Benny Leonard: Golden Talent of a Golden Age

By Mike Casey

In his new book, The Arc of Boxing, my fellow historian Mike

Silver has produced a masterful study of the rise and decline of the great sport

we once knew as the Noble Art. Mr Silver sets out by drawing a definitive line

in the sand and argues his case from that boundary. He does so with eloquence

and great truth. Very simply, he believes that boxing’s golden age ran from

approximately 1925 to 1955 and that we have seen nothing but a steady and

depressing dilution of quality and knowledge ever since. He is quite correct and

I salute his courage for stating his case and fending off the ‘my way or the

highway’ crowd who choose to shield their eyes and plug their ears for fear that

their own fragile reasoning might be shot to pieces.

I have been saying for longer than I care to remember that the

once great discipline of boxing has long been shed of its golden robe. Its

priceless secrets have been forgotten, shunned or watered down into meaningless

sound bites by too many trainers of dubious qualifications and too many fighters

of pedestrian talent. It is of some consolation to me that I have a small band

of brothers who are kind enough to remind me from time to time that I am not

mad, deluded or old enough at 52 to be classed as prematurely senile.

Boxing analyst

Mike Hunnicut, who has studied and patiently analysed dozens of fight films from

all eras, explains some of the major reasons for the slow demise of technical

quality and versatility: “From

the mid 1950s until the 1960s, many professional fight club venues began to

close. Boxers began to get more experience in the amateur ranks and turn

professional at later age. Often acquiring 100 amateur bouts, most boxers

received most of their experience as well as skills, in the amateurs.

Combination punching, headhunting, lateral movement became increasingly

emphasized while infighting, body punching, short and short middle range

techniques, compact punching and a mixture of fighting and boxing began to

erode.

“What was once fluidity and

adaptation in bouts in overall offense and defensive skills had become

predictable and rigid. Head shots with combinations tended to be the main course

of action as one opponent would throw his combination and then his opponent his.

This comparative lack of style and technical versatility remains today, as while

there are many great exceptions to this strategy, there is no doubt in objective

observation that prevailing ‘amateur’ style has produced less well rounded

performers and performances.”

Now let us talk of Benny Leonard, for there are many relevant

reasons to do so. Those who don’t know much about Benny really shouldn’t go

throwing stones in glass houses. So let me hand the stage back to Mike Silver

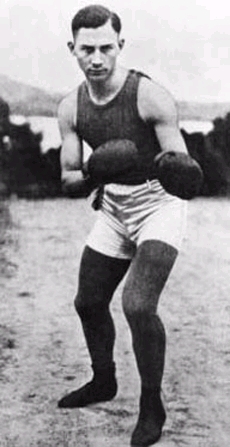

for the official introduction on Leonard from The Arc of Boxing: “Benny Leonard

used the same stand-up fencer’s stance as Jack Johnson, but employed a great

deal more footwork and speed (after all, he was 70 pounds lighter than Johnson).

Leonard took the science of pugilism to another level entirely. He fought as if

playing a physical game of chess in which the object was always to be mentally

and physically one step ahead of an opponent. Fighting on his toes, he jabbed,

circled and sidestepped. He ducked, rolled, slid in, slid out and feinted – all

the while looking to create openings for a variety of punches.

“A skilled infighter, Leonard was just as formidable at close

quarters as he was at long range. He was also famous for the accuracy and timing

of his punches. Leonard’s proud boast was that no fighter could muss his hair in

a fight.”

Analytical

Benny Leonard was one of the great students of the game,

possessed of a brilliantly analytical mind. He is comparable in so many ways to

his illustrious predecessor, the Old Master himself, Joe Gans. Joe shared

similar gifts of perception, anticipation and what so often appeared to be

effortless execution. Benny and Joe were never too proud to study other boxers

and root out little gems of information. Both men were master boxers, but, more

importantly perhaps, master thinkers. It remains almost impossible to state with

any great degree of conviction who was the greater of the two. Leonard was

faster and undoubtedly fitter. Let us not forget that Joe was already being

dogged by ill health in the last years of his prime as well as handicapped by

the odious circumstances of his day. Yet still he was fighting off the other

titans of the era.

