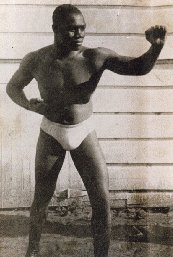

Sam Langford:

Papa Jack’s ominous shadow

By Mike Casey

What was it really like to have Sam Langford coming at you? On

March 17, 1910, at the Jeffries Arena in Vernon, California, Fireman Jim Flynn

got the answer to that question in painful, brain-scrambling fashion. So hard

and true was Langford’s knockout punch, so perfectly timed, that Fireman Jim

believed the fight was still on after his brief but ill-timed slumber. The

pugnacious battler from Pueblo could not be convinced that his business for the

day was done, even as a smiling Sam rushed around the ring and shook hands with

his well-wishers.

Dazed and disoriented, Flynn was set to hurl himself into another

frenzied attack at his tormentor when referee Charles Eyton told Jim he was out

and escorted him back to his corner. Reality took some time to penetrate Flynn’s

scattered senses. Gritty, proud and stubborn, the Fireman couldn’t conceive of

having his flames put out by Langford. Jim had drawn with Sam just a month

before in Los Angeles and had belligerently predicted a drubbing for the Boston

Tar Baby in their return. Now Flynn was sitting in his corner, getting the

terrible confirmation of the result from his handlers and feeling like a man who

meticulously plans a long journey and then somehow contrives to miss his train.

It was a masterful execution. A big right uppercut from Sam

dropped Flynn face down in the eighth round. The punch was expertly thrown. Jack

Johnson, Langford’s fellow legend and great rival, would fire the uppercut from

an upright position. Sam would twist his body in the appropriate direction and

somehow thread the blow through his opponent’s crossed forearms to the target.

Such was Langford’s sense of timing and commitment to the punch.

Up to the stunning coup de grace, the fight with Flynn had been

full of action and endeavour. Jim pressured Sam all the way, but it was

noticeable that Langford was considerably calmer and more measured as he looked

for openings. Flynn certainly provided a test for Sam’s analytical boxing brain.

When the Fireman wasn’t bulling forward and lashing away with wild blows, he was

causing some amusement with his curious defensive tactic of curling himself into

a ball like a hedgehog.

Langford in his best form was beautifully economical. He wouldn’t

throw a punch unless he was sure in his own mind that he could hit the target.

Here was a man who apparently had never had a formal boxing lesson, yet he

idolised Joe Gans and was arguably even more innately gifted than the Old

Master.

Jim Flynn’s face was soon bleeding and bruised from the attention

of Sam’s accurately placed jabs, hooks and uppercuts. Realising his best bet was

to stay close to Langford, Flynn would storm to close quarters and hook to the

ribs and the side of the body as he rested his head below his opponent’s chin.

Jim could use that head of his in more ways than one, as Jack Johnson would

discover two years later. Weary of being held in Jack’s vice-like grip in the

clinches, the shorter Flynn would comically take to the air as he repeatedly

jumped up and head-smashed Johnson to the chin. Watch the film of that old fight

and you will see Jack smiling wryly at livid Jim’s antics.

Langford knew he had Flynn. Countless stories would subsequently

be written of Sam’s apparent, uncanny ability to bring the curtain down at the

time of his choosing. Some such tales have inevitably strayed into the mythical,

but there is little doubt that Langford’s ability to read and dictate a fight

was exceptional.

In the seventh round, Sam slowed his pace and the largely

pro-Flynn crowd was deceived into believing that their man Jim was finally on

the upswing. In the words of the old song, Langford was simply reviewing the

situation. If Fireman Jim gained any comfort from Sam’s apparent lethargy, it

was short-lived. As the round drew to a close, Langford opened up again with a

succession of ripping and hurtful shots.

