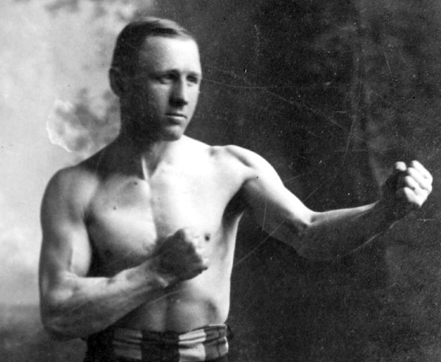

Blood, Guts And Greatness: The Incredible Kid Lavigne

By Mike Casey

Somewhat

reassuringly, perhaps the favourite indulgences of fight fans haven’t changed

radically down through the centuries. From day one, our curious and enduring

breed has adored the ritual of engaging in endless and inconclusive argument

that generally sweeps us straight up a back alley leading to nowhere.

More often

than not, it is impossible to prove our opinions or reach a definitive verdict

on what was the greatest fight and who was the greatest fighter. We just know

that it feels good to chase our own backsides when there is nothing much else

going on in the world. There is nothing quite so curative as a good old barney

with our favourite sparring partners. God forbid that they should come over all

magnanimous and actually agree with a single word we are saying.

Ad Wolgast

and Battling Nelson certainly started something back in 1910 after their

phenomenal battle of endurance at Point Richmond. Logically, Ad and Bat should

have been carted off to the cemetery after that one. It surely had to be the

greatest battle ever seen in the eternally fabulous lightweight division. The

cries of dissent were not long in coming – oh no it wasn’t!

Those of a

greater vintage argued that for sheer savage intensity, sustained excitement and

historical importance, there was nothing to match the brutal first battle

between George (Kid) Lavigne and Joe Walcott at Maspeth, New York, on December

2, 1895.

That fight

marked the thunderous arrival of Lavigne on the world stage.

Few men could

go head to head with Walcott, the great Barbados Demon, in a straight punching

battle for survival. But Lavigne, the young Michigan tornado known as the

Saginaw Kid, did just that and joined Walcott among the select ranks of men to

be feared.

It was a

fight that was already cooking long before the contestants got into the ring and

it established Sam Fitzpatrick as one of the shrewdest and most astute

matchmakers in the game. Lavigne and Walcott produced fifteen of the fiercest

rounds of fighting ever witnessed, their epic union cleverly engineered by

Fitzpatrick.

Walcott,

described by Nat Fleischer as “a short, thick-necked furious fighting man”, was

being managed by Tom O’Rourke and had compiled a mightily impressive record.

O’Rourke was able to provide Joe with constant training with the masterful

Little Chocolate, George Dixon. Walcott became such an accomplished and

dangerous fighter under the guidance of O’Rourke and Dixon that few people

doubted the Barbados Demon was the best lightweight in the world.

Around the

same time, Sam Fitzpatrick took Kid Lavigne under his wing. The Kid wasn’t

renowned for his love of training, but O’Rourke recognised the youngster’s class

and tremendous fighting spirit. Lavigne quickly progressed as he defeated tough

opponents in George Siddons, Jerry Marshall, Johnny Griffin and the tragic Andy

Bowen, who died from his injuries after the Kid knocked him out in eighteen

rounds in New Orleans. Lavigne also gained a highly creditable eight rounds draw

with the gifted drunken genius, Young Griffo.

Lavigne was

considerably under the lightweight limit and it wasn’t at all unusual for him to

give away significant weight to his opponents. However, such was his progress

that Joe Walcott and Tom O’Rourke grew more than a little annoyed with the

attention and praise being lavished on the Kid. Lavigne became as irritatingly

irresistible to them as a slippery salmon does to a hungry Grizzly Bear.

O’Rourke

couldn’t help but take the bait. It proved to be one of the few career blunders

that wise old Tom ever made. Not only did O’Rourke announce that Walcott would

fight Lavigne, but that Joe would agree to forfeit his entire purse if he failed

to stop the Kid inside fifteen rounds.

