Not Fade Away:

Genius Of Bob Fitzsimmons Must Shine On

By Mike Casey

Sometimes I go to bed at night worrying that great old fighters

will be forgotten. I know that’s stupid in a world of vastly more immense

issues, but I can’t help it. I worry that the brave and skilful ring wizards of

yesteryear will finally be enveloped and swallowed up by the mists of time as we

finally overdose on the great rush of getting to the next big thing. Even what’s

happening right now is no longer a sufficiently potent drug to keep us high.

I despair each Sunday evening here in England when my enjoyment

of my beloved NFL football, which CBS thoughtfully slips in between the

commercials, is shattered by the dreaded words, “Coming up….”

The ball from the opening kick-off is still pleasantly enjoying

its hang time when a booming voice starts telling me what’s coming up next

Sunday. You think this game is going to be great? Next Sunday’s game will be

even greater! And, hey, we’re only eight weeks away from the Super Bowl!

Any rare trips down memory lane are coated in the familiar,

patronising paint. The likes of Joe Montana, Walter Payton and Johnny Unitas are

faded into sepia to the accompaniment of a haunting piano, just to remind us

that they were pushing pigskin in the ice age when they were damn lucky not to

run into a guy like Terrell Owens.

Old boxers take an even bigger drubbing. I cringe whenever Jack

Johnson and Stanley Ketchel are wheeled out of the archives like a couple of

dancing bears, tearing hither and yon on that familiar old herky-jerky film.

What a pair of characters! Old Jack was a one, with that permanent grin and the

way he twirled his fists in that funny little motion. And old Stanley was a bit

of a case too, a mad punching bag who kept getting his teeth knocked out. Cue

rinky-dink tune and watch the fools tripping over each other!

I have to pull myself together at such times. I have to remind

myself that the home fires will be kept burning for the wonderful fighters of

old by the usual good men who know a genuine nugget from fool’s gold and take

the time and trouble to mine the distant hills.

They dig for the truth, piece together fractured records with

undying patience and tenderly doctor crumbling fight films with technological

wizardry that is far beyond the grasp of this humble hack. Long may their

sterling work continue, for they face a formidable army.

When I sat down to present the considerably weighty case of Bob

Fitzsimmons as one of the elite geniuses of boxing, I anticipated the nature of

the first ambush. “Bob Fitzsimmons? How do you KNOW? Where’s the proof? There’s

no DVD of him!”

Despite the fact that old Bob was on the prowl more than a

hundred years ago, it never ceases to amaze the new-age dilettantes that his

greatest hits cannot be found as readily as those of Bob Dylan.

Well, folks, nor do we have real time DVDs of the American Civil

War, the English War of The Roses or the Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. But

at some point, surely, we have to trust the thousands of testimonials of those

who were there. Whatever the political slants of the reams of letters and

eyewitness accounts, we know for a fact that these monumental events took place

and that they were driven and shaped by fighting men of astonishing courage and

vision.

Now I challenge you to find and assimilate the evidence for Bob

Fitzsimmons, if you can be truly bothered to do some serious digging. You will

find a recurring theme that goes far beyond mere praise and even awe. That theme

is one of disbelief at what Fitzsimmons could do as a scientific boxer and

puncher. Here was a middleweight who retained his standing as the third greatest

heavyweight of all time in the eyes of Nat Fleischer until the day of

Fleischer’s death in 1972. Fitzsimmons weighed barely 150lbs when he won the

world middleweight title from Nonpareil Jack Dempsey. Bob was still only 167lbs

when he took the heavyweight championship from Jim Corbett.

Fleischer saw most of the great champions in his lifetime,

including Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali. Was Nat really just an old guy living in

the past? I suspected so for many years. Now I seriously wonder. He was one of

the first to recognise and publicise the blinding talent of Ray Robinson. Nat

couldn’t praise Eder Jofre sufficiently and was a consistent champion of Dick

Tiger. Back in 1966, when it was still the vogue to pick holes in Muhammad Ali’s

technique, Fleischer hailed Muhammad as ‘a thoroughbred champion’.