Boxing can be a cruelly deceptive sport. It can paint pretty

pictures and then deface them at the drop of a hat. Flynn looked just fine as he

set about his work in the eighth round. In fact he was better than he had been

all the way through as he chased Langford and found the mark with some hefty

body blows. Then Sam pulled the trigger. As Jim lowered his head to begin

another charge, Langford took one step back and launched the deciding uppercut

with a full sweep of his arm. The blow caught Flynn between his chin and mouth

and belted his world right off its axis.

Praise

The writers of Sam Langford’s day were lavish in their praise of

the Boston Tar Baby’s many talents. While we are all guilty of having a soft

spot for the fighters of our generation, it is true to say that the twinkle of

Langford’s star has not diminished with the passing years.

My good friend Curtis Narimatsu in Hawaii, who very kindly tops

up my vast collection of old fight reports with scrumptious clippings of his

own, has long identified Langford as a member of one of boxing’s most

significant triumvirates, along with Bob Fitzsimmons and the matchless master,

Joe Gans.

Says Curtis, “There is a distinct line of mentor influence

linking that stellar trio. Just as Gans idolised Fitz, so Langford idolised Gans.

Years later, in much the same way, Muhammad Ali would learn and improvise from

the technique of Sugar Ray Robinson.”

Broadway Charley Rose, the veteran boxer, trainer and manager,

saw them all up until his death in 1974 and would not budge on his choice of

Langford as the greatest fighter he had seen and among the elite of the

heavyweights. That is some compliment when one considers that Sam was never more

than a middleweight with lofty aspirations.

Rose said: “Sam Langford was the greatest fighting machine I have

seen. He could box, he could hit, he could out-think his rivals and display the

most consummate ring generalship the sport yet has seen.

“When Langford hit you on the button, there was no need to wait

and count over the fallen fighter. I remember when he stopped Al Kubiak in New

York. He belted Al with his famous right, and as Kubiak toppled, Sam left the

ring. He knew that the fight was over.

“Langford stopped Fireman Jim Flynn in Los Angeles virtually with

one punch. One of the local papers the next day said, ‘Fireman Jim Flynn got hit

on the chin. Amen’.

“Flynn had threatened to ‘malerate’ the Boston Tar Baby. Sam was

a great fighter in an era of great heavyweights.”

Writer Bill McCormack was also taken with Langford’s overall

prowess. In 1962, McCormack wrote: “Without doubt, Jack Dempsey was the most

exciting heavyweight – if not the most exciting fighter – the ring ever knew.

But I think the best of the big boys must have been Sam Langford. I know that’s

taking in a lot of territory, because Dempsey, Louis and Johnson were great, but

I have my reasons for liking the Boston Tar Baby.

“First of all, Langford made Lil Arthur (Johnson) run away and

hide. Johnson got the decision, by one means or another, when they fought in

Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1906, but never again could he be lured into the ring

with manager Joe Woodman’s squat fighting machine.

“Then, too, it was a well established fact that Sam was so good

he had to ‘put on the handcuffs’ before any of the big boys would take him on.

As it was, he licked Harry Wills in several of their numerous encounters, and

flattened Jim Flynn and Gunboat Smith when he was way past his prime.”

McCormack rightly pointed out that Sam was still a formidable

competitor near the end of his career when he was virtually blind.

“Perhaps the greatest thing Langford ever did was to flatten

Tiger Flowers in Atlanta in 1922. At the time, Sam was 44, Flowers 26.

“In the first round, Langford literally felt out the Tiger. He

had to. He couldn’t see him and had to locate him by feel. He came back to his

corner and notified his handlers, “This boy’s making mistakes. He makes ‘em

again and we go home’.

“Flowers made the mistakes and Langford knocked him out in the

second. Flowers went on to win the middleweight title from the great Harry Greb

in 1926.”

Natural

Langford was a pure natural. His physique, his brilliant boxing

brain and lateral thinking and his fistic versatility were all delightfully out

of kilter with textbook teaching. He thrilled the romantics and frustrated the

deep thinkers and number crunchers who despair whenever a Sam Langford cannot be

specifically filed and categorised.

