Climate of

Hunter: Danny Lopez in Africa

By Mike Casey

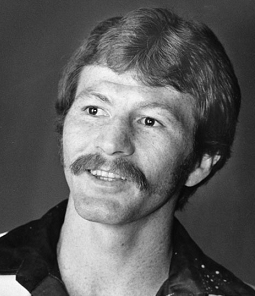

Growing up, I loved Danny ‘Little Red’ Lopez. I loved the way he

fought and I loved the way he looked with that tall and rangy frame and that

eternal glint in his eye of the natural born hunter. The moustache that later

accompanied the famous shock of bushy red hair would perfectly complement the

appearance of an old-style gunfighter out of time, blazing a trail with flesh

and bone instead of pig iron.

Danny Lopez shot down plenty of guys in the ring, from fellow

prospects in the early days to bullish and fearless young challengers who came

to dethrone the tall and laconic world champion that Lopez became in his wildly

exciting prime. What made those showdowns so thrilling was that Danny was in no

way the untouchable Western hero of movie folklore. He was a carefree Doc

Holliday who would take a bullet or two himself and sometimes hit the barn door

before the man.

Back in 1974, I recall the agonising wait here in England for the

result of the dream match at the LA Sports Arena between Danny and the brilliant

young Bobby Chacon. It was a hugely anticipated shootout between the

featherweight young guns of the West Coast. While Lopez had been born at Fort

Duchesne in Utah, he had based himself in the Los Angeles suburb of Alhambra.

Chacon hailed from Pacoima in the San Fernando Valley. I was a fan of both

fighters, but Danny was my favourite.

In the comparatively dark and information-starved age of the

seventies, boxing results could take longer to cross the ocean than migrating

birds. Then I saw it in the paper. Chacon had stopped Lopez in the ninth round.

Boxing was already taking a back seat to other sports and that was all the

detail I got. No report, no explanation. It was tough going back in those

pre-Internet days. I am reminded of the old anachronistic joke where two

prehistoric cavemen trudge for days in search of food. One turns to the other

and says, “I wish some clever bastard would hurry up and invent the wheel.”

How I wished I had been among the throng of 16,027 that sat

enthralled at the Sports Arena. Lopez and Chacon were little men but mighty big

ticket sellers. A further 2,671 closed circuit TV fans were in attendance at the

Olympic Auditorium just a few blocks away.

The reports in the trade magazines didn’t make pleasant reading

for a Lopez rooter. Danny was already a wonderful battler at that stage in his

development, but the fast and dangerous Chacon was better. The best punches that

Lopez could offer failed to deter Bobby or check his impressive advance. Danny

kept pressing but kept eating Bobby’s stiff jabs and right crosses at the same

time. The crisp and sharp blows opened a slit over Lopez’s right eye in the

second round, which required the constant attention of his handlers thereafter.

Chacon really was a very special talent at that age, and I have always wondered

how much greater he could have been if his stop-start career had not been

plagued and pulled apart by his inner demons.

Bobby controlled the fight all the way and had the look of a very

confident fighter as he bounded from his corner at the start of the ninth round.

He met Danny in the centre of the ring and sent him to the ropes with a heavy

right. Lopez was clearly in trouble and Chacon was on him in a flash, driving in

two more rights and a left that sent Danny tumbling onto the bottom strand of

the ropes. Another series of punches sprung the Alhambra youngster from his

temporary trap and deposited him on the canvas.

The one lesson Danny Lopez taught us in this fight was that he

was never dead in his own mind. Always he got up. Always he fought back. He rose

to fight back against Chacon, but a fusillade of blows sent Danny reeling and

propelled him into the ropes on the opposite side of the ring. Referee John

Thomas had seen enough and halted the contest.

Lopez had lost for the first time in 24 fights and was typically

forthright in defeat. “He was tough inside,” he said of Chacon, “a lot better

than I thought he was. He didn’t hurt me until he dropped me. Then he hurt me

pretty good.”

Danny was just twenty-one and had yet to reach maturity. He was

under the featherweight limit at 123 1/2lbs and knew the problem. “I didn’t come

in heavy enough. He was just a little bit too strong.”

Honest words from the man who would be king just two years later.

Midnight

It was past midnight at the Accra Sports Stadium in Ghana, yet

the temperature was still well into the eighties. A pulsating record crowd of

more than 100,000 people only served to stoke the shimmering furnace. Tribal

drums boomed and the people cheered as they awaited the arrival of their hero,

WBC featherweight champion David ‘Poison’ Kotei.

