Hit Me With

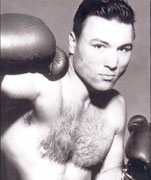

Your Rhythm Stick: Joe Grim and George Chuvalo

By Mike Casey

Armed with a Louisville Slugger apiece, Joe Grim and George

Chuvalo are in some kind of heaven, though it isn’t a place of angels and

harps. Chuvalo swings his bat hard into the pit of Grim’s stomach and Joe

laughs at him and says, “Nah, you gotta hit me harder than that to hurt me,

George. Now you try bouncing one offa my jaw.”

“Nah, it’s my turn now,” Chuvalo protests. “Smack me one over the

head. I betcha I don’t even blink.”

Down through the corridors of time, boxing has spawned some

remarkably tough and resilient men. Joe Grim and George Chuvalo, who fought in

vastly contrasting eras, were very definitely two of the toughest. While the

more technically inclined exponents of the game were inflicting traditional

damage in the way of cut eyes, broken noses and sore ribs, Joe and George were

thinking laterally and leaving a trail of bruised fists and dented egos. Two

generations of fearsome punchers walked away in amazement after vain attempts to

knock out the defiant duo. Breaking rocks in the midday sun was more fun than

trying to break Grim or Chuvalo.

Both men plied their trade in the shadow of great world

champions. Grim wanted nothing more than to beat the mighty Jim Jeffries, even

though Joe didn’t often beat anyone else. Chuvalo tracked Muhammad Ali, warming

up for the challenge by severely hurting the knuckles of Ernie Terrell and Floyd

Patterson.

It was the mental scars meted out by Grim and Chuvalo that hurt

their conquerors the most, compelling them to try and make sense of it.

Patterson would say of George, “I hit him several times with punches that would

knock other people down. But he didn’t go down.”

Floyd, who could be quite scholarly about such things, added that

other men’s brains tend to cut out and go to sleep after being hit hard. Not

Chuvalo’s brain. George just cocked a snook at biological logic. He would have

loved Joe Grim.

It was Joe who took a ferocious pounding from Jack Johnson over

six rounds before sticking out his tongue at the finish and calling the

Galveston Giant a bum. Jack shook his head at his cornermen and said, “I just

don’t believe that man is made of flesh and blood.”

The tributes flooded in for Joe Grim, just as they would flood in

for George Chuvalo some sixty years later. Tributes that were very different

from the norm. Of Grim, Irish Joe Thomas would say, “You might as well hit a

sandbag.” Chuvalo would be compared by the Associated Press to a man being paid

piece work for the number of punches he could take.

An Italian iron man and a Canadian rock. That was Joe Grim and

George Chuvalo respectively. It would make a nice little supernatural twist to

our tale if we could say that tough Joe, who died in 1939, came back as tough

George. Alas, Chuvalo was already toddling around as a two-year old by that

time, no doubt causing significant structural damage to the walls of his home

whenever he bumped his head.

Man, oh man, did Mr Chuvalo and Mr Grim have hard heads. When Joe

was a young boy in Italy, he had a novel way of earning money from tourists.

Much more inventive than his contemporaries, the rugged youngster didn’t opt for

the boring business of showing visitors the beauty spots or tipping them off on

the best places to eat. For a silver lira or less, he would demonstrate his

mettle by running headlong into the iron door of his local church. Joe’s face

would balloon with various bumps and bruises as his act became a regular

feature, but his friends would recall in amazement how he would never be so much

as dazed. History does not tell us how many tourists were impressed by this

curious act of masochism or how many were forced to scoot behind the nearest

tree to bring up their breakfast.

America

When most folks come to America in search of their dreams, they

are looking to buck the odds and not be beaten down. Joe Grim, with typical

perversity, openly invited America and her best fighters to beat him into the

ground.

He had been born Saverio Giannone on March 16, 1881, the eighth

of nine children, but quickly learned that the fast and urgent world of America

didn’t have much truck with complicated names. Joe Grim was easy to pronounce in

a land that had yet to become more multi-culturally diverse.