Nat’s contemporary, Broadway Charley Rose, who had a great eye

for talent, was similarly generous in his praise of Ali. Yet Rose never wavered

in his estimation that Fitzsimmons, Jim Jeffries and Sam Langford were three of

the greatest fighters ever to draw breath.

The mighty Jeffries, who dethroned Fitzsimmons, could never get

over Bob’s talent as a man apart. One tries to play the Devil’s Advocate and

shoot a hole through all the glowing reports and lavish praise. But in the case

of Fitz, the positives just keep piling up.

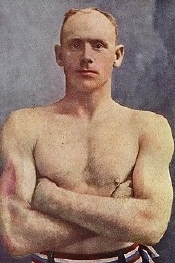

Forget the bald head, the freckled face and the vacant grin that

was his peculiar, facial trademark. Forget the spindly legs that cartoonists

loved to mock. The genius of Fitzsimmons came from a highly scientific and

analytical mind that was able to perfectly relay messages to the muscled arms,

the broad shoulders and the powerhouse of a back that were hewn from long and

hard days as a blacksmith.

Some

puncher

They could call it the solar plexus punch or anything else they

wanted. Jim Jeffries knew differently. Jim knew because Bob Fitzsimmons, the man

himself, had told him. “Fitzsimmons was the greatest short punch hitter I ever

saw,” said Jeff. “He could sure snap them in with a jar. You remember how

everyone thought he knocked Corbett out with a solar plexus punch? Well, old

Fitz told me years afterwards that he didn’t hit Corbett in the pit of the

stomach at all.

“He got Corbett to leave an opening, shifted and just stiffened

his left arm out and caught Corbett on the edge of the ribs on the right side of

the solar plexus, to drive the ribs in with the punch. I used the same punch on

Corbett myself in San Francisco, and you remember how he went down. That was

Bob’s greatest punch and nobody else ever learned to use it the way he did.”

That famous punch from Fitz had a tragic effect on Corbett’s

father. Crushed by his son’s failure, the old man took up his gun and shot

himself through the head.

When Jeffries was training at Asbury Park for his first fight

with Jim Corbett, Fitzsimmons was slowly on the wane and about to do battle with

the hulking 300lb Ed Dunkhorst, who carried the nickname of ‘The Human Freight

Car’. There was no doubt in Jeff’s mind that Fitz would prevail.

The great former champion Tommy Ryan, confidant and trainer to

Jeffries, wasn’t so sure. Recalling how Jeffries had punched Dunkhorst in the

body while using him as a sparring partner, Ryan said, “Ed’s too tough to be

knocked out in a hurry.”

“Oh, that old guy’ll get him,” Jeff insisted.

Fitzsimmons did indeed get Dunkhorst. Bob sank a left hook deep

into the giant’s stomach and knocked him out in the second round. It was more

than The Freight Car could bear and he wandered off to the gentler occupation of

selling tickets in a theatre.

We simply do not know how many fights Bob Fitzsimmons had or how

many men in actual total fell victim to his paralysing power. But we can fashion

an approximate idea. My fellow historian Tracy Callis is a known demon for

getting to the guts of these things. The deeper Tracy digs, the more he becomes

impressed by the depth of Fitz’s ledger and the special talent with which it was

compiled.

“By personally searching through old newspapers and microfilm, I

have compiled Fitz’s record at 85 wins, eight losses and two draws, with 125

exhibitions and 32 no decisions (many of the old reports were vague and so these

bouts were counted as such). Of these 157 bouts, many were likely to have been

‘for real’ contests that would have translated into more wins for Fitz.

“Bob fought light-heavyweights and heavyweights for more than

half his career. Had he fought his entire career as a middleweight, what would

his record have been?

“Suppose those exhibitions and no decision bouts were wins? Not a

ridiculous stretch, they likely could have been. Then Fitz’s record would have

been 242-8-2. Still speculating, let us project eleven of these as losses to

give Bob a total of 19 defeats like Ray Robinson. Even then, Fitz would have

been 231-19-2.

“Fitzsimmons claimed to have had more than 350 bouts and maybe he

did. Had he fought only middleweights, he would have won, what, 340 of these?