To step into that kind of cauldron and challenge such an

immensely popular champion must send a shiver down the spine of the bravest man,

even though most boxers feel obliged to deny any feelings of fear and

intimidation.

Yet if there was fear in the heart of Danny Lopez in that heady

atmosphere, then it did not reflect in his performance. The twenty-four year old

challenger had waged most of his battles in his hometown of Los Angeles, and it

was a long flight and something like eight inoculations from Los Angeles to

Ghana.

But Lopez was one of those exceptional men who could win wherever

the plane set him down. He possessed that special brand of fighting spirit that

sometimes drives a man beyond the boundaries of common sense and safety. You

could cut Danny, you could outbox and maybe even outpunch him, but you couldn’t

destroy his will to win.

Against Kotei, Lopez was a revelation, a tireless puncher who

shut his ears to the partisan crowd and pounded his way to the greatest victory

of his career. It was hard to believe he was a man in a foreign land, a man

deprived of the invaluable presence of his trainer, mentor and friend, the

72-year old fox Howie Steindler.

Howie’s age and health prevented him from making the trip, and

the absence of such a wise old general might have had a telling effect on any

other young fighter. Not Lopez.

I was approaching manhood when Danny was carving a big name for

himself on the West Coast of America. For many years, there was a section in The

Ring magazine titled, ‘In Sunny California’, which I would scan religiously in

the early seventies for reports on Danny’s fights.

A big puncher, Lopez was also easy to hit, and so many of his

fights seemed to be the see-saw, drama-laden slugfests that appeal to a thrill-

seeking youngster. His background was no less colourful. For the first eight

years of his life, Danny was raised on an Indian reservation in the

north-eastern region of Utah. Then his parents broke up and he and his elder

brother Ernie, who was to become a top class welterweight, went their separate

ways: Ernie to a boys ranch and Danny to adoptive parents.

The youngsters kept in touch, and when Ernie started campaigning

as a professional in California, Danny decided that he too would be a boxer.

The strong right hand that was to account for so many opponents

in years to come rapidly attracted attention as the younger Lopez won a number

of Utah amateur titles. Then he joined brother Ernie in Los Angeles under the

astute tutelage of Howie Steindler. Ernie ‘Red’ Lopez would fall just short of

world championship glory. Danny ‘Little Red’ Lopez would go all the way.

Danny’s name quickly became synonymous with the Southern

California fight scene. He began his career in dynamic fashion as he racked up

three successive first round victories and won his next 18 fights by knockout or

stoppage. Japan’s Genzo Kuresawa became the first man to take him the distance

in early 1974.

Some of Danny’s early bouts were fiercely contested, and his 1972

win over the fiery Arturo Pineda was characteristically violent and short-lived.

The battle between the undefeated prospects filled the Olympic Auditorium in Los

Angeles, and featured three rounds of exciting slugging before Lopez struck with

the decisive punches in the fourth to register a dramatic victory.

A year later, Danny was involved in a similar brawl of rapidly

changing fortunes against Japan’s Kenji Endo. Floored and shaken by a hard right

from Endo in the opening round, Lopez rallied from near disaster to deck his

opponent just before the bell. In the second round, Danny continued to

demonstrate his excellent recuperative powers by scoring a further three

knockdowns to notch another epic win. As he moved up in class, Lopez learned the

age-old lesson that higher calibre opponents cannot always be despatched in such

quick and spectacular fashion. His points win over Genzo Kuresawa and a

subsequent tenth round TKO of Memo Rodriguez marked the beginning of a tough

1974 campaign, which saw his world title aspirations severely dented by the

defeat to Bobby Chacon.

Danny’s career seemed to waver uncertainly after that setback,

and his hopes of rebounding up the rankings were further damaged by two more

frustrating defeats. He knocked out Masao Toyoshima in three rounds but then

experienced a cruel stroke of luck in a gruelling fight with the rugged Japanese

battler, Shig Fukuyama. Danny was stopped in the ninth round after being

temporarily blinded by medication that had been applied to an eye cut.

Lopez then dropped a points decision to the skilful and

underrated veteran, Octavio ‘Famoso’ Gomez, but the positive aspect of these

reverses was that they probably taught Danny more about the tough trade of

fighting than most of his earlier triumphs.