Let us start with Sam’s incredible physique. In less enlightened

times, he was frequently compared to a gorilla. Such a yardstick might make some

of us wince with embarrassment now, but the comparison was well meant and

actually very apt.

For while Langford stood just 5’ 7’’, he was a physical

powerhouse. Broad shouldered and deep in the chest, he also possessed incredibly

long arms that consistently fooled opponents who thought they were out of range.

Sam was able to take full advantage of these physical gifts. His

speed in the ring was frequently described as ‘phenomenal’ and he was a

thunderous puncher. His stamina was never questioned and his boxing brain was as

sharp as that of Ray Robinson or any other fighter in history.

These talents gave Langford his career longevity. Starting out as

a featherweight in 1902, his last recorded fight was in 1926. He was going

steadily blind from 1917 and could barely see his opponents during the last days

of his career. He had turned 40 when he knocked out Andres Balsa for the Spanish

and Mexican heavyweight titles in 1923. Sam engaged in well over 300

professional fights, although it is doubtful that we will ever nail down his

exact total.

So fabled are Sam’s exploits as a giant killer of heavyweights

and light-heavyweights, it is often forgotten that he was a genuine all time

great in the middleweight and welterweight divisions.

Back in the late forties, a phony was posing as Sam Langford down

in Lexington, Kentucky. An eager sports writer delved into the story and found

the real Sam. The old champ was stone blind and just about getting by in a hall

room in Harlem.

Manager Joe Woodman had seen the disturbing signs years before

but couldn’t persuade Langford to quit. The successful partnership between the

unlikely pair was dissolved after Sam’s fight with Fred Fulton at Boston in

1917. Woodman recalled: “Sam got badly busted up around the eyes in that bout,

and I was afraid he’d go blind if he kept fighting. I told Sam he’d better quit,

but he was stubborn. He insisted he’d keep going. I said it was dangerous for

him, that he’d probably lose his eyesight and I didn’t want to be held

responsible. I argued and pleaded but it did no good. So we parted. I was right.

Sam did keep fighting and eventually became blind. It was too bad. He was a

great fighter and one of the finest chaps, personally, I’ve ever had anything to

do with.”

Joe Woodman was a licensed pharmacist by trade and was running a

drug store near North Station in Boston when his interest in boxing led him to

promoting fights at a small local club. There he took an interest in 16-year old

Sam Langford, who had travelled down from his home in Weymouth, Nova Scotia.

Young Sam was working in a brickyard at the time and wanted to fight

professionally. His relationship with Woodman would span 17 years and take them

all over the United States and Canada, and around the globe to England, France,

Australia, Panama and Argentina.

The living wasn’t always easy, as Woodman explained: “I don’t

know how many miles of land and water we covered, but I can tell you one thing:

it was long, often tedious travelling. There were no airplanes, you know, and we

had to go by train and ship. We were constantly moving. We didn’t stay too long

in any one place – just kept going to wherever we could get fights.”

Wills on

Langford

Whilst preparing for his 1924 fight with Luis Angel Firpo, Harry

Wills proudly told Damon Runyon: “I fought Sam Langford fourteen times and he

kept me down on the canvas for the full count but twice. Once, Sam stuck me away

in nineteen rounds and the other time in fourteen. I wasn’t in real good

condition either time.”

What Wills neglected to mention was that Langford wasn’t in the

greatest shape himself for the latter part of their ongoing series. The bare

statistics tell us that Harry decisively trumped Sam in the overall score, but

Wills was beating an ageing man whose eyesight was rapidly deteriorating. One

has to bear in mind also that the newspaper decisions of that era were not

always the most reliable of barometers.

Yet Harry was unstinting in his praise of Langford’s ability.

When it was suggested that Firpo was a dangerous puncher, Wills said, “He has a

good right hand but he can’t begin to punch with Old Sam. How that Langford

could crack you on the button! Just a twist of the wrist, and when you came to

your seconds would be dragging you to your corner.”