What would his record have looked like then?

“Fitz had eight ‘official’ losses, but look at who beat him: Jim

Jeffries (twice), Jack Johnson, Philadelphia Jack O’Brien and Bill Lang, all

late in Bob’s career. He lost to Mick Dooley and Jim Hall very early in his

career, while the disqualification loss in Bob’s first fight with Tom Sharkey

was due to a foul called by the referee and Tom’s good friend – Wyatt Earp!”

Drawing breath

Noted boxing writer Robert Edgren was still drawing breath after

watching the great Mickey Walker batter Ace Hudkins in late 1929. Walker was

something else and Edgren was generous when comparing Mickey to the great

middleweight champions who had preceded him.

Wrote Edgren: “Others have contrasted Mickey with Fitzsimmons,

Ketchel, Papke, Greb, Tommy Ryan, etc, etc., usually with the comment that any

of these gentlemen could have knocked Mickey for a goal in a round or two. I

don’t figure Mickey so low in the championship scale.

I’d say that he could have given Ketchel, Papke, Ryan or any of

the lot a whale of a fight, with a fairly even chance of winning. But we’ll

leave Fitzsimmons out.”

The reason for Bob’s omission? Mr Edgren explained: “It is cruel

to compare other middleweights with Fitzsimmons, because no other middleweight

that ever lived could have had a possible chance against Bob.

“Fitz was a man with a peculiar fighting build. He was about six

feet tall, had very wide shoulders and long arms, and a light body and small

waist and thin legs. His weight was all hitting weight. He was the hardest

hitter in the world – even among the heavyweights when he was still a

middleweight. He had the quickest, coolest and most resourceful mind in his

profession. There was only one Fitzsimmons and I don’t expect ever to see

another.”

Big Gus Ruhlin would have had little argument with that

assertion. Knocked out in six rounds by Bob at Madison Square Garden in 1900,

Ruhlin vowed he would never fight ‘that Fitzsimmons’ again. Fitz had struck Gus

with such a hammer blow under the heart that the simple act of breathing became

agonising for Ruhlin over the following two weeks; by which time Fitz was

lowering the boom on Sailor Tom Sharkey in the second round at Coney Island.

Fitz really struck a purple patch in that golden autumn of his

long career, seemingly hitting harder than ever as he moved menacingly towards a

return match with Jim Jeffries. Once again, Bob came up short against the iron

man of the ring, but gloriously so.

He had punished Jeffries terribly in their first memorable

encounter, before Jeff had come thundering through to score that unforgettable

eleventh round knockout. The return match was similarly torrid for Jeff before

the ageing Fitzsimmons finally crumbled from the Boilermaker’s crushing blows.

Jeffries was virtually blind from the blood of his facial wounds

when he brought down the curtain in the eighth round. Fitz, outweighed by

47lbs, had opened gashes over Jeff’s eyes, broken his nose and cut both of his

cheeks to the bone.

Promoter Jim Coffroth was awe-struck by Fitz’s talent. “I don’t

think there ever was a man in the ring under 200lbs who could hit as hard as

Fitzsimmons.

“As a general rule, we find the clever fellow lacking the punch

or the good puncher lacking the cleverness. Take the fighter who has the punch

and the ability to deliver it properly, with a physique that permits him to

stand one in return, and he is usually invincible against your so-called clever

men.

“Now, Fitzsimmons had all these great qualities, was the hardest

hitter I ever saw, was game and clever when he wished to be and was exceedingly

crafty.

“Also, Fitzsimmons had that quality known as bottom, which is a

most valuable asset in a fighting man.”

Greatness

Boxers instinctively know when they are sharing the company of

greatness. As the legend of Bob Fitzsimmons grew, so the champions of the future

were drawn to him like magnets. Even the Old Master learned from the original

maestro. Joe Gans, that multi-talented colossus of the lightweights, claimed

that he learned virtually all of his boxing skills from Fitzsimmons. The young

Joe ditched his job in the Baltimore fish market when he got word that Fitz was

staging a road show and taking on anyone who would fight him. Night after night,

the eager and fascinated Gans studied Bob’s moves.

