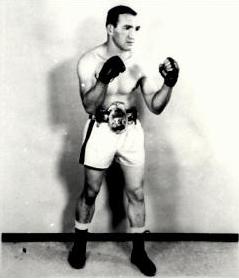

Cyclone From

The Beehive State: Irrepressible Gene Fullmer

By Mike Casey

In that charmingly twisted language that only fighters can make

sound sensible, Carmen Basilio once said of Gene Fullmer, “He did everything

wrong, but he did it right.”

Carmen knew what he meant and so did the rest of us. Even though

cold logic so often takes a battering in the crazy world of boxing, we tend to

stick with it as a measuring tool when confronted by those fighters who puzzle

us. We assimilate the facts and figures and try to reach a logical conclusion.

Heck, it worked OK for Mr Spock.

But prizefighters constitute a very special group of men. They

cannot be number crunched, packaged and neatly filed. They take pleasure, God

bless them, in turning the natural order upside down and twisting it inside out.

Nobody befuddled us more back in the fifties and sixties than

Gene Fullmer, the tough and bruising battler from West Jordan, Utah. It was as

if Gene had watched Rocky Marciano and set his mind on becoming even more

awkward, ungainly and downright contrary than Rocky.

In his early days as an unbeaten middleweight, Gene’s auditions

would make even the worldliest boxing people wince and reel in shock. They

didn’t come any worldlier than Teddy Brenner, who was the matchmaker at the

Eastern Parkway Arena in Brooklyn when he got his first look at Gene in 1954.

Brenner visibly sagged as he watched Fullmer lumbering through

his workout with a crudity and a lack of grace that would become all too

familiar in the years to follow. To those who witnessed the session, Teddy’s

horrified expression was something to behold.

Gene Fullmer was 24-0 as a pro at the time with an impressive 19

knockouts on his slate. How could he possibly look so bad? His most threatening

opponents seemed to be his own feet. Brenner, fearing that Gene might trip over

his plates and break his neck, implored Fullmer’s manager Marv Jenson to take

the kid back to the comparatively gentle environs of Utah for his own safety.

What had Teddy Brenner seen that had so dismayed him? He had seen

a man who couldn’t box or punch, whose awkward style would leave the average

boxing fan stone cold. He saw a fighter who, for all his impossible awkwardness,

could still be hit repeatedly with disturbing ease. Teddy kept watching and

blinking, looking for that certain something that he might be missing. He

couldn’t find it.

Brenner’s harsh verdict shocked Marv Jenson but didn’t deter him.

Marv had believed in his man Fullmer ever since the man was a raw and

enthusiastic young boy. At eight years of age, Gene was taken along to the West

Jordan Athletic Club by his father, Tuff, who asked Jenson to teach the lad

boxing.

Jenson saw at once what nobody else did. “He had it,” said Marv.

“I knew it the minute I tried him out. He had three things I could work on.

Strength, a good mind and fast reflexes. I took advantage of those three

things.”

Revelation

Gene Fullmer was a streaking revelation in his first years as a

pro, barrelling his way through the middleweight ranks with his peculiar brand

of bullish, cyclonic effectiveness. He was an exceptionally awkward revelation

to be sure, but nobody could beat him. He bulled, he charged, he hustled and

sometimes picked up as many lumps as he dished out. But he just kept winning.

The artists and the scientists of the ring must have gone back to their dressing

rooms wondering what had just rolled over them.

Starting out in 1951 with a one round knockout of Glen Peck at

Logan, Utah, Gene had taken his unbeaten run to 29 fights by 1954, fighting

mainly in his native Beehive State. He made his New York debut in November of

that year with a unanimous decision over Jackie LaBua and followed up with

decisive quality wins over Germany’s Peter Muller and future world champ, Paul

Pender.

Gene was moving rapidly into world class and his record over the

next couple of years is testament to the depth of genuine world class fighters

in the middleweight division of that era. It was near impossible to maintain an

unbeaten record in such a minefield of golden talent. When Gene lost three of

his next six fights, people wondered if the cream of the division had tumbled

the secret of the Fullmer style. The first harsh lesson came from Gil Turner at

the Eastern Parkway Arena in April 1955. Sporting a 47-7 record, Gil was a

highly capable ring mechanic who matched Gene all the way for toughness and

roughness. Turner knocked Fullmer through the ropes for a nine count in the

sixth round on the way to posting a convincing points win.

