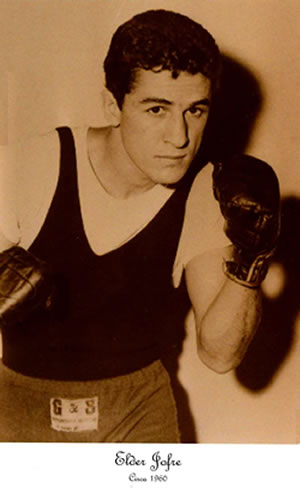

Genius with

the Samba beat: Golden bantam Eder Jofre was the complete fighter

By Mike Casey

When it finally happened, nobody could quite believe it. Eder

Jofre had been beaten. It didn’t seem possible and people had begun to wonder if

it was even allowed.

Far from the sun-kissed shores of his native Brazil, before

12,000 wildly cheering Japanese fans at the Aichi Prefectural Gym in Nagoya, the

masterful genius of a boxer who could do it all had lost his bantamweight

championship to the perpetual little buzzsaw that was Masahiko ‘Fighting’

Harada.

News of such cataclysmic events took an age to trickle through to

the average boxing fan in the stark and simpler days of 1965. There was no

Internet, no twenty-four hour news stations and no mention of boxing on the TV

or radio unless Muhammad Ali had done something else to ruffle the feathers of

the silent majority.

When I finally saw the result in the newspaper, tucked away at

the bottom of the page in the form of a two-liner, I seriously wondered if the

sub-editor had lunched for a little too long at his favourite watering hole and

accidentally transposed the names.

Nobody expected Eder Jofre to lose to Fighting Harada, because

Jofre was a genuine wonder of a fighter who didn’t lose to anyone. Not since the

days of Panama Al Brown and Manuel Ortiz had a bantamweight champion looked so

dominant or stood so toweringly over his peers. Eder had mastered his division

with such a sublime and disciplined combination of skilful boxing and

brilliantly timed power punching that old and new sages alike were hailing him

as a Sugar Ray Robinson in miniature.

There didn’t seem to be an element of the game at which the

Brazilian didn’t excel. As well as skill and power, Jofre was one of the ring’s

great thinkers who combined excellent speed and timing with almost saintly

patience. A tall man for a bantamweight, he never looked awkward or gangling in

the semi-crouch from which he plotted and fired his artillery. Ever jinking,

bobbing and weaving, he was able to co-ordinate his thoughts and actions

seamlessly and with devastating effect.

It was Eder’s preference to play a chess match with his opponent,

assessing the other man’s strengths and weaknesses and drawing his early fire

before beginning the systematic process of breaking him down. But if the game

plan went awry and an old-fashioned fight was called for, Jofre was no less

efficient at biting the bullet and winning through. He possessed an uncanny

ability to adapt and re-invent his style in the heat of battle, as his cool

brain worked out the logistics and formulated the appropriate game plan. Of all

the men who have held the bantamweight and super-bantamweight crowns since, only

the prime Erik Morales has shown this writer such comparable versatility.

Before the sensation against Harada in Nagoya, Eder Jofre had won

forty-eight and drawn two of his fifty fights and had seen off such sterling

challengers to his throne as Piero Rollo, Ramon Arias, Johnny Caldwell, Herman

Marques, Jose Medel, Katsutoshi Aoki, Johnny Jamito and Bernardo Caraballo.

But the great man was wavering over his future, which was

probably his undoing. Jofre could see the finishing line and funny things happen

to even the greatest athletes when they hit the home stretch and race for the

wire. They suddenly stop doing what comes naturally as the urge to bask in their

glory takes hold. Jofre was undefeated, a sporting god of sorts and a hero to

the Brazilian people, who paid him homage in much the same way they worship

their sacred soccer players. There was no fighting man alive like their ‘Jofrinho’.

The stage was perfectly set for Eder to retire and cement his legend as the

great invincible. But then he began to talk about it, as fighters do. Before the

final obstacle had been hurdled, he let it be known that he had other things on

his mind.

