Hit By Briscoe: When

Bad Bennie Crushed The Golden Boy In Paris

By Mike Casey

Bennie

Briscoe, ever gracious and still mildly dazed by his violent night’s work, was

full of praise for Eugene (Cyclone) Hart’s left hook after their epic ten-rounds

draw. Bennie reckoned that Cyclone could knock down the walls of Jerusalem with

that punch if he had a mind to.

Hart was

no less impressed by the immovable object he had encountered. The Cyclone was

grateful, he said, to be back in the sanctuary of his dressing room and able to

talk about the fight. The way Briscoe had been hitting him, Hart figured he

might be going some place else.

So, then,

just another vicious, life-or-death war at the Spectrum in the Philadelphia of

1975. What was it like to be Bennie Briscoe? Well, for some twenty years, you

got to lay your life on the line by jousting with the likes of Mr Hart, Stanley

(Kitten) Hayward, Tom Bethea, Billy Douglas, Luis Rodriguez, Rodrigo Valdez,

Marvin Hagler, Carlos Monzon and Emile Griffith.

You got

one shot at the middleweight championship for all your hard labour and came up

short against an Argentinian iron man who chain-smoked his way through life and

might just have been inhuman.

But once

in a glorious while, you got to set off a mighty explosion that was heard around

the world….

Blessed

Had Tony

Mundine, Australia’s Aboriginal stylist, been blessed with a solid chin, we

might now be comparing his name to those of middleweight greats such as Mickey

Walker, Harry Greb, Sugar Ray Robinson or Carlos Monzon. During his peak years

in the early seventies, Mundine was a majestic boxer-puncher who seemed destined

for world championship success. When he journeyed to Paris in 1973 and

outpointed former five-times champion Emile Griffith, the fight media lavished

praise on the smooth-moving, skilful youngster.

By that

time, Griffith was past his best, but he was still a formidable campaigner, a

wise old general whom few men could outsmart. Mundine’s timely performance

pushed him into the top bracket of the middleweight rankings and suddenly the

world championship was within his reach.

At the

beginning of 1974, only one man stood between Mundine and world champion Carlos

Monzon, and that man was a source of worry to Mundine’s more sceptical critics.

His name was Bennie Briscoe, a tough and rugged thirty-year old slugger who had

campaigned against the world’s top middleweights in a colourful career that

spanned more than a decade.

Born in

Augusta, Georgia, but a product of the notoriously tough Philadelphia fight

school, Briscoe was a hard, ruthless puncher who always came to fight. His ring

reputation as a man of violence hardened the reservations of those observers who

had long doubted Mundine’s durability.

There were

two skeletons in Tony Mundine’s closet, two jarring defeats that had been so

sudden and emphatic that the balance of his record (44 wins and a draw) couldn’t

bury them. The first loss had occurred in 1969, Tony’s first year as a

professional and a mixed year for two of his illustrious countrymen. Johnny

Famechon won the world featherweight title from Jose Legra in January, but seven

months later, Lionel Rose, another greatly talented Aborigine, lost his

bantamweight championship on a fifth round knockout to the sensational young

Ruben Olivares.

Mundine

turned professional in March of that year and quickly impressed Aussie fight

fans as he reeled off ten successive wins in seven months. It seemed another

Australian world champion was in the making. Then the first bomb was dropped in

Melbourne on November 10, and the seeds of doubt were sewn. Matched with Kahu

Mahanga, a less talented but hard punching prospect, Mundine was shockingly

knocked out in the ninth round. Had Tony been stopped on his feet or forced out

of the fight by an injury, he might have been spared a further mauling by his

critics. But he was counted out and the vultures always begin to circle when a

coming boy is crushed so comprehensively.

A

fighter’s chin is one of the most important yardsticks of his potential, because

ruggedness and endurance are such essential ingredients in the fight game. Those

men devoid of natural skill, those who don’t possess a knockout punch or an

innate gift for slipping and blocking, are recognised as lacking in special

qualities, yet their limitations rarely incite panic. But a man with a

susceptible chin is so often administered the last rites before he is even out

of the starting blocks.

Managers,

trainers and fans quietly dread that first time when a young fighter has his

chin tested, because his reaction can instantly foretell his future in the

sport. The special few, such as the unlucky and those in the wrong place at the

wrong time, can meet with violent defeat and survive the crisis. But not those

whose weakness is inherent and permanent. They can only bluff and duck and weave

their way to the highest point on the ladder they can reach.