Gene learned from his mistakes and avenged the defeat just two

months later by out-hustling Turner in West Jordan. Fullmer seemed to be on a

roll again when he notched important wins over Del Flanagan and Al Andrews, but

then suffered successive back-to-back defeats for the first time in his career.

Both were unanimous decisions and both saw Gene hitting the deck.

The classy Bobby Boyd turned the trick at the Chicago Stadium in

a match refereed by former champ, Tony Zale, decking Fullmer in the third. Then

came the handsome Argentinian, Eduardo Lausse, a terrific puncher with a 63-6

slate, who downed Gene in the eight round of their Madison Square Garden

meeting.

Never usually one to complain, Gene was always niggled by the

Boyd knockdown, claiming that it was no more than a slip. Typically, Fullmer

ploughed on defiantly, beginning the five-fight run that would carry him to a

title shot against the great Sugar Ray Robinson.

There is a valuable lesson to be learned here for the excitable,

OTT boxing crowd of the present era. Educational, competitive defeats never did

harm a learning fighter and never will. How many times now do we hear of a

single loss being described as a ‘major reverse’ or a ‘disaster’? Small wonder

that the boxing fans of today, drunk on all the propaganda of the obsessive ‘0’

in a fighter’s loss column, should so hastily dismiss the great ringmen of

yesteryear. They must look at those 17 defeats on Dick Tiger’s record and wonder

what all the fuss was about.

How did Gene Fullmer and his contemporaries cope with adversity?

Well, for starters, they didn’t take a year off to ‘find themselves’. They

simply couldn’t afford to. They went back to the gym, eradicated the flaws in

their make-up as best they could and kept working to improve their technique and

their attitude of mind.

Fullmer’s losses to Boyd and Lausse were just two months apart

and both were tough and arduous affairs. Little more than a month after the

Lausse fight, Gene was back in the ring at the Cleveland Arena in Ohio against

no less a tough cookie than Rocky Castellani. Fullmer took a split decision off

Rocky and over the following eight months defeated Gil Turner for the second

time, Ralph ‘Tiger’ Jones, Charley Humez and Moses Ward. That’s taking care of

business!

Robinson

We harbour many misconceptions when we are young. As a wee lad in

the early sixties, I remember reading my father’s boxing magazines and thinking

how wonderful it must be to win a world championship. I saw those pictures of

Gene Fullmer from 1957 after he had taken the world title from Sugar Ray

Robinson at Madison Square Garden and remember thinking what a lucky man Gene

was. The fame! The glory! The money! Yes, Robbie was no longer the Robbie of his

peerless welterweight days. He was older, slower and getting caught out much

more often. But it still struck me as a colossal achievement on Fullmer’s part

to dethrone the legendary Sugar Man. In my youthful naivety, I wondered what

kind of mansion Gene lived in and how many millions he had stashed in the bank.

Well, Gene still lived in his same modest abode in Utah, where he

was still going to work as a welder. Such was the lot of the middleweight

champion of the world in those not so distant days. After a full day’s work, he

would train in the evenings, the victim of a boss who didn’t believe that a

fellow needed extra time off to prepare for Sugar Ray Robinson. One thinks of

Charley Burley finishing a long day shift and then making his way to the Legion

Stadium in Hollywood for the small business of taking care of Archie Moore.

Fullmer was very confident going into the Robinson fight. Gene

and Marv Jenson worked long and hard to secure the match, which only served to

fuel Gene’s motivation when he got the green light.

The unsung challenger prepared diligently for his greatest hour.

Gene recalls that he was very calm throughout his training camp. He didn’t agree

with the general consensus that Robinson was the greatest thing since popcorn.

This view was shared by Fullmer’s future opponent, Carmen Basilio, who insisted

that Willie Pep was the superior technician of the two ‘gods’ of that golden

age.

Gene would have four fights with the great Robinson before their

rivalry was concluded, but would not rate them among the toughest fights of his

career. Nevertheless, they were fascinating and significant chapters in the

history of the middleweight division, capturing the imagination of the boxing

public. They pitted the ageing artisan against the honest agriculturist, the

scales deliciously balanced by the slow ebbing of Robbie’s old magic and the

rise of Fullmer as a dogged and infernally difficult man to beat. Basilio was

correct in his later observation of the cyclone from West Jordan. Gene did

indeed do everything wrong, but few men could pick the confounding lock of his

almost unique safe.

The Fullmer camp hired tall sparring partners who were instructed

to fight in Robinson’s style. Gene learned to cut the ring off on them, pressure

them constantly and not allow them to get their shots off. He knew that Robbie

liked to punch from long range and that the way to negate the Sugar Man’s

wonderful skills was to shut him down. Fullmer practised over and over in the

gym, learning how to protect his chin from return fire as he bulled his way

inside.