Masahiko Harada was a furious fighting man, a former world

flyweight champion who had moved up to hunt bigger game, but he was accorded

little chance of defeating even a distracted Jofre. Most of those in the know

reckoned that the Japanese warrior, for all his fire and fury, would be picked

apart and dismantled inside five rounds.

The fight was a storming and exciting affair, in which Harada was

fearless and relentless in his attacks. Jofre had gone to Japan to find one last

dose of glory. Instead he found his nemesis. Eder’s studious, reconnaissance

mission of the early rounds, the foundation on which he built his brilliant

work, slowly turned to quicksand against this whirlwind of a challenger. Harada

was tireless, punching all the time, a man who saw his big chance and believed

he could grasp it. Jofre had always found a way of handling such impudent

pretenders. Like an expert angler outsmarting the canny and slippery marlin, he

would give them so much line and then reel them in. But this man Harada was

something else, the Aaron Pryor of his era in his ferocity and sheer

persistence. He was chewing up the line and he wanted to eat the angler for good

measure. Jofre sacrificed the early rounds in his attempt to analyse and compute

his feisty challenger, a deficit he would never claw back. Eder was caught in a

storm and the gifts that the gods had bestowed upon him were suddenly being

snatched back. Never had his defences been so penetrated as Harada found his

chin repeatedly with rapid-fire shots. Like any great king who has reigned

unvanquished for so long, Jofre’s mind couldn’t seem to accept that time was

running out. He jabbed, he countered effectively with vicious punches, but never

with sufficient urgency or consistency. He was waiting for that inevitable

moment when his magic would make his challenger turn to dust. That moment never

came.

Harada crossed the line to win a split decision and was suitably

modest and sporting in the afterglow of his wonderful achievement. “I was lucky

to win,” he said. “It was a very close fight. I was fighting hard all the time.

If the boxing authorities believe Jofre is entitled to a chance to regain the

championship, and he wants that chance, I shall give it to him.”

While the deflated Jofre was left to mourn the glorious

retirement that never was, his manager Abraham Katzenelson dutifully excused

him. Abe protested before and after the match about the Japanese gloves and had

tried to import a pair from Mexico. The Japanese gloves, he argued, were too

rough. But when was anything too rough or tough for the great Eder Jofre?

True to his word, Harada gave Jofre his return a year later in

Tokyo. But the writing was on the wall for Eder six months before, when he was

held to a draw by the tough Manny Elias in a tune-up fight in Sao Paolo. The

genie had escaped the bottle, the magic was gone. Harada beat him unanimously

and that was that. It was the spring of 1966 and the great career of Eder Jofre

was over after fifty-three fights. Or so it seemed.

Gym

When a young boy is raised in the back room of a boxing gym, he

is going to spend his life either loving boxing or hating it. Eder Jofre loved

the game and yearned to be a great fighter. Standing before a mirror, he would

imitate the world class boxers he had seen and religiously practice every aspect

of his chosen discipline. Studious and serious, he made excellence his

benchmark. He couldn’t abide anything less and worked like a demon to expunge

any weaknesses from his make-up. So many naturals of the sport waste their

talent because they never fully grasp its rarity or significance. What made

Jofre special was that he appreciated the value of the precious diamond in his

locker and still wanted to heighten its gleam.

His progress was impressive when he graduated to the professional

ranks in 1957. Eder won ten of his twelve fights that year, showing early

flashes of the power and grace that would enable him to cut a swathe through two

weight divisions. His early progress was checked by a couple of draws with

Argentina’s Ernesto Miranda and a stalemate with Ruben Caceres in Uruguay. One

could imagine the meticulous Jofre making a mental note of those two names for

his further attention.

The Brazilian maestro ploughed through everyone else as he

registered the first notches on a knockout tally that would reach 50 by the time

he had completed his nineteen-year, 78-fight career. He quickly proved that he

could overcome adversity, bouncing back from his first knockdown as a pro to

stop the capable Jose Smecca in seven rounds in 1958. Eder met up with Ruben

Caceres again in 1959, leaving no doubt as to who was the superior man as he

knocked out Ruben in nine rounds.