Harry Lenny, one of the great fight managers, pointed out that

the true one punch finisher is more of a rarity than many imagine. Langford, in

Lenny’s book, was one of the chosen few. “There are all kinds of punchers.

There’s the fellow who numbs you and the one who gives you a sharp shock.

“Joe Louis is what I call a bruising puncher. But he’s not one of

those one punch finishers He hit Max Baer over 250 times right on the whiskers

and still Max wasn’t unconscious when he was counted out on one knee.

“Jack Dempsey also was a crushing puncher, but it took a lot of

punches as a rule for him to finish a man.

“There have been very few one punch finishers in the ring. These

birds really are the terrific hitters. Sam Langford was that kind of a walloper

and there was a kid down in Baltimore years ago – George (KO) Chaney, a

lightweight – who could stiffen his man with one sock.

“When Langford hit you a short, sharp jolt, the lights went out

on you and that’s all there was to it.”

In the early years of the twentieth century, Langford was one of

a famous and celebrated quartet of black fighters. Jack Johnson, Joe Jeannette

and Sam McVey were Sam’s greatest rivals, but in truth only Johnson was on the

Boston Tar Baby’s special level.

When Sam decisioned Joe Jeannette over 20 rounds at Luna Park in

Paris in December, 1913, correspondent Stephen Black drew attention to the

marked differences between the two men in their talent and general demeanour.

“Jeannette fought like a greyhound, a plucky greyhound that wants to fight but

can only fight his own way. As he retreats, he snaps back little biting snaps

that worry the other fighter unless he is a thoroughbred bulldog like Sam

Langford. For that is exactly what Langford is in appearance and by temperament.

He is a bigger edition of Joe Walcott, the black demon, and I think a better

one.

“Jeannette looked worried in his corner before the beginning,

whereas Langford sat up waiting for the bell like a bulldog expecting a bone.”

Greatest

fighter

Jack Blackburn, legendary trainer of Joe Louis and a formidable

lightweight in his day, offered the opinion that Sam Langford was the greatest

fighter of all. Plenty of Jack’s contemporaries concurred with that opinion.

In his wonderful book, ‘Kings of the Ring’, British boxing writer

James ‘Jimmy’ Butler, said of Langford: “I set him down without hesitation as

the greatest glove-fighter I ever met. I still think that had he been matched a

second time with Jack Johnson, he would have beaten the champion.”

Butler was at ringside for Langford’s fight with the big

Australian Bill Lang at Olympia in London in 1911. The record book has been kind

to big Bill, as it shows that he lost the bout on a sixth round disqualification

after whacking Sam on the chin while he was on one knee from a slip. This masks

the fact that Langford gave Lang an almighty thrashing up to the unfortunate

conclusion. The 210lb Lang had outweighed Sam by nearly 50 pounds.

Lang’s mentor, newspaper magnate Hugh D McIntosh, couldn’t

believe what he saw. Before battle was joined, he had raved about his white hope

to Jimmy Butler and said, “He’ll eat this coloured boy, Jimmy – just eat him.”

Oh dear.

During Sam’s visit to London, he told Jimmy Butler, “I’m not the

champ. Jack Johnson is that guy and he keeps dodging me.”

Butler subsequently wrote: “That, as a matter of fact, was the

plain and unvarnished truth. Johnson did dodge a meeting with the Boston Tar

Baby after their terrific clash at Chelsea, Massachusetts.

“Johnson just scraped home on points after fifteen rounds, but I

think he learned enough to realise that if he ever got into the same ring with

Langford again, those gigantic arms and shoulders would make short work of

sweeping him off his throne.”

Well, there is little doubt that Johnson did indeed steer a wide

berth of Langford after their one and only confrontation. But did Sam really

give Jack such a close call in that Chelsea fight? The rumour persisted for

years that Langford had even decked Papa Jack, which offended Johnson greatly

and prompted him to issue a series of vehement denials.