Finally, Joe plucked up the courage to approach Fitz and engage

him in conversation. Bob liked what he saw and heard. He recognised at once that

Gans was a willing and intelligent student and imparted much invaluable advice

to the youngster in their time together.

What Joe saw fascinated him. He believed Fitz to be the master

strategist of the ring, in a league of his own. He was cunning, versatile and

thought out every punch and manoeuvre. And still he was holding back and not

showing all his cards. Gans, for all the brilliance he saw in Bob, was convinced

that the Cornish wonder was keeping his aces craftily tucked up his sleeve.

The great Kid McCoy, who would wreak havoc among the

middleweights and light-heavyweights, was no less entranced by the workings of

the Fitzsimmons mind. So eager was the Kid to learn from Fitz that he took a job

as the great man’s dishwasher before progressing to the prized role of sparring

partner.

McCoy had a devilish and deceitful mind of his own and was

determined to equal and surpass Bob as the fox of the roped square by playing

him at his own game. McCoy would learn new tricks from every session whilst

holding plenty of his moves in reserve. It seemed like a great plan. Fitz knew

that he was duelling with a like-minded soul and upped his work rate

accordingly, showing the Kid more and more. But McCoy, like Gans, could never

ferret out all of big Bob’s jewels.

“Whenever I thought I had learned everything, Fitz knew it. The

old fox would slip something brand new over on me. He always had something up

his sleeve that I never thought of. That is why I never fought him afterward. I

never could get to the bottom of his mind the way I could with all the others.

“Fitzsimmons was an adept at protecting himself. Let fly a swing

at him and 99 times out of 100 your glove landed on one of those freckled

shoulders of his.

“There was a great man. I consider Fitz the best fighter I ever

knew. Jack Johnson? Not on your life. Fitz (in his prime) could have licked him

with ease.”

McCoy learned other tricks from Fitzsimmons. Bob would devote

much time to studying the graceful movements and reflexes of predatory animals

such as bears and the big cats; just as Charles Atlas, in later years, would

study how lions and tigers stretched and exercised, incorporating their

instinctive know-how into his callisthenic exercises.

What else do big cats know? They know how to conserve their

energy. So did Fitz. It was his habit to remain on his stool for a couple of

seconds after the going to start a round, often rising only when his opponent

was halfway across the ring. Even then, Bob didn’t rise in the traditional way.

His seconds would grasp him under the arms and lift him to his feet. In his

pomp, Bob also perfected the art of being back at home base by the round’s

conclusion. His cornermen would signal when there was ten seconds remaining and

Fitz would cleverly manoeuvre himself and his opponent across the ring to the

appropriate location.

Although Fitzsimmons trained hard, he never over-reached himself.

His sparring sessions were intelligently executed and often spare in their

nature, following a similar pattern. It was his preference to have his sparring

partners attack him, so that he could practise his slipping, blocking and

counter-punching. One can only imagine the discomfort of Bob’s employees

whenever he uncorked a meaningful shot to the body.

The Kaplan and The Kid

Boxing buddies Hank Kaplan and Curt Narimatsu, who know a fair

old bit between them, are frequently like apples and oranges when comparing

fighters of different eras.

Says Curt: “Hank’s astute mind typifies progressive evolution,

that today is better than before and tomorrow will be better than today. I’m

from the school of ancestor worship/tombstone idolatry, because to me the

greatest fighters adapt to the times.

“Fitz didn’t have Ali’s movement, but Bob was mobile. A twitch of

the cheek, a shoulder feint or a leg shift were enough to distract the foe.

Remember how basketball’s Bill Russell stepped on Wilt Chamberlain’s foot to

throw off his concentration?

“It doesn’t take much to misdirect the foe. Look at how Benny

Leonard merely touched opponents’ shoulders to distract them. Ninety per cent of

the ring result is mental, not physical. Fitz had an excellent brain and loads

of mental energy.

“Hank Kaplan picks Sam Langford over Fitz via Sam’s greater

mobility. Hank also believes that Harry Greb was the greatest and smartest

streetfighter and would have out-stepped Bob.