On the

surface, Mundine didn’t appear badly affected by his defeat to Mahanga. Tony

quickly returned to his winning ways with a knockout victory of his own just a

month later. Indeed, his confidence seemed higher than ever the following year

as he combined skill and power to restore the faith of his supporters by

chalking up eight consecutive wins inside the distance.

In January

1971, he challenged Bunny Sterling for the Commonwealth title in Sydney, and

looked impressive in forcing the evasive, underrated Sterling to a 15-rounds

draw. It seemed that Mundine was on his way, but then came another bolt out of

the blue. He was matched with veteran contender and former world welterweight

champion Luis Rodriguez in Melbourne, and once again Tony’s vulnerability was

exposed as he was sensationally blasted out inside a round.

It was a

damaging reverse for Mundine. For while Rodriguez was still a top class

campaigner, he was considered ripe for the taking after suffering a stunning

knockout defeat to world champion Nino Benvenuti a year earlier. How far had

Rodriguez gone back? Just a month after his decimation of Mundine, Luis

travelled to the Royal Albert Hall in London, where he looked awful in dropping

a points verdict to Bunny Sterling. The prime Rodriguez had plainly disappeared

over the horizon. He looked badly trained, off balance and his reflexes were

poor. The defeat sent Luis tumbling from third to fifth in The Ring magazine’s

revised ratings, but he should have been lower. He was all but gone as a world

class force.

Now Tony

Mundine had to answer his critics all over again. He had been blitzed by a jaded

maestro who should have been little more than a stepping stone.

A first

round knockout loss is arguably the ultimate humiliation for a boxer. Confidence

is eroded and despondency can quickly set in. The victim is not only haunted by

his own mistakes, but by the withering verdicts of those who sit and judge him.

And, of course, ‘golden boys’ like Mundine get the stick more than most others,

mostly in the form of sledgehammer sarcasm from the ivory tower pundits who only

bleed when they are careless shaving.

Mundine,

however, was a strange animal and one to be greatly admired. The bitter irony in

his case was that his attitude to adversity had all the steel and resistance

that his jawbone lacked. Far from causing him to lose heart, defeat seemed to

spur him to greater effort and commitment. Such is fate, he proceeded to enter

the finest phase of his career as he compiled a sparkling run of twenty-one

successive victories that elevated him into world championship contention.

In a

return match with Bunny Sterling, Tony scored a thrilling final round triumph to

win the Commonwealth title. Then he punched with authority to stop such

respected men as Denny Moyer, Juarez DeLima, Matt Donovan, Luis Vinales and

Nessim (Max) Cohen.

For good

measure, Mundine even stepped up a couple of weights to win the Australian

heavyweight title from Foster Bibron. Mundine was on a roll and when he capped

his 1973 campaign with his highly acclaimed victory over Griffith in Paris, the

stage was set for Tony’s final drive towards a world title challenge.

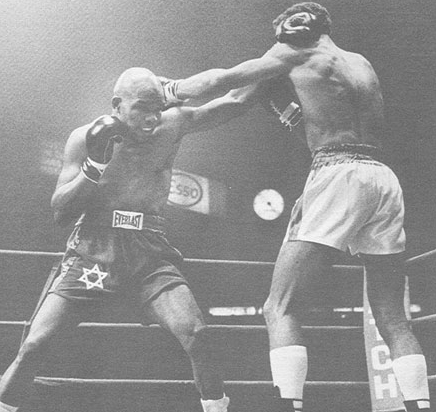

On

February 25, 1974, he was back in Paris again to confront the formidable

Briscoe, and the public’s imagination was caught. It was a pairing of two of the

world’s most exciting middleweights, a young lion against a battle-scarred,

street-fighting tiger.

Characters

Bennie

Briscoe was one of the game’s great characters, whose imposing, shaven-skulled

appearance complemented his simple and brutal fighting style. Like so many

hardened ring mechanics from poor backgrounds, Bennie’s career read like

fiction. His aggressive, uncompromising style was a legacy of his wild days as a

youth. As a fourteen-year old newcomer to Philadelphia, he joined a teenage gang

and inevitably got into trouble with the law.

A local

parole officer advised Briscoe to take up boxing and Bennie quickly took a shine

to the sport. He became a US amateur champion and was good enough to be selected

as a reserve for the 1960 American Olympic squad in Rome. But it was in the

professional ranks that he made his name and acquired his reputation as a man to

be feared.

Briscoe

turned pro in 1962, and through the sixties and seventies he met the best talent

in his domain. He seemed to labour for an eternity before establishing himself

as one of the division’s top contenders Bennie was always dangerous, but he

could be foiled by the more scientific boxers and dropped a number of decisions

on his way up the ladder. It is a worrying sign of how things have changed that

such educational defeats were not frowned upon in Bennie’s era. Indeed, they

were rightly seen as positive grist to the mill if the beaten fighter learned

from his mistakes and doubled his reserve.

