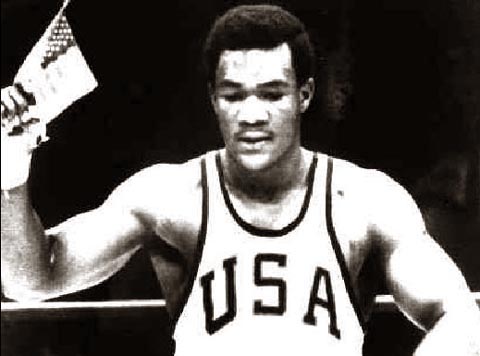

Almost The

Man: But Big George Is Not A Top Five Heavyweight

By Mike Casey

Never assume that the title of ‘boxing historian’ makes a guy

feel grand or superior. Only the insufferably smug and deluded feel like that.

Trust me when I tell you that the one thing most of us dread is that bold new

message in the inbox that opens with the quietly chilling words, “Hey, you’ll

know the answer to this one….”

When a fellow historian is lurking on the other end of it, the

heart beats even faster, the guard goes up and the ridiculous feinting begins. I

had one such message just the other day from a friend and fellow obsessive who

mischievously asked: “How hard did George Foreman hit? And how does he stack up

on the all-time heavyweight list?”

Yikes! Two questions! The shifty rascal! Sheer instinct

enabled me to take care of the first one. “Damn hard, sir, if we’re being

frank.”

It brought me a few precious seconds while I retreated to the

ropes, lolled about for a while and had a think about the second query.

Just how great really was George Foreman? The question intrigued

me, because Big George is arguably one of the most difficult of the great

heavyweights to assess and assign his rightful place. For let us be sure of one

thing, he was indeed a great heavyweight. He might just have had it in him to be

the greatest we ever had.

In the years to come, I confidently predict that Foreman’s

all-time star will rise as he becomes the new darling of the ‘cool’

revisionists. He is the ideal candidate, because he was so nearly the great

invincible before he tripped and stumbled in the blackness of a distant jungle.

I have Foreman seventh on my own all-time list, just a notch

below Jim Jeffries, and I look at the names of those two titans constantly and

sometimes wonder if I should have them higher. For all-time rankings are no

different from current rankings in the way they fidget and shift and change

shape. They just evolve more slowly. Our knowledge of old and new fighters

increases as time goes on, and our gut instinct begins to relay new messages

that sometimes conflict with the old. Any so-called historian will very quickly

lose credibility if he is too blind or too stubborn to recognise a necessary

changing of the guard.

It is fitting that Foreman and Jeffries should give me a

headache, since they shared so many similarities. Both were among the strongest

men who ever stepped into the prize ring, and I am talking here of natural

strength. This is a concept that is so often misunderstood by many, much in the

same way as natural punching power.

The legendary tales of Jeff’s strength are quite true. He was an

immensely powerful man, and Big George was similarly blessed. Their weights were

near identical in their prime years, around 220lbs, and that was natural weight

and natural muscle. These were men who didn’t need to beef up on excessive

weight training, nutritional and protein supplements or performance-enhancing

drugs with suitably vague and marketable names.

I would confidently wager my money on Jeff or George beating a

360lb Wladimir Klitscko every time in a flat out push-and-shove contest.

However, one important factor separates Jeffries from Foreman in

the all-time reckoning. Jeff, in his prime, was never beaten. George was. He

shouldn’t have been, but he was. When I interviewed him a few years ago and we

finally got around to the Ali fight in Zaire, George gave a wry grin and said

quietly, “Yeah, him of all people. Man, I couldn’t get that one out of my head.

I still can’t.”

The trouble is, nor can anyone else.

Exception

The enormous frustration of the Ali disaster is that George

Foreman so nearly reached the finishing line as a remarkable exception to a

couple of general rules. He won the richest prize in sport with a limited

repertoire of fighting skills. He won it by bulldozing thirty-seven mainly

nondescript opponents and then similarly crushing a genuinely great champion in

Joe Frazier in the acid test that was supposed to find him out and knock him

back down the ladder.

Muhammad Ali memorably christened Foreman ‘The Mummy’, an unfair

and somewhat cruel summation of George’s fighting abilities. Foreman, for those

who actually took the trouble to study him, was always more than a simple

stalker and banger. He was no Jack Dempsey for speed, variety of attack,

movement and general ring science. He was no Jack Johnson or Ali for cleverness,

guile and psychology. Nor could George match Joe Louis for pinpoint precision

punching. Louis possessed a far superior punching technique, as well as a

wonderful jab that was an immensely damaging weapon in its own right.

Yet we come back to that word ‘exceptional’ in Foreman’s case,

for he was indeed an exception at the brutal basics. George’s trainer, cagey old

Dick Sadler, taught his man how to utilise God’s natural gifts and be the boss

of every situation. George was a shuddering puncher and an instinctive ring

hunter who intimidated most of his opponents and cut off their escape routes

with often deceptive skill. He pushed, he shoved and he employed a very damaging

jab when he saw fit.