Joe went to work as a bootblack and had a little stand near the

Broadway Athletic Club in Philadelphia. He loved boxing and spent his evenings

sitting in the ten-cent seats in the gallery watching the fights. His loyalty

and enthusiasm paid off one night when the management asked for a volunteer from

the audience to substitute for a fighter who hadn’t shown up. Joe jumped at the

chance and soon showed the stunned audience what he could do. For one thing, he

could fall down many times from thunderous blows to the head and body and keep

getting up without taking a count. Much as he loved his boxing, Grim was utterly

ignorant of its subtleties and technicalities. He simply couldn’t fight in the

traditional sense.

What made him additionally remarkable, however, was that he was

never cursed with a loser’s mentality. He tried his utmost every time, bragged

unashamedly that he would knock his opponent out and quite genuinely believed

that he would do so.

Joe became an instant hit at the Broadway Athletic Club for his

astonishing courage and comical antics. He would smile and chuckle all the time

as he bounced up from shuddering knockdowns like a mischievous rubber ball. Club

promoter Lew Bailey was soon managing him, impressed by Grim’s equally shining

talent for marketing himself to his adoring faithful. After every hideous

thrashing, Joe would make a speech in which he would throw out a challenge to

world champion, Jim Jeffries.

Big Jeff, in his delightfully sober way, became convinced that

this little fella Grim, all 5’ 7” and 50lbs of him, was a plain and simple

madman. Even Sam Langford didn’t want to fight Jeffries and Sam could actually

fight.

Undeterred, Joe Grim ploughed on, his fame spreading like

wildfire as the larger boxing clubs began to employ his very special services.

He was never short of willing opponents. While the astute Jeffries had the good

sense to steer a wide berth of Grim’s carnival, plenty of other marquee names

couldn’t resist the insatiable urge to massage their egos and try to knock out

the man who simply wouldn’t be flattened. Champions and contenders who should

really have known better became obsessed with the challenge of becoming the

first man to put Joe Grim down for the ten count. Joe Gans, the brilliant Old

Master, tried with everything he had in ten brutal rounds with Grim at Baltimore

in 1904. Gans didn’t do too badly, breaking only three of his knuckles as he

knocked Grim down 17 times. But the Italian wonder was still there at the end,

mocking the maestro’s punching power and even having the cheek to criticise his

stance. How must poor Gans have felt? Much like Picasso being asked by a man on

the street, “Are you the guy who paints them rinky-dinky pictures of funny

shapes?”

Peter Maher, by contrast, could only have felt like going home

and drinking himself into oblivion. Perhaps, indeed, he did. Thunderous-punching

Peter not only failed in his quest to knock Grim out at the Industrial Hall in

Philadelphia, but also committed the cardinal sin of getting knocked out

himself. Dozing fighters have been known to get stiffened by their punching

bags, but certainly not punching bags that have mouths and can brag about it.

One simply cannot draw a quiet veil over those occurrences. Fortunately for

Peter, Grim’s desperation wallop was a right uppercut that began its journey

from the floor and was still south of the border when it crashed into Maher’s

wedding tackle and sent him down.

As a witty reporter of the time noted: “Peter then thoughtfully

yelled foul and made a blind stagger to his corner.”

Grim was disqualified in one of his rare moments of positive

glory and Maher’s blushes were at least spared to a degree.

Many other illustrious names tried their best to wipe the cheeky

smile off Joe Grim’s face and put him into a slumber, including Philadelphia

Jack O’Brien, Barbados Joe Walcott, Dixie Kid, Johnny Kilbane and Battling

Levinsky.

Jack Blackburn, he of the lightning fast hands and withering

punching power, should have been given a gold medal for blind perseverance. In

three successive bouts, Jack went through the formidable tools of his arsenal

and failed to knock Grim into dreamland.

Celebrated

Without doubt, however, the most celebrated attempt at cracking

the Italian iron man was made by a man who was reckoned to be able to punch

holes in just about anything: the mighty Bob Fitzsimmons. The experts on such

matters calculated that Ruby Robert’s scientific knowledge of punching would

prove the key to unlocking Mr Grim’s doughty little safe box.

