds did Loughran get a little too full of himself. On both

occasions he attempted to slug with Baer, but Tommy quickly returned to his

traditional boxing after getting banged with a few lusty clouts.

Max, at just over

200 pounds, outweighed Loughran by more than seventeen-and-a-half pounds that

night.

How Great?

In this writer’s

opinion, Tommy Loughran’s place in the pantheon of the truly great light

heavyweights is beyond question. On his very best night, he might just have

taken all of the elite names, such as Tunney, Langford, Ezzard Charles and

Archie Moore. Let us remind ourselves that Tommy was still maturing when Tunney

only edged him.

I was interested

to get the thoughts of the aforementioned Mike Silver on Tommy’s all-time

standing, and here are Mike’s views: “I think he definitely ranks among the

golden dozen light heavyweights of all time. Is he beating a prime Ezzard

Charles or Billy Conn? I honestly can’t say for sure. Tough call with John Henry

Lewis too. A great boxer with a good jab and speed would have the best chance

against Loughran. Tunney shaded him. But I would never count Loughran out

against any other great. Archie Moore would be too slow, I think, but always

dangerous with his punching power.

“But in almost

200 fights, Loughran was stopped only three times and never as a light

heavyweight. I don’t see Bob Foster knocking him out. Loughran is avoiding

Foster’s hook and outpointing him. And don’t forget Loughran did much better as

a heavyweight than Foster. This wasn’t because Tommy had a better chin – you

just couldn’t nail him.

“I would love to

have seen Loughran against Harold Johnson – a purist’s delight. Let’s face it,

today Loughran would be heavyweight champion.”

Now there’s a

debatable point to end on!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|