He kept plugging away and was soon rolling again. Stoppage

victories over former world bantamweight champion, Jesus ‘Chucho’ Castillo and

Antonio Nava, followed by a sixth round knockout of Raul Cruz, were rewarded by

a golden match with the great Ruben Olivares for the North American title in

December 1975. The fading but still dangerous Olivares was looking to maintain

his status as a serious contender, having lost his WBC championship to David

Kotei just three months before.

Lopez idolised the legendary Mexican but was no less destructive

as he knocked out Ruben in seven rounds. It was an important victory for Danny,

one that confirmed beyond doubt that his career was truly back on course.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. It never was with Lopez. Olivares

was a 10 to 8 favourite and started with a rush as he decked Danny in the

opening round, in what many believed was a slip. Lopez blazed straight back and

sent Ruben tumbling just 30 seconds later with a short right. Danny kept firing

and knocked Olivares down for the second time with a left hook.

The Lopez bombardment continued in the second round, when Ruben

was caught by a combination of lefts and rights and hit the canvas for the third

time. But the old champion could still put on a show and he surged back into the

fight in the third, scoring with classy combinations to open a two-inch cut over

Danny’s right eye.

Lopez, however, in his own cliff-hanging way, controlled the

fight. A big right to the chin unhinged Olivares for keeps in the seventh round,

referee Dick Young counting out Ruben at the 1.59 seconds mark.

“Ruben was my hero when I was an amateur,” Danny later said.

“Beating him has to make a fellow feel like he had defeated Muhammad Ali. But I

am sure Ruben wasn’t what he once was. I have to admit I didn’t beat Olivares at

his peak.”

Unbeaten

In his next bout against the young and unbeaten Sean O’Grady, it

was Danny’s turn to play the role of the experienced campaigner against the

rising star. Lopez proved far too hard punching and resourceful for O’Grady,

recording a fourth round win at the Inglewood Forum.

Lopez was edging nearer a world championship confrontation with

Kotei. Danny’s vast improvement was evident in his revenge win over Octavio

Gomez in April 1976. Defending his North American crown, Lopez needed just three

rounds to dispose of Gomez, an exceptional result that earned ‘Little Red’ a

match with the chunky Canadian slugger, Art Hafey, in an official eliminator for

the WBC title.

Hafey was one of a group of colourful featherweights who added

excitement to the West Coast scene of the seventies, but Lopez confirmed he was

the best of them all as he produced another sparkling display of power punching

to stop Art in seven rounds. It was Danny’s 31st win in 34 fights and

the interest he had generated since turning professional had made him one of the

sport’s most colourful and popular fighters.

By contrast, David Kotei was still something of a mystery man,

despite his fabulous victory over Olivares. To all but the most studious of

boxing fans, the Ghanaian had seemingly come out of nowhere to jump to the top

of the division.

He had been unranked in some quarters when matched with Olivares,

yet Kotei had travelled to the great man’s favourite hunting ground of Los

Angeles and shown himself himself to be a strong, skilful and resilient fighter

in scoring an upset points decision.

Earlier in his career, David had not been overly impressive in

winning five and losing two of seven fights in Australia, but he had also shown

tantalising glimpses of his potential. He knocked out the hard punching Tunisian

Tahar Ben Hassan in one round to win the All-African featherweight title, and

took the Commonwealth crown from the tough and durable Scotsman, Evan Armstrong,

on a tenth round retirement.

The late Danny Vary, who worked Armstrong’s corner for the fight,

threw considerable light on Kotei’s talent, describing the young prospect as one

of the best featherweights he had ever seen.

Kotei subsequently proved that he was also good enough to hold on

to the world title. After dethroning Olivares, David twice successfully defended

the championship before taking on Lopez. Kotei displayed an effective jab and

threw damaging hooks and uppercuts to stop Japan’s Flipper Uehara in twelve

rounds in Accra, and then halted Shig Fukuyama in three rounds in Tokyo.

Although the Lopez camp was confident of victory against Kotei,

it was the defending champion who started favourite when the two fighters

stepped into the ring on the night of November 6, 1976. Any champion is tougher

to beat when he is fighting on home territory and Kotei appeared to be just

reaching his peak at the age of twenty-five.

Even though Lopez seemed to relish fighting under pressure, it

was generally believed that he faced too tough a task on this occasion; and so

it seemed as the first bell brought Kotei from his corner in express fashion.

Firing accurate punches from both hands, he surprised Lopez with

the suddenness of his attack, and Danny looked shaken as the champion’s bows

rifled through his guard. Lopez tried to rally and scored with several good

blows, but he couldn’t seem to avoid Kotei’s stinging jab and solid rights.