Win or

lose, Briscoe was a physically and mentally tough cookie who never gave up and

who personified excitement. As he progressed up the ladder in his gloriously

determined way, so his record became sprinkled with the kind of fights that fans

love to recall. His fiercely contested duel with the highly regarded Stanley

(Kitten) Hayward in 1965 was a case in point.

Bennie was

apparently instructed to ‘box’ Hayward for the first seven rounds of their

scheduled ten-rounds encounter and fell some way behind on points. From the

eighth round, the game plan was belatedly revised and Bennie was told to go out

there slugging. He gave Hayward such a beating that Stan was taken to hospital

with concussion. Alas, the big charge came too late and Briscoe dropped a split

decision.

Bennie had

also been involved in a short-lived but violent encounter with another renowned

puncher, Mexican Rafael Gutierrez, in which Briscoe survived a rocky first

session to score a dramatic second round knockout. It was a slugfest that was

rife with controversy.

Hitting

the tank-like Briscoe broke Gutierrez’s right hand and bruised his left, but

Rafael came close to breaking the bank in a whirlwind first round when he decked

Bennie twice with vicious rights to the head. The pendulum swung back to Biscoe

when he clearly hurt Gutierrez with a body punch on the bell.

Gutierrez

was being handled by Sid Tenner, a Sacramento furniture dealer, who insisted

that Briscoe’s punch was low and that Rafael was in no fit condition to come out

for the second round. Whatever the truth of the incident, Bad Bennie was the

consummate pro as ever and quickly finished the job. He sank another right into

Gutierrez’s body and put him down for the count.

Sid Tenner

was not a happy man. “I wish now I would have held him (Gutierrez) back and

protested the fight – but I know how far that would have got me. We got zilched

– very bad.”

By the

spring of 1972, Boxing Illustrated magazine rated Bennie Briscoe the number one

middleweight contender to Carlos Monzon’s world championship, ahead of Emile

Griffith, Denny Moyer and Frenchman Jean-Claude Bouttier.

Bennie was

in blistering form and showing his opponents no mercy. Earlier that year he had

ruthlessly despatched Buffalo’s Al Quinney in two rounds at the Philadelphia

Arena. The scheduled 10-rounder featured something of a surprise in the opening

round, as the tall Quinney clearly fancied his chances against Bad Bennie and

tried to seize the whip hand. Jabbing and firing right crosses, Al quickly

discovered, much like Rafael Gutierrez, that Briscoe’s head could be as damaging

as his fists. Scoring with a right, Quinney split his glove and had to pause for

a replacement.

It was an

ill-timed intermission for Al. One can only imagine that the time-out made

Bennie irritable, for he promptly steamed into the attack when the battle

re-commenced. A beefy right to the jaw sent Quinney tumbling for a count of nine

and there was no reason to believe that the scheduled minute’s rest would save

him.

Briscoe,

coming into the ring at an even 160lbs, was all business in the second round.

The game Quinney continued to pump out the jab but quickly began to resemble a

man trying to extinguish a fire with a water pistol. Another right to the jaw

crashed home from Bennie and another nine count followed for Al.

John

Lennon once had a number nine dream, but poor Quinney was having a number nine

nightmare. A right uppercut spilled him once more for as many seconds. Lanky Al

never stopped trying to survive, but he finally reached the number ten when

Briscoe’s final assault culminated in the payoff punch, a slamming overhand

right to the jaw.

Reservations

One could

understand why so many of Tony Mundine’s supporters harboured serious

reservations about their man going in with Bennie Briscoe. A powerful left

hooker, Briscoe’s punching power and determination had brought him victory

against a string of high ranking contenders and tough journeymen. Quality

fighters such as Art Hernandez, Tom Bethea, Carlos Marks and Juarez DeLima had

failed to subdue Bennie, while Briscoe’s supporters will forever remember their

man’s epic eights rounds victory over the tough Billy (Dynamite) Douglas for the

North American championship.

While Tony

Mundine’s durability was suspect, Briscoe’s had never been questioned. Bennie

traded heavily on his toughness, and a condition of his no-nonsense attacking

style was that he was able to absorb punishment. He was one of the few men whose

strength and ruggedness nearly rivalled that of the mighty Carlos Monzon, and

Bennie twice took Monzon the distance in gruelling fights. The two iron men drew

over ten rounds when they were both rising contenders in 1967 and it would be

five years before they came together again. By that time, Carlos was the king of

the division. Briscoe, ten months after his quick victory over Al Quinney, gave

Monzon a spirited challenge before being outpointed in a stirring battle.