In an open letter to The Ring magazine in 1934, Johnson wrote: “I

have accounts of the fight from my dear old friend, Tad (legendary sports writer

and cartoonist Tad Dorgan) which show how badly Sam Langford was whipped. Please

note the account of our fifteen-round fight at Chelsea, Mass., which I am

enclosing. The report shows that I gave poor Sam such a severe trimming that he

had to find his way into a hospital to recuperate. The records of that fight

prove that statement to be correct.

“Langford was among the five fighters to whom I gave the worst

beatings in all my career. This quintet was composed of Jim Jeffries, Tommy

Burns, Sam Langford, Sailor Burke and Frank Childs.”

To his dying day in 1972, Ring editor Nat Fleischer maintained

that Jack Johnson was the greatest of all the heavyweights. Understandably, Nat

was eager to get to the bottom of the Johnson-Langford controversy. In his 1958

book, ’50 Years at Ringside’, Fleischer produced the testimony of his

father-in-law, Dad Phillips, who allegedly saw the fight.

Said Phillips: “Jack Johnson decisively defeated Sam Langford. He

was complete master of the situation. Jack so far outclassed Langford that for a

time, until he purposely eased up on his onslaughts, the fight was one-sided.

“Langford was dropped twice for counts of nine, and he would have

been out the first time if referee Martin Flaherty had not slowed up the count.

At the end of the fight, Sam had to be taken to a hospital.

“As for Langford dropping Johnson, that’s absurd. Why, he

couldn’t land on Jack.”

Sam’s alleged knockdown of Jack continued to bug Nat Fleischer,

who had to find the truth from the nearest equivalent of the horse’s mouth. Nat

cornered Langford’s former manager Joe Woodman and good-naturedly demanded the

true version of events.

According to Fleischer, this was Woodman’s response: “You’ve got

me, Nat. Langford never dropped Johnson. But I was anxious to fix up another

fight between the two and, knowing Jack’s pride, I invented the story of that

knockdown to goad him into the ring against Sam again.

“Although it never happened, all the newspapermen believed it.

They just never took the trouble to investigate. That knockdown was just a

publicity gimmick.”

Well, we take all that for what we will. The simple fact is that

only the long dead players and supporting cast from that gloriously mystical

fight at Chelsea knew what really happened.

Sam and Stan

The National Athletic Club in Philadelphia had never known the

like of it People came from all over the country. There was a special train of

six cars from New York and large parties from Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Washington,

Cleveland, Cincinnati, Boston and other major cities.

It was April 27th, 1910, and Sam Langford was locking

horns with Stanley Ketchel. The two titans of the game would wage a six-rounds

no contest, but the short-lived bout was still worth the miles and the money to

those who came.

The myth of this set-to was that it was little more than an

exhibition. It was much more than that. It was a thrilling fight in which both

gladiators fought viciously. After a quiet first round, Sam and Stan set about

seeing what they were made of. Ketchel attacked Langford’s body with ripping

hooks, only to be met by sledgehammer jabs and powerful right uppercuts.

At the end of the third round, a hard uppercut from Sam brought

blood streaming from Stan’s nose, angering the Michigan Assassin and causing him

to swing wildly.

The tide turned in the fourth when Ketchel shot a tremendous left

to Sam’s body. The blow closed Langford’s eyes momentarily and forced his mouth

to drop open. The bell prevented Ketchel from doing further damage.

Sam had Stan’s nose bleeding again in the fifth round, but had to

withstand a hard right to the jaw for his troubles. Canny Ketchel was staying as

close to Langford as he could, but a steaming uppercut from Sam in the sixth

lifted the Assassin off his feet. Incredibly, Ketchel kept coming, although he

seemed to be slowing at the finish as his nose bled heavily and stained his body

crimson.

There were those who believed Sam had the edge by the close of

battle. Others disagreed. There had to be a return match, but fate cruelly

prevented it. Six months and three fights later, Ketchel died from the bullet of

another assassin who came in through the back door.

Sam Langford, of course, just kept rolling along. Ye gods, what a

pair!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|