The great plan worked like a charm on the night of January 2 1957

at Madison Square Garden. Robinson, gashed over the left eye and sent through

the ropes for a count in the seventh round, simply couldn’t cope with the

illogical, unorthodox bundle of energy that kept charging and washing over him.

Gene won the championship by a unanimous decision and the purists went home and

cried into their beer.

That left hook

Robinson had to get another chance. He always did. Even as his

thirty-sixth birthday approached and the last of his silky skills leaked away,

people could not believe it when he lost. Defeats were treated as aberrations

that had to be put right.

This time, however, those in the know believed that Ray was

finally tackling a bridge too far. Going into the return match at the Chicago

Stadium four months later, Robinson was a three-to-one underdog. It seemed

unbelievable. As somebody said, “Nobody was ever three-to-one over Ray

Robinson.”

Fullmer was convinced that he could take the old man again and

move on to even greater achievements. Robinson replied to that with six ominous

words that would become famous: “No man ever beat me twice.”

For four rounds, it seemed that the ‘experts’ had called it right

and Ray was deluding himself. Fullmer picked up from where he had left off in

the first fight, hustling and bullying Robinson out of his stride, attacking and

pressuring all the time. Everything appeared rosy in Gene’s garden. But one

shrewd fellow had his reservations. Trainer Marv Jenson was deeply concerned by

his man’s sudden recklessness. Jenson saw that Gene was too eager, too confident

and holding his hands too low as he came in. Even against the ageing Robinson,

these were dangerous invitations to disaster.

Jenson recalled, “When Gene was swinging hard, he was leaving his

chin open. I kept telling him to keep one hand up if he was going to swing like

that.”

Fullmer clubbed away to the body and was marginally ahead after

four rounds, but Ray remained patient as he sought to suck Gene into the

quicksand. In the fourth round, Robinson halted Gene’s forward march temporarily

with a combination of precisely placed punches. Fullmer took them well and

probably thought that he had soaked up the best that the old champion could

offer.

Robinson kept the faith. At his best, he could still read and

dictate a fight like no other man alive. The master tactician had seen the

encouraging signs and waited for the moment when he could drop the big bomb. The

bomb he dropped that night was one of the most precise and devastating left

hooks ever thrown in championship boxing.

It left Fullmer writhing in a state of semi-paralysis at 1:27

seconds of the fifth round, the first and only time in Gene’s career that he

heard the doleful decimal. Two whiplash rights to the body from Ray had shunted

Fullmer sideways, straight into the perfect firing line. End of game!

To his eternal credit, Fullmer was always admirably frank about

his one visit to dreamland. “It’s a sensation I’d never had before and one I

don’t necessarily want again.

“Robinson’s best punch was any punch he could hit you with. But I

felt without doubt that if I could beat him once, I could surely beat him again.

I felt that if I put more pressure on him, I could maybe knock him out.

“In the fifth, I moved in with my left hand maybe six inches

lower than it should have been, and he slipped that left hook over the top and

caught me right on the chin. All at once the lights went out. I had never been

knocked out. I had no idea what it felt like and I can’t tell you what it feels

like even now.”

Forget about it!

A disastrous defeat? A calamitous setback? Forget about it. That

was Gene Fullmer’s philosophy after the Robinson knockout. Gene went back to the

drawing board, worked at plugging the leaks in his game and entered the most

successful phase of his career. In the following years, the Cyclone would blow

and bull his way to victories over top drawer opposition in Ralph ‘Tiger’ Jones,

Chico Vejar, Neal Rivers, Milo Savage, Joe Miceli, Wilf Greaves, the

thunder-punching Florentino Fernandez and Benny ‘Kid’ Paret.

Gene would twice vanquish that most accomplished ring mechanic,

the dangerous Ellsworth ‘Spider’ Webb, as well as engaging in two memorable

brawls with Carmen Basilio.

There was also the matter of taking care of Mr Robinson once and

for all. By December 1960, when he met Gene for the third time, Ray was spitting

out his last defiant drops of genius, surrounded by a posse of snarling young

cats who wanted the great man’s illustrious name in their ‘win’ columns. It had

been 20 years and more than 150 fights since the Harlem Flash had begun his

astonishing professional journey.