Fitz was training for his light-heavyweight championship match

with George Gardiner and agreed to oblige Grim in the meantime. Perhaps Bob felt

that such an exercise would fine-tune the hammers that ballooned from the end of

his formidably muscled arms.

Robert Edgren, that grand boxing writer of bygone days, travelled

down to Philadelphia with Fitzsimmons and his party to watch the fight in

October, 1903. Edgren wrote: “Like all the others, I expected to see the Italian

iron man put away for at least a ten-count. It wasn’t possible to believe he

could stand up in front of Fitzsimmons, who had knocked out Corbett, Ruhlin,

Sharkey, Maher and scores of other great heavyweights. Fitzsimmons thought the

fight was a joke. But he wanted to catch a train home. He was in a hurry. He

intended to knock Joe out in a round.”

Fitz tried. How he tried. But he didn’t get his wish. Grim,

defiant as ever, made his intentions clear with a little speech before the

hammering began. “This Fitz thinks he’s gotta me scared. I tell you, he no gotta

this fellow scared. I Joe Grim. I no quit for no man in the world. I fighta da

Jeff next time, sure.”

Fitzsimmons didn’t quite know whether to feel amused or insulted

by the immovable object he encountered. After giving Joe a ferocious pounding in

the opening frame, Fitz strolled back to his corner and told ringside reporters,

“I hate to hit him – he’s so much fun.”

By the end of the third round, Bob’s expression had changed to

one of sheer bemusement. Grim’s face was a mask of blood from the repeated

smashes he had taken to nose and mouth. Each time he was hammered to the floor,

he simply laughed and stormed back into Fitzsimmons.

There were 17 knockdowns in all. Of the particularly brutal fifth

round, Robert Edgren wrote: “Fitzsimmons knocked Grim down three times with

blows that sounded like the impact of a mallet on a wedge.”

Not even Ruby Robert’s famous solar plexus punch could keep Joe

down. At the beginning of the sixth and final round, Fitzsimmons leaned across

and playfully tapped Grim on the head, as if trying to ascertain the apparently

unique structure of the Italian’s skull. Joe, of course, survived the session.

He even managed a celebratory somersault as he jogged back to his corner and

threw out his obligatory challenge to Jim Jeffries.

Secret

What was the secret to Joe Grim’s phenomenal resilience? Ace

trainer Harry Lenny believed he had part of the answer. Although Lenny had no

medical qualifications, he possessed a rare, physiotherapeutic gift for healing

aching muscles and bones. Lenny lived at the Forest Hotel in mid-town Manhattan

in his later years, offering free treatment to friends and charging fifty bucks

to strangers. During the war years, he was said to have secretly treated

President Roosevelt.

Lenny trained Grim for around five or six years and could never

quite believe the texture of Joe’s skin. “I never in my life felt skin like his.

It was smooth as a baby’s belly and it was as pliable as rubber. But the

strangest thing about Joe’s skin was the way it secreted a fine oil. I would

just touch his arm, shoulder or chest very lightly with my finger, and when I

took my finger away there would be a film of this fine oil where my finger had

been. I have always believed that Grim’s skin was a big part of his secret. It

was like a cocoon protecting him from danger.”

But even Joe’s skin and the exceptional quality of his cranium

couldn’t enable him to last out forever. The sad side of the Joe Grim story is

the great price he paid for the colossal punishment he took. Sailor Burke

finally knocked him out and Sam McVea duplicated the feat. Young Zeringer is

sometimes credited with knocking Grim out in three rounds at Pittsburgh in 1904,

but that result has always been disputed. It was Joe’s boast, don’t forget, that

he couldn’t be put down for the count. The Zeringer fight was stopped by a

compassionate referee who became horrified by Grim’s lust for punishment.

Whatever, the strange magic had finally seeped from the bottle

and Joe Grim was falling apart. We do not know how many fights he had, because

he never kept a record of his own incredible journey. He certainly won no more

than five or six. On July 28, 1913, he was admitted to a sanatorium, eventually

being discharged and apparently cured of his mental problems. He became a

shipyard foreman in New York around 1919, but was said to be mentally broken by

the time of his death twenty years later in a hospital at Byberry, Pennsylvania.