“Kaplan, no doubt, would see Roy Jones Jnr out-boxing and

out-slicking Fitz, and Charley Burley doing likewise. To me, Jones runs away

from Fitz all night long and loses by decision. I think too that Bob would have

outsmarted and overpowered Burley for a decision win. People forget that Fitz

found a way to beat the classiest and divine boxer in Jim Corbett.”

Historian and film collector Mike Hunnicut feels that Fitzsimmons

might have been as much as ten times better than believed by many members of

today’s boxing fraternity. “I love Fitz,” says Mike. “He was a fierce fighter

and possibly the hardest pound-for-pound hitter ever. He was a truly devastating

one-punch artist. One or two to the head or body and that would be it, even for

the toughest heavyweight. His were short and explosive blows that he could

deliver at any time and to any part of the body, whether off a cross counter or

by simply beating his man to the punch.

“Because so few fighters could stay in the exchanges with Bob, he

had to track them down and cut the ring off on them. That required great guile,

courage and quiet ferocity.”

Fitzsimmons v Sugar Ray!

Tracy Callis believes that Fitzsimmons was the all-time ace of

fighters and would beat Sugar Ray Robinson in a time tunnel showdown.

“Bob Fitzsimmons was a great fighter and a triple crown

undisputed champion. He was clever, shifty, quick of foot and a phenomenal

two-handed puncher. In my view, Fitz was the greatest pugilist who ever stepped

into the ring. On an all-time basis, I see him as the best middleweight ever,

the second best light-heavyweight behind the great Gene Tunney (Fitz won that

title when he was forty), and the greatest of them all on a pound-for-pound

basis.

“In today’s world, Sugar Ray Robinson is almost everyone’s choice

as the best pound-for-pound fighter ever. As good as Ray was, I believe that Bob

Fitzsimmons was better, both in a man-against-man match-up with Sugar and as a

pound-for-pound fighter.

“Fitz would have beaten everyone that Ray beat and would have

beaten Ray too. In a face-to-face contest, I believe Fitz would have handled

Robinson’s best punches, but that Ray could not have handled Bob’s.”

For Tracy Callis, another crucial factor here is the ability

Fitzsimmons had to carry his debilitating punching power through the weight

divisions.

“Many great fighters move up in weight class as the years pass.

As they do so, they find the competition against larger men more difficult to

handle. In fact they can move up only so far until they can no longer dominate

the way they did. Giving up 15-20lbs to their opponents becomes a monumental

task.

“As to Fitzsimmons, who else could give up 40lbs and still win

and dominate as Fitz did? Bob possessed ‘off the charts’ power for his weight.

“Some boxing fans of today find it hard to believe that a man of

Fitzsimmons’ size could do the damage he did to much larger men. Keith Robinson,

writing in the British Boxing Board of Control Yearbook 2005, took it a step

further and posed the question: ‘What if Fitz had been born in 1963 instead of

1863?’

“Considering today’s nutrition, Robinson wrote: “Our twentieth

century Bob Fitzsimmons would be a natural 199-pounder, retaining all the skill,

speed and power of the 1890s competitor. Surely this pound-for-pound Fitz would

be a match for any of today’s super-heavyweights.”

Special few

In this writer’s opinion, these are not fanciful suggestions. The

special few have a way of marking their territory very early in life. They show

you that indefinable quality that other souls simply do not possess.

In New Zealand, before he turned professional, the youthful 140lb

Fitzsimmons was already blazing a trail and leaving his audiences agog. When Jem

Mace, the grand old boxing master, journeyed to Bob’s adopted homeland to

organise a boxing tournament, the fans were witness to special event that wasn’t

in the script. What they beheld left them reeling.

Mace saw something special in a Maori heavyweight named Slade and

confidently pitched his protege against Fitz. There was certainly something

special in that ring that day, but it wasn’t Mr Slade. Fitzsimmons hammered him

so ferociously that Mace himself stopped the fight in the second round.

Fitz never did lose that God-given power. Right to the end of the

line, it remained as frighteningly concussive as his striking physique.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|