Sam

Fitzpatrick snapped up the offer but insisted that Walcott made the lightweight

limit. Walcott and O’Rourke readily agreed.

Fitzpatrick

took an iron grip on Lavigne in the run-up to the fight and insisted that the

Kid didn’t skimp on his training. Lavigne behaved himself and his conditioning

improved rapidly. Interest in the fight grew and betting was lively in the east,

where much money was wagered on Lavigne failing to last the agreed course. Such

was Walcott’s reputation as a wrecker of men that it was becoming increasingly

difficult for the Barbados Demon to secure matches.

Fitzpatrick

and a few of the Lavigne faithful countered by betting that the Kid would not

only last the distance but would defeat Walcott. Barbados Joe was supremely

confident that he would halt Lavigne and entertained no thoughts of losing.

Walcott stormed into the Kid from the start of the contest, but met with

terrific resistance as Lavigne hit back on even terms. Joe seemed taken aback by

the opposing force he had encountered, and the Kid’s tenacity didn’t diminish as

a gargantuan battle took shape and the rounds raced by.

Lavigne stood

toe-to-toe with Walcott through some withering, brutal exchanges, staying on top

of Joe all the time. One writer would later comment that the Demon had been out-demoned.

The pace of the fight was astonishing, as was the punishment suffered and the

injuries borne. The ring was stained crimson from the blood of both men’s

wounds. Lavigne would inherit a cauliflower ear from one of Walcott’s slashing

rights.

Incredibly,

the two titans didn’t seem to notice the outer limits to which they were

hurtling. Lavigne eventually outpaced Walcott to earn the referee’s decision

after a barn-burning battle of powerful hitting, courage and perseverance in the

face of terrible punishment.

Hooked

When Kid

Lavigne and Joe Walcott hooked up for their return match on October 29, 1897,

the Kid was the lightweight champion of the world and was repeatedly astonishing

the boxing public with the near frenetic pace of his attacking style and his

extraordinary toughness. It seemed that no man could hurt or deflect the

non-stop wonder from Saginaw.

Once again,

Lavigne proved Walcott’s master in mayhem, with Joe being pulled out of the

contest at the end of the twelfth round by Tom O’Rourke. The crowd of 10,000 at

the Occidental Club in San Francisco could scarcely believe how little effect

the tremendous blows of Walcott had on the relentless Saginaw Kid.

Walcott

entered the ring in his usual determined mood, adorned in a salmon-coloured robe

and attended by Tom O’Rourke, George Dixon and Joe Cotton. Lavigne was second

into the ring, his handlers including his brother Billy, Teddy Alexander and

Billy Armstrong. Billy Jordan was the master of ceremonies and Eddie Greaney was

the referee.

As in the

first battle between the two greats, Lavigne set a blistering pace and

maintained it. Walcott did extremely well to fight back and landed many a hard

blow when he was able to adequately time Lavigne’s rushes. But the Kid had taken

charge of the fight by the fifth round and Joe was unable to turn the tide

thereafter.

The seventh

round was one of the fastest seen by reporters of the day. Lavigne bulled

Walcott into the ropes and scored with a big left uppercut to the face. The Kid

followed with a right to the jaw that shook Joe badly and forced him to clinch.

Lavigne was merciless in such a situation and would just keep hammering at his

opponent. He wouldn’t leave the troubled Walcott alone and struck him again with

rights and lefts to the head.

Joe tried

desperately to summon all his ring smarts and weather the violent storm around

him, clinching whenever he could. But when he was sent to his haunches near the

ropes, it became apparent that he was living on borrowed time against the

rampaging little killer before him. Lavigne chased and harried Walcott all over

the ring in the eighth and ninth rounds, landing some thudding blows over the

heart.