The heartening thing is that it is simply impossible to ever

forget Joe Grim. It always was. Before a fight with Al Kaufman, Joe was

described thus by writer TP Magilligan: “Of all the rich cards of the ring

pugilistic, this boy Grim has the lead by seven furlongs.”

Transformation

George Chuvalo had finally discovered the secret. No longer would

he be the likeable slugger who won some and lost some and took punishment like

no other heavyweight around. Now the Canadian Rock was punching correctly with

those meaty arms and had learned how to be a consistent winner. To cut through

the technical claptrap, old sage Charley Goldman had taught George to hold his

arms closer to his sides so that the weight of his body went with the punch.

It was late 1964 and George had just turned the heavyweight

rankings on their head with a dramatic eleventh round stoppage of Doug Jones at

Madison Square Garden. Joe Grim never scored a victory of such magnitude, but

then Chuvalo was a wholly better fighter than Joe and arguably just as

freakishly tough. Not once was George knocked off his feet in his 93

professional fights. He was also a terrific body puncher and undoubtedly a

knockout hitter.

What frustrated many worldly observers of the game was that a man

of such abundant raw talent was getting a reputation as a catcher when he had it

in him to be an ace pitcher. That raw talent never was truly harnessed and

polished. It teased and glimmered every once in a while and then got smothered.

Was George handled wrongly? Was he simply a bull-headed brawler who couldn’t

learn new tricks? We never truly know the answers to such irritating questions.

The Jones victory was indeed a lulu and Chuvalo looked mightily

impressive. There would be other big victories and false dawns that would enable

George to remain a stalwart of the heavyweight top ten for what seemed like a

lifetime. But always he was the slow plodder, the catcher, the guy who could

take a licking and keep on ticking.

The slick and smart boxers and jabbers like Muhammad Ali, Jimmy

Ellis and Ernie Terrell could never go wrong against Chuvalo. Yet take a look at

George’s stand against Ali at the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto in 1966, and you

will see the potential that went to waste. How I want to prod loveable old

George whenever I see that fight. How I want to urge him to punch more often,

bob and weave, duck and roll. Ali won the contest by the proverbial street, yet

the consistent surprise when we watch it afresh is its competitiveness. Fighting

as basically as he did, in more or less straight-up fashion, Chuvalo was able to

find Ali’s jaw repeatedly and smash him to the body and ribs all night long. A

sobering thought for those who maintain that Muhammad would have skated around

Rocky Marciano.

It’s in the bones!

After spending just under three rounds in the bludgeoning company

of George Foreman, Chuvalo compared the experience to being hit by a Cadillac

going at 50 miles per hour. Note, dear reader, that George did not say, “…being

run down by a Cadillac.”

Foreman’s Caddy knocked a fair few chunks out of the Canadian

Rock. But it couldn’t run it down or flatten it. Don’t ever watch the film of

that fight if something has gone down the wrong way and your stomach is feeling

a little tender. To this day, thirty-six years on, I cannot fathom how Chuvalo

managed to stay on his feet against the slow hail of crushing blows that soaked

into his head and body. George’s sponge-like resistance was quite something to

behold. Once Foreman’s punches struck home, they somehow seemed to disappear,

like a twister at sea that suddenly evaporates before it hits the land.

Chuvalo attributed his durability to his exceptionally solid and

absorbent bone structure. He would stand on his head for long periods to

strengthen the muscles in that famously thick and chunky neck.

On those rare occasions when his bones were broken, he couldn’t

be sure they were. He believes he suffered a busted nose at school after taking

a thump from a fellow pupil, only to be told by his boxing buddies to get into

the ring and forget about it. The theory was that a few more belts on the

schnozz would make the pain go away. The twisted nose became a trademark of

George’s rugged face, of which he was most proud.