His emphatic crushing of Frazier and his annihilation of Ken

Norton offered comprehensive proof that Foreman was no less devastating at the

highest level. So many other fighters, built on the weak stilts of inferior

opposition, have been savagely exposed when stepping up to the major league.

Fresno hitter Mac Foster, the great rage of the late sixties and a contemporary

of the young Foreman, knocked out twenty-four men in a row before being brutally

punched back into line by Jerry Quarry.

Foreman took that particular script and simply ripped it up. By

his own admission, he never did stop kicking tomato cans to keep busy and pad

his record. He got it away with it to the very end, through what was effectively

two careers, because he simply wasn’t like any other heavyweight of a similar

portfolio.

As an older man, during his second coming, Foreman learned

patience, economy and better punch timing, because his age and increasing

slowness demanded a more measured and intelligent approach. His formidable

punching power never decreased and was probably never more graphic than in his

sudden destruction of Michael Moorer with a single blow that resembled little

more than a casual tap.

Special

George Foreman’s standing as a special and almost unique talent

was evident from very early in his career, as was his ability to shock opponents

into defeat and leave them in a suspended state of disbelief for some time

afterwards. While his style and attack were not as cultured as that of his

kindred spirit, Sonny Liston, George was no less proficient at mentally

shredding the other man’s awareness and causing him to freeze in his tracks.

Those opponents who saw any light at the end of the tunnel were usually staring

at Foreman’s oncoming train.

In 1970, at Madison Square Garden, Foreman stopped Boone Kirkman

in two brutal rounds, weighing 216lbs to Boone’s 203. Kirkman was the last great

heavyweight hope of manager Jack ‘Deacon’ Hurley, who had suffered previous

disappointments with Harry Matthews and Charlie Retzlaff. Soon after the opening

bell, George placed his gloves on Boone’s shoulders and shoved him straight on

his backside. The fight effectively ended right there and then. Psychologically

shattered, Kirkman stumbled and spun around as he was struck by a hail of heavy

jabs and power shots. He was on the canvas four times before referee Arthur

Mercante rescued him.

In the dressing room, Kirkman still couldn’t fathom how the roof

fell in. “I don’t believe it,” Boone said. “I just can’t believe this happened

to me.”

Three months before, Foreman had manhandled George Chuvalo, that

toughest of tough guys, in similar fashion. Look at a replay of that fight and

it is hard to believe that the weight differential between the two men was just

four pounds in Foreman’s favour. Chuvalo stayed on his feet (he always did) yet

looked like a man being flung around in the jaws of a playful lion.

Joe Frazier was similarly bullied and battered in Kingston, often

looking small and almost insignificant as he was bounced repeatedly off the

canvas, yet Joe was spotting George just three pounds that night.

Now, if you will, get a willing friend of similar weight and try

to shove him back just a few inches. It is an enormously difficult thing to do

if he is prepared for it. If he is naturally strong, he will then send you

reeling with a push of comparative mildness.

We get the point, then, about natural strength. But what about

natural punching power? How good was Big George Foreman in that department?

My good friend and fellow historian Mike Hunnicut studies hours

of quality film in his painstaking analyses of the great fighters. Every

conceivable aspect of their game is put under Mike’s microscope with an

objective eye. Of Foreman, Mike says, “He had great natural power and great

strength, using it to grab, pull, turn and push his opponents off balance. In

the first four rounds, he would use all of his power to knock out men or damage

them to an eventual defeat. For sheer impact, he was the hardest hitter with two

hands since Sonny Liston.

“On the minus side, George never had great balance or

co-ordination. He also threw himself further off balance by over-extending his

punches. He leaned over too far when he was doing this, pushing his punches

because his balance was too far over his front leg. Foreman never had short

power, which requires fast turns and shifts. Consequently, he would often fall

into his opponents, shove them and regroup.

“Of the ten ex-fighters and trainers I know who saw Foreman,

Dempsey and Louis, none of them picked Foreman as the hardest puncher. Foreman

could hit, no doubt about it, but on the best days he ever saw he never reached

the level of Dempsey, Louis or Max Baer.

“Dempsey – a one of a kind hitter – and Louis come out as the

elite punchers again and again. If you measure the average range from which the

great heavyweights could generate knockout power, Jack is first at between

one-and-a-half and two-and-a-half feet and Joe is his only challenger at between

two and three feet. The rest are also-rans. To break the two-feet barrier,

you’ve really got to be something.

“People talk misty-eyed about six and nine inch knockout shots,

but that’s a big exaggeration if you are measuring the punch in the correct way.

The shortest knockout blow I have seen was the eighteen inch shot with which

Dempsey knocked out Firpo. That’s going some – that’s as good as it gets.”

Pure

Mike Hunnicut makes some very correct and important observations

here, which are often overlooked in all the excitement that accompanies a

genuine giant of the ring when he is on the rampage. The bigger the man, the

more awesome the destruction can seem. Yet for all his vaunted power, the prime

Foreman was essentially a clubbing puncher who rarely put opponents into a

slumber with a single shot, save for the lesser opposition he simply scared into

taking the ten count.