Walcott

limped back to his corner at the end of the ninth round with muscular cramps in

his legs, a condition which often plagued him. His handlers worked on the legs,

but it was apparent to all that Joe required a major recovery and a big rally to

overturn the significant points lead that the charging Lavigne had compiled.

Walcott was

still limping when he came out for the tenth round, and his torment was only

worsened by repeated shots to the jaw that sent him staggering. By the twelfth

session, Joe was doing little more than surviving by calling on the last

reserves of his guile and instinct. The Demon fought with great gameness and

heart, but it was his heart that Lavigne continued to target with vicious and

well placed blows. By now Walcott was in no position to defend himself or fight

back effectively. When he returned wearily to his corner at the end of the

round, Tom O’Rourke told referee Eddie Greaney that the Demon could not go on.

Punishment

George (Kid)

Lavigne’s capacity to absorb punishment was so incredible that it seems almost

mythical to us now, much like the gruesome hardship and deprivation of his

savage era.

The stories

piled up about Lavigne and the evidence of their truth was in the footprints of

spilled blood, bashed bones, clotted noses and misshapen ears that led to his

door. In later years, as we shall see, the Kid spoke most humorously about the

grisly souvenirs he collected and their deceptively positive effect on his

well-being.

On October

27, 1896, Lavigne defended his lightweight championship against Jack Everhardt

at the Bohemian Sporting Club in New York. It was a fight that might be

described as par for the course in Lavigne’s turbulent and violent career. He

knocked out Everhardt in the twenty-fourth round, but the bare detail of such a

result could never hope to convey the full flesh and bones of a Kid Lavigne

punch-up.

Jack

Everhardt was a classy and educated ring mechanic and comprehensively outboxed

Lavigne for much of the way, punishing the Kid badly in the process. Lavigne’s

eyes were partially closed and his face was a swollen mess from all the

attention it received from Jack’s accurate punching. Finally, in typically

heroic fashion, the Kid caught up with Everhardt and knocked him out with a big

blow to the jaw. However, one found it difficult to tell the winner from the

loser. So badly battered was Lavigne that he had to be led from the ring after

his triumph.

The Kid had

already endured another taxing marathon after locking horns with Englishman Dick

Burge at the National Sporting Club in London on June 1, 1896. Lavigne had

gained recognition as the lightweight champion of the world with a dramatic

seventeenth round knockout of Burge, but Dick gave the Kid plenty to remember

him by.

Burge was a

conundrum. His brilliant talent was frustratingly offset by a Jekyll and Hyde

personality. James (Jimmy) Butler, the great British boxing reporter, wrote of

Dick: “His superb skill – for he was one of the cleverest boxers at his weight

the world has ever seen – kept Burge in the limelight for many years, yet he

always remained an enigma.

“Sometimes he

would box with a brilliance that would have won him a world title and sometimes

he would appear as lethargic and dull as any novice. You could never be sure how

he would shape.”

James (Jimmy)

Butler was a fortunate man who enjoyed some wonderful experiences in a golden

age. He never forgot a three-rounds exhibition he saw between Burge and the

legendary Jack McAuliffe in 1914. Burge had been out of the ring for fourteen

years by that time. McAuliffe hadn’t seen action in eighteen years.

Could they

still fight? Here is what Mr Butler wrote of their little set-to: “Those three

rounds between Dick Burge and Jack McAuliffe I shall never forget. The details

of so many of the big fights I have witnessed have long faded from my memory,

but the recollection of their marvellous exhibition is still vivid.

“Not for a

fraction of a second did they clinch. They stood toe-to-toe, as upright and

straight as poplars, feinting, leading, hitting, countering and

cross-countering, with a speed and skill that left us open-mouthed in wonder.”

Of Burge’s

fight with Lavigne, Butler commented: “Burge stepped into the ring a 2 to 1

favourite, but before the bout had progressed far it was evident that his

efforts to make the weight had left him weakened. The old snap and fire were

missing from his punch, and although he put up a desperate and plucky effort to

avoid defeat, it was of no avail.”