Jofre was on the cusp of his first wave of greatness, and

emphatically stamped his class on the division in his glittering campaign of

1960. He settled his unfinished business with Ernesto Miranda with two

successive victories for the South American title and then waged one of the

great modern bantamweight wars with the dangerous Jose ‘Joe’ Medel at the

Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles in August.

Medel was a highly accomplished ring mechanic. Cagey, cunning and

a very hurtful puncher, the Mexican ace was a stalwart contender among the

quality bantamweights of the sixties. He simply had the misfortune to share his

prime fighting years with Jofre and Fighting Harada.

But Medel claimed plenty of other top scalps. Coming into the

Jofre fight, Joe was fresh from winning the Mexican bantamweight crown from Eloy

Sanchez, who would cause such a sensation in his next fight by ending the career

of world champion Jose Becerra on a shocking eighth round TKO.

Medel tried everything he knew against Jofre in a terrific,

thrilling duel of power and wits. Both men were showing the marks of battle when

Eder brought the curtain down in the tenth round with a perfectly timed right

cross to the jaw. Eder was already establishing his ability to assess and defeat

opponents of any style. He could outbox the boxers and outpunch the punchers.

Few bantamweights at that time could punch as hard as the wildly unpredictable

Ricardo ‘Parajito’ Moreno, who was swept aside in six rounds just a month later.

Jofre’s coronation was imminent. It had been his ambition to

challenge the big punching champion Jose Becerra, but Eloy Sanchez had scuppered

that plan by wrecking Becerra in their non-title engagement. The change of tack

made no difference to Eder, who thrilled the fans at the LA Olympic once again

as he secured the vacant NBA title with a ripping knockout of Sanchez in an

exciting fight. Jofre’s growing universal appeal was easy to appreciate. Clever

and shrewd operator that he was, his style was laced with just the right dash of

vulnerability to make his dominance lovable rather than merely respected.

Sanchez so nearly grabbed the glory from him in the concluding sixth round when

he knocked the Brazilian’s mouthpiece out with a terrific blow. But Jofre always

seemed inspired by such a test of his character and once again his slashing

right cross ended matters with dramatic suddenness.

Just as every picture tells a story, so Jofre’s fights were

becoming vibrant and colourful vignettes that lingered in the memory. There was

always something to admire, something to cherish, something to make the blood

tingle. The appeal of the little magician from Brazil didn’t require time to

ferment and mature in the minds of those who sit in judgement. It was gloriously

immediate and pulsating. Former champions like Barney Ross came in praise of

him.

Vicious

When Eder gained universal recognition as bantamweight champion

in January 1962, before his adoring fans in Sao Paolo, it was with a singularly

vicious and systematic destruction of game Irishman, Johnny Caldwell. Johnny’s

confidence was given a nice little boost when he won the opening round, but

Jofre had now reached the point of near perfection where he could step up to a

level that was simply beyond the reach of his opponents. Whatever tricks the

other man had, Jofre had more. And he could perform them with bewildering

dexterity. He rifled Caldwell with jabs and broke him down steadily with

creasing left hooks. Johnny fought his heart out as any good Irishman does, but

he was floored twice and badly bloodied before his manager had seen enough with

seconds remaining in the tenth round.

Eder was heading for a return match with Jose Medel, which was

eagerly anticipated by knowledgeable fight fans. We say so often how perennial

contenders of the past would now be champions in today’s more accommodating,

multi-title ocean. Sometimes, of course, we exaggerate. Certain men would have

been perennial contenders in any era because of some unfathomable mental chink

in their armour. Yet there is a very valid case for saying that Jose Medel would

be sitting atop some kind of alphabet throne today in the absence of the

Brazilian shark that kept coming to feast on him.