Big George’s ring kills were invariably drawn out, as he was

forced to knock down opponents repeatedly to finish them off. Dempsey, Louis and

Marciano had many such nights, but those three killers of the ring could also

end a fight suddenly and devastatingly with one, two or three-shot blasts. They

quite literally put their opponents to sleep, which is why I have to place that

stellar trio at the top of the hitting tree. Dempsey felt that Marciano was

arguably the best of them all in that regard. “One smash and it’s all over,” was

Jack’s summation of Rocky’s punching power at its very sharpest.

For all that, Foreman remains a deliciously square peg that

simply will not fit into any round hole. There is one simple reason for this and

it comes in the form of a mind-bending little question: Would you confidently

bet everything you own on Big George losing to any heavyweight in history in a

one-off head to head battle? I suspect not. That is how potentially dangerous

the prime Foreman was. Alas, ‘potentially’ is the key word in assessing George’s

place in history.

The big defeat to Ali has been dissected and discussed countless

times since that incredible night in the sweltering heat of Kinshasa in 1974.

Did Ali win it? Did Foreman lose it? Yes on both counts. I confess here and now

to having never been a great Ali rooter, since I feel that he brought as many

bad things to the game as good. He clutched like a thief from the very start of

his career, mostly with impunity as a generation of otherwise competent referees

became as awe-struck by his charisma as the blind faithful who would never hear

a word uttered against him. It was also Ali who led us down the current garden

path of tasteless insults and boorish behaviour. He tortured some opponents in

the ring quite beyond reason and took pleasure from doing so. His kindergarten,

rinky-dink poems were lauded by the usual fawning ‘intellectuals’ as the

literary stuff of genius.

As a simple fighting man, however, he was an astonishing athlete:

multi-talented, teak-tough and with the heart of a lion in the trenches. He

wilfully refused to be beaten, even as he stared down the barrel and heard the

click of the trigger.

We will never know for sure if Muhammad’s game plan in Zaire was

a tactical masterstroke from the outset or half a plan that required some hasty

improvisation and a dash of luck. But he did it. He pulled off one of the

greatest victories ever seen against a George Foreman whom many genuinely

believed might literally kill him.

As to the theory that George fought the right kind of fight but

simply ran into the only man who could withstand his artillery, I disagree.

Given the heat and the opponent, Foreman fought with terrible recklessness and

lack of thought. Even in the early rounds, when he was still fresh, he was

swinging round the houses and expending terrific energy unnecessarily. He was

firing crushing punches for sure, which should have done for any other opponent.

But Ali wasn’t any other opponent and George knew that. Foreman flailed like an

amateur in his increasing state of panic and exhaustion, when a couple of calm

and disciplined shots - even as he neared the moment of death - might still have

saved his bacon. He erred both tactically and mentally, and the last small fires

from that wreckage continued to simmer and sting him for the remainder of his

career.

Effects

The effects of that monumental defeat continued to be apparent

through Big George’s fights with Ron Lyle and Jimmy Young, in which Foreman

never seemed sure of himself. He lost faith in his ability to stay the distance

and became too obsessed with the popular notion of the time that he was badly

lacking in stamina. I do not believe he was, not radically so. But he was

lacking in mental strength and self-belief. His nose had been bloodied by the

one cocky kid in the class who didn’t fear him. To any man who trades on fear,

that is the worst kind of hiding to take.

Foreman, for my money, did a pretty remarkable job in his second

coming. Refreshed and with a more relaxed attitude to boxing and life in

general, he fared admirably well for an old fellow in calmer heavyweight waters

that had been deserted by the big sharks of his golden era.

Add up all the parts of a curiously fractured and often fabulous

career, and what do we have? We have a great heavyweight who, at his very best,

would have scythed his way through the majority of his predecessors. It all

depends how you rank them. I still maintain that the fairest possible way to all

parties concerned is to weigh all the relevant physical and mental strengths and

combine them with overall career achievement. But you have to work damn hard at

it, study hours of film and research and not play favourites.

The who-would-beat-who system is always good fun and preferred by

many, but leads to many gridlocks. One is the dreaded triangle where A could

beat B, B could beat C, but C could beat A. Actual series between the greats can

be just as entangling. Ezzard Charles was three for three over Archie Moore, but

was Ezz really the superior light-heavyweight over the long haul? Was Fighting

Harada truly a better bantamweight than Eder Jofre? Was Sandy Saddler on the

same plane as Willie Pep among the featherweight masters?

In the fantasy world of an all-time heavyweight knockout

tournament, George Foreman would be the bristling dark horse that every other

contender would wish to avoid. On power punching ability alone, I would place

Foreman in the second tier with the likes of Liston, Tyson and Baer, but firmly

behind the supreme talents of Dempsey, Louis and Marciano. Give George fourth

position in the power stakes and you will get no great argument from this

corner.

Foreman, however, is not a top five heavyweight when all of the

other essential categories for qualification are properly and thoroughly

examined. What he had, he had in frightening abundance. But he didn’t have

enough to make it to the premier division. And oh, that one mad and surreal

night in Zaire! We simply cannot let that one go and nor can George. He will

tell you as much in his quiet moments.

Harshly, in my view, he does not rate himself among the all-time

top ten. That is an honest judgement on his part and not a reflection of his

famously self-effacing humour.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|