At one point

during that torrid battle, Lavigne mistimed one of his rushes at Burge and

charge headlong into a ring post. Typically the Kid regarded this as a minor

inconvenience, another honourable scar to add to his burgeoning collection.

Boxers As

Surgeons: The Kid’s Theory

Kid Lavigne

rarely felt bad about the lumps he took. Very often he was quite grateful for

them. They reinforced his intriguing theory that boxers could be as surgically

gifted as doctors.

Here is what

the Kid had to say about his bloody business: “You hear a lot about injuries

done in the ring, but you have never heard about the counter-irritant one blow

is to another, have you?”

Lavigne

pointed to his left ear, a classic cauliflower job of his era, and continued:

“Look at this ear that I’m carrying. It is a memory of one fight. My old pal Joe

Walcott gave it to me in our first fight and almost at the start of it. Some

people think that Walcott can hit. It got past the imagination place with me

before we boxed one round.

“I knew it

was true the first time he landed. And the first time he put one fair on this

left ear, he sent me back to my corner wondering if I’d ever forget that poke.

That was where I got my ear. In a round or two it puffed up and filled with

blood so that it looked like a raw tomato. It felt worse than it looked. There

was a whole comic opera chorus in my head, singing songs that sounded like the

music you hear in the dentist’s chair just before they wake you up.

“What would

have happened if Walcott hadn’t played surgeon for me, no one can tell. But

along in the fourth or fifth round, he brought his glove over on the bad ear,

pulled the heel across it and burst the ear. The songs stopped, the pain went,

the ear shrank and Mr Walcott was stopped in round fifteen.”

Walcott’s

‘surgical’ punch certainly had a deceiving effect on some reporters at ringside,

who initially thought they had seen Lavigne’s ear come off. Some time later, The

Kid was no less obliged to Dick Burge for a spot of skilful handiwork.

“Dick Burge,

the English fighter, performed another operation for me. It was the year after

the Walcott affair and Richard attended to my nose. Through being hit on the

bridge in other fights so many times, a little lump had formed. It wasn’t

painful, but it didn’t look pretty and it didn’t help me any in my breathing.

But I didn’t pay much attention to it until Burge and I got well warmed up in

our mill in London.

“The fight

went seventeen rounds and we hadn’t gone half of that route when Burge came to

me with a straight right on the nose that carried me part way to the sleeping

quarters. No one ever hit me as hard on the nose. I had to guess where my corner

was at the finish and I steered for it by the voice of my handlers. When I

cleared my nose, a thick clot of blood was discharged. That clot must have been

the lump that had been bothering me, and my nose was good as new when I went out

for the next round.

“I beat Burge

and he gave me a present of a straight nose to boot.”

No fighter,

however, played havoc with Lavigne’s nose more than the great but tragically

flawed boxing master, Young Griffo. The two men fought out two draw decisions,

which itself is testament to Lavigne’s class. Hitting the brilliantly gifted

Griffo was akin to trying to hit a ghost, irrespective of whether the alcoholic

Griff was sober (which was rarely) or drunk (which was often). Here was a man

who would keep himself in drinks later in life by spreading a handkerchief on

the floor of his local saloon, placing a foot on one corner and challenging any

man in the bar to punch him off it.

Here are

Lavigne’s recollections of the Australian maestro: “He was like a dozen arms. He

threw a hodful of arms at me every time I went after him. I’d start out and

would lead one that looked as if it ought to land and send the Australian over

the ropes. So far as I could see, Griffo never moved. But I didn’t see much, for

as soon as I led and started in, six or eight gloves would land on my nose and

knock my head back so that I was looking at the ceiling.

“He had my

neck in a hinge until the fight was about half gone, when I gave up anything

that seemed like boxing – just rushing wildly and trying to bear him before me.

I couldn’t hurt him much because he was too shifty, but he tired so that he

couldn’t stop to do any boxing himself – and that, when you had him throwing a

lot of gloves at you, was worth something.