As he

prepared himself for his meeting with Mundine, Briscoe knew he needed a

convincing victory to re-establish himself as a threat to Monzon. Five months

previously, Bennie had lost ground in the world rankings after being narrowly

outpointed by the fast improving Rodrigo Valdez.

But

Briscoe had that rare ability to change his fortunes with one sudden explosion

of power, his record serving as a chilling reminder of his punching prowess. In

a 62-fight career, he had knocked out or stopped 41 of his 48 victims. Mundine’s

supporters and critics knew that this was the man to make or break the young

Australian.

Superb

Both

fighters were in superb condition for their eagerly awaited contest. As they

joined battle, the packed Palais Des Sports Arena in Paris crackled with that

special air of excitement that is synonymous with big fight occasions.

Briscoe’s

game plan was to pressure Mundine, just as Bennie pressured every opponent. The

Philadelphian looked menacing and purposeful as he marched forward, gloves held

high. But it was Mundine who caught the eye as he set about the most demanding

task of his career in a sure and confident manner.

One might

have expected Tony to start cautiously in view of Briscoe’s reputation and the

crucial importance of the battle. Yet there was almost a touch of arrogance

about Mundine’s work as he peppered his oncoming opponent with rapid jabs and

followed up in style with hooks and uppercuts. On more than one occasion in

those opening minutes, Mundine’s silky, evasive skills had Bennie missing badly,

but Briscoe continued to press forward, as if mechanically geared to move

exclusively in that direction. He struggled to find the range, but when his

punches did connect, they looked solid and hurtful.

However,

the early advantage definitely belonged to Mundine. In the second round, the

Australian produced some of his finest boxing as he repeatedly checked Briscoe’s

advances with beautifully precise counter punches. Tony was keeping just the

right distance between himself and Bennie, a safe but effective distance that

still enabled the versatile youngster to strike home with his own blows.

Both

fighters had now warmed to the job at hand, and the hard punches gradually began

to fly. Mundine’s jaw underwent its first serious examination as Briscoe scored

with a pair of heavy rights, but Tony took the blows well and rallied back to

stun Bennie later in the round with a hard right uppercut.

As the

gripping duel progressed, the tension increased and so too did one’s admiration

of both fighters. They differed so much in style, yet each possessed that

certain touch of class that distinguishes the top-flight ringmen. Mundine’s

boxing was a joy to watch, and though Briscoe’s approach was far more primitive,

it was no less entrancing.

Blood

flowed in the third round as both fighters suddenly sported cuts over the right

eye, but it was Mundine who seemed perturbed by this sudden development.

Initially, his injury appeared to have no effect on the quality of his work as

he continued to fence cleverly with Briscoe. However, as the fight moved into

the fourth round, it was noticeable that Bennie was beginning to have more

success with his bulling, hustling tactics. He punched hard to the body and

looked increasingly threatening with long rights to the head, one of which

appeared to stagger Tony.

Mundine

looked uncomfortable whenever Briscoe found his way inside, but Tony’s punch

rate was still superior to Bennie’s. With the fight approaching the halfway

stage, Mundine was a good way ahead on points.

As the

fifth round opened, the cat-and-mouse game was becoming ever more intriguing

when Briscoe suddenly struck with a hard right to the chin that tipped the

scales dramatically in his favour. Mundine’s legs quivered under the force of

the blow and Bennie saw the chance for which he had been so patiently searching.

He surged forward, forcing Mundine against the ropes and driving in wicked blows

to the head and body as Tony desperately sought a way out of the trap.

Hunter

Briscoe

was now in his element, a hunter at last in charge of his prey, and one could

see Mundine wilting as Bennie seized his chance with clinical efficiency. Unable

to turn the tide, Tony sank to one knee, his head and right arm outside the

ropes, as referee Paul Tallyrach moved in to start the count. It was a count

Mundine failed to beat.

The

Australian’s collapse was a sad spectacle. It confirmed people’s worst fears

that, for all his marvellous talent, Tony Mundine did not have the physical

make-up to survive and prosper at the giddiest heights. Briscoe was blessed with

that special quality, and there was the difference.

Evergreen

Bennie, with his usual brand of controlled violence, had once again surfaced to

cast his ominous shadow over the world middleweight championship.

In that

romantic city that runs the gamut of human emotions, it had truly been a night

of heartbreak and joy.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|