Chuvalo could be no less conventional in the way he won bouts. In

a 1972 Canadian title fight with Charley Chase at the Pacific Coliseum in

Vancouver, George recorded a sixth round technical knockout. Chase certainly

took some punches, make no mistake about that. But it was a broken hand that

forced his retirement. Hitting George for any great length of time could be an

oddly harrowing and dispiriting experience. If it couldn’t break a man’s bones

or his very resolve, it could at least cause him to nod off at the wheel.

Bizarre

Jerry Quarry suffered such an experience in a bizarre fight that

quite probably represented the greatest and unlikeliest win of George Chuvalo’s

punishing and chequered career.

Jerry was very much the golden boy of the heavyweights in 1969, a

hugely talented and dangerous counter puncher, a marketing man’s dream with his

rugged good looks, a charismatic Jack Kennedy in boxing trunks. Quarry had

dismantled the previously undefeated Buster Mathis with almost technical

perfection, lost with great honour in a classic summer war with Joe Frazier and

was itching to get back into the fray against a fellow top ten contender who

could be presumed to be a reasonably safe opponent.

Chuvalo had reached the stage in his career where he fitted this

requirement perfectly. Promoters called on George at such times as surely as

movie producers call on Dennis Hopper to put some lumps on the leading man

without actually killing him.

Much like Joe Grim, however, George Chuvalo never once stepped

into a ring to lose. He saw his big chance against Quarry. And my, oh my, how

the Canadian slugger took it!

From the opening bell, the fight had a surreal air to it, as if

nothing at Madison Square Garden was quite in its proper order. George fell

behind on points, as he invariably did, but never overwhelmingly so. He was

always in the thick of the battle, rumbling forward like a little tank, scoring

with some punches and missing with others. He was competing with Quarry without

really giving Jerry the kind of challenge that concentrates a man’s thoughts and

keeps his brain ticking over.

Quarry needed that challenge throughout his career. He needed a

specific purpose to win, a sufficiently testing puzzle to solve. He thrived on

being written off and told he couldn’t win. He positively bristled at any

implication that his opponent could outbox or outpunch him.

Chuvalo, rock steady old George, wasn’t expected to do any of

these things. Where was the point to it all? When we are troubled by a pesky

wasp, we bat it away. We don’t find ten different ways to do it. Such was the

way that Quarry fought Chuvalo. Never underestimate the immense danger of a

tough old pro who just keeps hanging around, no matter what.

Jerry did a lot of damage with some classic textbook jabbing and

hooking, splitting George’s cheek open in the fourth round with a combination of

punches. Chuvalo was well accustomed to such treatment and continue to rumble

forward. It seemed that he simply couldn’t function properly without the impetus

of having his face turned into an abstract painting.

When the seventh round opened, George looked as if he had been

worked over by some bad people from Brooklyn. But he was still punching and

catching Quarry with some hefty clouts. Then Chuvalo hit the jackpot with a long

left to the temple that caused Jerry to stop and dither like a man who has lost

his keys. Quarry plopped down on his backside, clambered straight up and then

stumbled into a dreadful fog. He dropped back down on one knee to take a few

extra seconds as referee Zach Clayton tolled off the count. It was then that

Jerry discovered how hard it is to count from one to ten when your mind decides

to take an inconvenient vacation. He was still on one knee at ‘ten’. Out for the

count and out of the fight.

Hell came to breakfast in the Quarry dressing room as Jerry

thundered his protests. “Nobody knocks me out,” he insisted. “I was looking at

the clock and I couldn’t hear the count because the crowd was yelling so much. I

got gypped. I got ruined. That destroyed me. I could have gotten up. I couldn’t

tell the count by his (Clayton’s) fingers.”

Chuvalo’s response to Jerry’s tirade was as gorgeously blunt as

his fighting style. “If he couldn’t tell nine from ten, it must have been a good

punch.”

But what if George had been fighting Joe Grim that night? What

would have happened then? Why, of course, the two old pugs would have been going

at it forever. In a no-limit fight, it might just have been the longest draw

decision on record.

Hit me with your rhythm stick, hit me slowly, hit me quick.

Didn’t make any difference to those fellas.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|