Fighting

Fighting the

way he did, George (Kid) Lavigne was destined to wear down and wear out before

most others. He had been campaigning for just under three years when he lost his

lightweight championship in the blazing and defiant manner that one would have

expected of him.

The Kid’s

conqueror was the Swiss-born Frank Erne, a fast and clever ringman, who got his

big chance in his adopted hometown of Buffalo on July 3, 1899. The match took

place at the Hawthorne Athletic Club in the suburb of Cheektowaga, with Erne

capturing a 20-rounds decision in a lively and fast-paced battle. Both boys were

in terrific shape and the Kid started favourite.

While the

fighting was fierce between Erne and Lavigne, the duel was also shot through

with speed and skill from both combatants. In all the rip-roaring stories about

Lavigne, it is sometimes forgotten that the Kid was no slouch for ring

cleverness.

Certainly,

however, it was the Kid’s trademark courage that shone through more than

anything else in his last championship stand. He battled Erne on even terms for

the first six rounds, but things went awry for Lavigne in the seventh when he

ran into a hailstorm and received a bad lacing from Frank. The sound of the gong

probably saved the fading champion from being knocked out in that session.

Erne was

never quite so effective thereafter, unable to finish Lavigne. This was a puzzle

to many until it was discovered at the fight’s conclusion that Frank had badly

injured his left hand in that seventh round onslaught.

By the final

round, the Kid had been beaten virtually to a standstill by the precise punching

of Erne. Lavigne’s eyes were shut but he continued to chase Frank, even though

Erne’s punches were more plentiful and hurtful.

Lavigne’s

Greatness

George (Kid)

Lavigne was a natural and wonderful successor to the great Napoleon of the Prize

Ring, Jack McAuliffe. The Kid needed to be colourful and special to follow in

the footsteps of Jack.

McAuliffe had

ruled the lightweights when John L Sullivan bossed the heavies and Nonpareil

Jack Dempsey held sway over the middleweights. The three men were great friends

and referred to fondly by the American sporting public as the Three American

Jacks.

McAuliffe was

intelligent, possessed of great humour and loved the good life. His weight would

often be nudging 175lbs when he entered his training camp.

But Kid

Lavigne carved his own special reputation and did so magnificently. For a great

many years after his career was over, there were many boxing observers who

believed that Lavigne was the greatest of all the lightweights. Interestingly,

as late as 1944, by which time the career of Benny Leonard was done and dusted,

the debate as to who was the all-time lightweight king was not between Benny and

Joe Gans, but between Gans and Lavigne. Joe, the Old Master, got the majority of

votes. But the Kid claimed a healthy share of the poll.

But what of

Jack McAuliffe’s opinion on Kid Lavigne? Here are Jack’s thoughts on the Kid

from 1928: “Natural fighters always have had the better of book-made boxers in

the lightweight division, although Benny Leonard was one of the latter class and

he certainly fought his way up from a club fighter to a worthy champion.

“A natural

fighter, particularly a hitter, has the advantage. John L Sullivan was a natural

fighter. So was Jack Dempsey. I think Kid Lavigne was the greatest of them all.

I picked him as my successor when I retired undefeated and I made a good

selection.

“Lavigne’s

(first) fight with Walcott was one of the classics of the ring. The Saginaw Kid

had courage, stamina and was a natural fighter.”

McAuliffe

once fought a gruelling 64-rounds draw with a fighter called Billy Myer, who

carried the nickname of the Streater Cyclone. It is doubtful whether Billy ever

forgot Jack or vice-versa. Billy’s brother and near fighting equal, Eddie Myer,

certainly never forgot Kid Lavigne.

Eddie was

knocked out by the Kid in 1893 after taking a vicious right to the temple. Myer

was still suffering the after-effects of that punch thirty years later. In 1923,

Eddie did a little shiver as he told a reporter: “Often I can feel that blow

now, especially if I catch cold. Then the spot where he hit me gets sore and

aches like fury.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|