Kotei seemed intent on scoring a quick victory and continued to

gamble his energy in the second and third rounds as he maintained a fast pace

and punished Danny with hurtful jabs and right crosses. Lopez, never a fast

starter, was still trying to settle and seek a way past David’s jab. But the

challenger’s progress was thwarted by stiff counter punches whenever he moved

into range.

The puzzle was set for Danny and he could only charge on and try

to smash down the barricades. It was his style to go forward, whatever the

consequences. He began to enjoy some success in the fourth round as he bravely

walked through Kotei’s punches to score with his own lefts and rights.

But the strong champion continued to dominate the battle and

Lopez was struck by some fierce punches as he gamely tried to turn the tide. A

left hook opened a cut below Danny’s left eye and his chances of victory already

seemed to be receding.

In fact Lopez was in his element. One could almost see him

reaching for a can of spinach, like a desperate Popeye tied to the rail track.

The muscles flexed and the punches came faster with added steel as Danny dug in

and gradually battered his way back into the fight. Walking through the stiff,

spearing jabs of Kotei, Lopez forced the champion to retreat in the fifth round

as the balance of power began to subtly shift.

The sixth round was savagely fought as Lopez braced himself,

bulled his way through Kotei’s pounding jabs and engaged the champion in a

torrid slugging exchange. The drama heightened when a ferocious right hand shot

from Danny opened a cut on David’s right eyebrow.

Lopez erupted again in the eighth round, winging punches at Kotei,

while the ninth was another glorious showcase of both men’s courage as they

ignored the blood that ran freely from their cuts and stood their ground to

deliver vicious combinations.

Both men were concentrating their punches to the head as they

sought the decisive blows that would free them from the furnace into which they

had hurled themselves.

Maintaining his relentless pursuit of Kotei, Lopez was again

caught by solid blows in the tenth round. But he kept hammering away with his

own punches, trying all the time to trap the champion. Referee Harry Gibbs

cautioned Danny for careless headwork, as Gibbs had done twice before in the

earlier rounds, but in the main the slugfest was cleanly fought, for all the

blood and ferocity it exuded.

Stormy

Kotei was now going through a stormy phase and his task was

further handicapped when one of Danny’s punches split the champion’s lip. David

looked groggy in the eleventh round as he slipped to the canvas, and Lopez now

appeared to be in definite command as he kept up his pursuit of his wounded

prey.

Gamely, Kotei tried to match punches with Lopez in the twelfth,

but the challenger possessed the greater strength and won another important

round. Kotei was now desperately tired and Lopez swarmed into him in the

thirteenth round, hustling and punching all the time and winning the session

handily. Every round was packed with incident and suspense and now even the

minute intervals had their share of excitement.

At the end of the thirteenth, referee Gibbs asked the ringside

doctor to inspect Kotei’s cuts, and after a few tense moments the doctor ruled

that David was fit to box on. Then the interval was prolonged when the Lopez

camp noticed a split in Kotei’s right glove, and new gloves had to be laced on

the champion. The extra time might have helped Kotei had he not already expended

so much energy, but he still looked desperately weary and badly beaten as he

came out for the fourteenth round.

He showed immense heart in carrying the fight to Lopez, but now

the wavering champion’s punches lacked their former speed and power. Free of the

heavy pressure he had been subjected to in the earlier rounds, Danny was now

able to place his blows more accurately. He repeatedly jarred Kotei with precise

counter punches as the champion struggled to remain upright.

David walked slowly and painfully back to his corner at the end

of the round and one wondered how he could possibly endure the final three

minutes. Yet that certain feeling of pride and glory that comes from being a

world champion can lift the spirits of even the most tired and battered of men.

Kotei launched a final flurry in the fifteenth, one last hurrah

as his crown slipped from his head. It spoke volumes for his fortitude that he

was still willing to trade punches with a man who specialised in toe-to-toe

warfare. But the champion’s final fling could not match the power of Danny’s

grandstand drive to the finish line. There were moments in those last minutes of

battle when Kotei looked set to crumble in the face of the Lopez offensive, but

the plucky champion survived to hear the final bell.

The decision for Lopez was unanimous and the stunned thousands in

the Accra Sports Stadium were downcast over the sad fall of their hero. But

Africa is a warrior nation and the new chieftain was saluted accordingly.

The cheers that rang out for Danny Lopez were a mass salute to a

young man who had travelled so far and battled so hard to realise his dream; and

to an incredible fight in which two men of abundant courage had added another

memorable page to the glittering history of the featherweight division.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|