In his savage marathon with Battling Nelson in the searing heat

of Goldfield, Gans weighed 133lbs stripped before being required to make the

same weight in his street clothes following a cynical, additional clause

demanded by Bat’s handlers. Weight drained to a potentially fatal extent, the

already ailing Gans vomited a number of times between rounds.

Leonard and Gans were cerebral brothers in an age when every

trick of their dangerous profession needed to be mastered by any boxer who

yearned to be the king of the hill. They possessed an insatiable thirst for

knowing the answers to every question and taking their already formidable skills

to higher levels. For such men, the great and ever elusive search is for

perfection. No athlete ever attains this Holy Grail of course. But the special

few get tantalisingly close to it.

It is said that golfer Ben Hogan, whilst recovering from his

famous and near fatal car crash, woke up in hospital one night in a terrible

mood after a vivid dream. He had dreamt that he had birdied seventeen holes in

succession and then seen his birdie putt at the eighteenth lip out. That one

little miss, in Hogan’s view, had rendered all his previous brilliance

redundant. Ben wasn’t being trendily obscure when he said in later years that

the greatest golf swing he had ever seen was that of an unknown golfer on a

driving range. Hogan watched all sorts of golfers and all sorts of swings in his

belief that something could always be learned even from the unlikeliest of

sources.

Benny Leonard and Joe Gans possessed similarly inquisitive minds

and the ability to assimilate and act upon the information they absorbed. Such

was the similarity of their range of skills, we could often be talking of the

same boxer. Both men were wonderfully correct hitters (a not so obvious art in

itself). They knew everything about proper weight transference, perfect balance

and always being ready to strike. They mastered the disciplines of leverage,

pivoting, timing, snap, slipping, blocking and feinting. They studied human

behaviour and how quickly the brain of an opponent could be scrambled and

gridlocked. Leonard would give his foes a little tap on the shoulder at

appropriate moments to disorientate them. An old trick, yes, but a boxer of

Leonard’s quality could amplify its effectiveness no end.

What else bound Benny Leonard and Joe Gans together? Toughness,

grit and great courage when the tide turned against them. Both were tried and

tested many times and neither was found wanting in the prime of their careers.

Soldier Bartfield

Benny Leonard and legendary trainer Mannie Seamon virtually lived

at the famous old Grupp’s gymnasium in New York during Benny’s glory days. Said

Benny, “I must spend eight hours a day in Grupp’s, it’s my place of business.”

One fine day, when Benny had finished his training session, he

and Seamon were watching Soldier Bartfield working out. Leonard gave Seamon a

little nudge and said, “Bartfield’s dropping his left hand every time he jabs.

Anybody could drop him with one shot.” Bartfield didn’t appreciate this

observation at all when it was inevitably relayed back to him. “What are you

trying to make a clown out of me for?” he yelled at Leonard.

Benny’s response only stoked things up: “That’s not hard.”

The two men hade it out in the ring and what followed was a

painful experience for Bartfield. Moving into Leonard with bad intent, Soldier

sent out a range finding jab and Leonard countered it with a hard and fast

right. Bartfield’s legs turned to jelly, but the message was still lost on him.

He jabbed again and another snapping right bowled him over. Leonard looked at

Mannie Seamon and said, “The lesson’s wasted. Wait for me, we’ll be leaving for

downtown in a few moments.”

When trawling through his extensive collection of fight films,

Mike Hunnicut never cease to be in awe of Benny Leonard’s many gifts. “Leonard,

along with one other boxer, is my all time favourite to watch, study and enjoy

on film,” says Mike. “There is so much to appreciate, it’s impossible to get

bored. His balance was simply impeccable. If there is one thing that all good

boxers must do in their daily ring work – right to the time they hang up their

gloves – it is to slowly and conscientiously work on their balance. Some boxers

never attain good balance, because it is not easy to do.