For all his considerable talent, Medel simply couldn’t live with

Jofre in their return go. Eder was at the top of his game and, incredibly, still

looked capable of improving. He used the opening rounds to gauge the resistance

his Mexican challenger and then went to work with the flashing jabs and fast

hooks that his challenger couldn’t stop or simply couldn’t see coming.

With beautiful movement and subtle turns of his head, Jofre

almost casually avoided most of Medel’s return fire. The tough man from Mexico

was all in by the end of the fifth round when he was sent to the canvas for the

first time. Jofre lowered the boom in the sixth with a peach of a right to the

jaw.

Jofre’s dominance of his division was now so emphatic that his

vanquished opponents could only sing his praises in the after shock of their

destruction. When Katsutoshi Aoki had his early points lead brutally wiped out

by Jofre in Tokyo in the spring of 1963, the shell-shocked Japanese star

commented, “I felt the first knockdown wallop. But I still don’t know what hit

me when he knocked me out. That man has a terrific punch.”

What hit Aoki was not Jofre’s pet right, but a pair of awesome

left hooks that stunned the Japanese crowd into silence. Up to that point, the

fearless Aoki had been hurting Eder with his brazen attacks, punching away at

the mildly flustered champion and no doubt dreaming of championship glory. The

sound of the crowd was deafening as the cheers and yells of Aoki’s supporters

echoed around the Kurame Sumo Arena. Their joy lasted for two minutes and twelve

seconds and then they were heading for home.

Greatness

Simple black and white, with its many shades and subtleties, can

be so much more devastating than colour, as any good photographer will tell you.

As a boy, I loved those pictures of my favourite fighters that showed them

either partially obscured or lurking menacingly in a certain light. It added to

their mystery and fired my imagination.

I saw one such picture of Eder Jofre in 1964, in which he was

dramatically silhouetted by a single steak of light as he moved in for the kill

on Colombia’s talented Bernardo Caraballo. In white letters above the picture

was the simple heading, ‘Greatness in our time’.

Jofre was knocking out Caraballo in the seventh round after

tormenting and deceiving his nimble and talented challenger for the previous

six. Caraballo, like so many before him, must have believed he was about to

crack the great Brazilian nut. He had reddened Jofre’s forehead and nose, shown

impressive footwork and had put his punches together well. He was unbeaten in

forty-three fights and fighting before his hometown fans in the intimidating

atmosphere of the Nemesio Camacho Stadium in Bogota. Then the roof fell in and

the game little challenger could only sob in his dressing room afterwards. “I

did my best,” he said between tears. “It was not enough.”

Who could beat this genius Eder Jofre? That was the question

everyone was asking before the great shock in Nagoya against Fighting Harada.

Yet the shattering of Eder’s air of invincibility would prove to be a curious

twist of fate. Far from diluting his greatness, it would ultimately strengthen

it. Thirty-three months had passed since the second Harada defeat when Jofre

suddenly came back to win a decision at featherweight over Rudy Corona. Nobody

paid much attention. Eder was thirty-three, a dangerous age for a man of his

weight, and seemed to be treading the sad and inevitably disappointing path of

so many old fighters before him.

But this old fighter just kept rolling and winning.

Astonishingly, the Brazilian ace was about to do it all again. He scalped

fourteen opponents before winning the WBC featherweight championship from Jose

Legra at Brasilia in May 1973, yet retirement still wasn’t on the great man’s

mind. He was the old Jofrinho again, perhaps no longer as devastating or as

downright mean in the violence of his attacks, but still too hot for the young

guns to handle.

Clearly revelling in his new lease of life, Eder scored quality

wins over Godfrey Stevens and Frankie Crawford and followed up with a successful

title defence against fellow great Vicente Saldivar. Sadly, the WBC spoiled the

comeback party by stripping Jofre of his title, and one had to wonder if Eder

was being mischievous by sticking around to win a further seven fights before

finally calling it a day. He was thirty-seven when he outscored Octavio Gomez in

the last hurrah in 1976.

Greatness in our time? Oh yes. Very definitely so in the case of

Eder Jofre.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|