Now he was walking the tightrope between his glorious past and

the barren future that he could not bring himself to acknowledge. But there was

one incredible effort left in Robinson when he faced Fullmer at the Sports Arena

in Los Angeles. By that time, Gene was the NBA champion and Ray had finally

found the man who could beat him twice. Boston firefighter Paul Pender had

relieved Robinson of the lineal championship earlier that year and then defeated

Ray in their return. Both fights were split decisions. Both showed the gaping

cracks now splitting Robinson’s once pristine armour. Surely Ray couldn’t turn

back the clock and come again.

He very nearly did. He failed heroically against Fullmer and only

by a whisker. The fight was declared a draw, producing a set of the most diverse

scorecards ever turned in by three wise men. Referee Tommy Hart had Robbie

running away with it by 11-4. Judge Lee Grossman saw it 9-5-1 for Gene, while

judge George Latka called it even.

It was Sugar Ray Robinson’s last great stand. When he took his

final run at Fullmer in March 1961, Gene bulldozed his way to a unanimous points

win at the Convention Center in Las Vegas. The well had run dry for Robbie. So

began the final, poignant chapter of his career when he would travel the world

chasing ghosts.

Brawling with Basilio

Perhaps the three fights that defined Gene Fullmer during his

bruising, stormy reign as NBA champion were his two wars with Carmen Basilio and

his ferocious, foul-filled struggle with Joey Giardello.

The Giardello fight, at the Montana State College Fieldhouse in

Bozeman in April 1960, continues to reverberate comically to all but the two

participants. Both men were guilty of tearing up the rulebook, yet both

continued to protest their innocence as the years rolled on.

Gene, as proficient a billy goat as there ever was, claimed that

Joey blatantly butted him. Joey, who knew every trick in the book, insisted he

only did so because Gene had butted him first.

Fullmer suffered a bad cut to the head, claiming that Giardello

rammed him after locking his arm. But none of that was important anyway, said

Joey, because he beat Fullmer out of sight and the decision stank. Giardello

believed he won nine or ten of the fifteen rounds and wanted to fight on at the

finish.

At ringside, the Fullmer and Giardello brothers were threatening

to fight each other as a sideshow attraction. It was some night in Bozeman and

every man in the house was a good guy who had been wronged.

Fullmer’s slugfests with Basilio for Gene’s NBA championship were

marathon tests of endurance between two of the great tough guys of the ring.

Carmen was on the wane after a hard career fighting the best welterweights and

middleweights in the world, but the gutsy New York onion farmer from upstate

Canastota simply didn’t know how to go quietly.

He was locking horns with something of a soul brother in Fullmer,

but Gene was bigger, younger and stronger.

Fullmer stopped Basilio in the fourteenth round of their first

brutal contest at the Cow Palace in San Francisco in 1959, but it was in the

battle of Derk Field in Salt Lake City in the high summer of 1960 that the

fireworks went off in earnest – in more ways than one.

Gene produced his most commanding performance in a gruelling

battle of physical strength and high emotion. Carmen, an immensely proud man who

had traded on his fighting heart and toughness for so long, seemed to fall apart

all at once as old Father time caught him by the tail and sent him asunder.

Bulled and battered, slugged and mauled, Basilio was rescued by

referee Pete Giacoma in the twelfth round. The act of compassion was not

appreciated. His eyes cut and his body covered in ugly welts, Carmen raged at

Giacoma and had to be escorted back to his corner by police officers.

“Gene and I are good friends but this Utah Athletic Commission

belongs to Marv Jenson,” Basilio stormed in the aftermath. “And that referee –

he never should have stopped it. He could see the handwriting on the wall.”

Like every proud warrior in denial, Carmen had seen a different

fight to the one that had taken place. The Reno Evening Gazette reported: “The

battered ex-champion was obviously hurt by Fullmer lefts to the body and right

shots to the face. Bleeding, reeling and holding on in the twelfth, it appeared

the end was near one way or the other.

“There were no knockdowns, but in the eighth Fullmer crashed into

Basilio as he was going away and Carmen went flat on his back, came up on his

shoulder, then back on his feet again like a seasoned tumbler.”

Basilio had found out what it was like to fight Gene Fullmer.

Like so many others who had engaged the curiously likeable slugger from Utah,

Carmen staggered from the fray disbelieving his cuts and bruises and his aches

and pains. How could such a crude and apparently rudderless barge of a man

inflict such damage?

Perhaps even Gene Fullmer himself never quite knew the answer to

that one. But six months into a new decade, the cyclone from West Jordan was the

monarch of all he surveyed. He was doing it all wrong, but he was doing it

gloriously right.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|