“Leonard was as good as it got at this discipline. Linked with

this balance was incredible footwork. You never really knew where he was, he was

always in and out, to the left and to the right, back in and then out to the

left or right again, circling and mixing it all up in mysterious ways. He had

his great jab with great combinations and a wicked punch. And Leonard could

feint you with every part of his body. Jimmy McLarnin once remarked that his

eyeballs nearly popped out of his head the first time Leonard really feinted

him.

“You can almost see the wheels turning as Benny puts everything

together whilst studying his opponent with never surpassed boxing skill, ring

intelligence and generalship, tempered against incedible opposition. Benny

Leonard may have become the greatest fighter that ever lived.”

Gambler

It is important to establish that while Benny Leonard knew all

the evasive tricks, he wasn’t a ‘runner’, any more than was Joe Gans. Along with

the great care and precision that Benny brought to his ringcraft was the

essential nerve of the gambler. When Leonard saw his chance to end an evening’s

work inside schedule, he rarely paused to smell the roses for a while longer.

His lightning fast right hand would shoot from his chest like a snake’s tongue

when his intuitive brain told him the time was right. He loved the challenge of

being the first to draw in a battle of wits, waiting for the opponent to lead

before stepping inside with that devastating right counter.

Leonard’s judgement of distance was uncanny. This is an

instinctive and innate gift among the true greats of any profession, who never

seem plagued by the necessity to clutter their heads with pre-set plays or mind

triggers. Centuries ago, a doubter asked Giotto, the famous Italian artist who

started life as a shepherd’s boy, to prove his genius. Giotto responded

instantly by picking up his brush and painting a perfect circle. In one

brilliantly impudent move, he proved himself not only a genius painter but also

a genius draughtsman. Benny Leonard, in the earthier and more urgent arena of

the Noble Art, would frequently perform similar tricks. When that countering

right hit the mark, it generally did so with machine-like accuracy.

This is not to say that Leonard was never caught out. They all

are from time to time. But that famously acute brain, along with plain old

fighting courage, proved equally adept at getting him out of a hole. Richie

Mitchell struck first and had Benny seriously on Queer Street in the first round

of their barn-burner of a fight at Madison Square Garden in 1921, but Leonard

dug himself out of the mire to stop Richie in the sixth. Six months earlier, at

Benton Harbor in Michigan, Chicago great Charley White tested his famous left

hook on Benny and very nearly knocked the maestro out. But it was Charley who

took the full count in round nine.

Lew Tendler was another who glimpsed everlasting fame against

Leonard before coming back to earth. In the first battle between the two men at

Jersey City in 1922, Tendler, one of the greatest southpaws ever, had Benny in

desperate trouble. Employing classic kidology, Leonard wriggled from the crisis

by talking Lew into a state of self doubt and uncertainty. The fight was a close

affair in the days of newspaper decisions, but most felt that crafty Benny had

edged home after 12 lively rounds.

Arguably, the young Leonard gave his greatest exhibition of raw

fighting courage in surviving terrible punishment to outlast one Evert Ivar

Hammer, a remarkable tough Scandinavian brawler who carried the strangely

chilling and appropriate ring name of Ever Hammer. Head down and smashing away

to Benny’s body all the time, Hammer would have broken most other fighters that

night with his near suicidal assaults. With great heart and soul, Leonard

emphatically endorsed the old adage that appearances can be deceptive. Dapper he

certainly was. Lacking in toughness and courage he certainly wasn’t.

To Leonard, this was all business and nothing more. He had little

time for the term, ‘killer instinct’, which had entered the boxing language in

earnest on the heels of his great contemporary, Jack Dempsey. “I don’t want to

hurt the other guy,” Benny once said. “I want to stop him. But that does not

mean I am eager to cut him up and murder his self respect. The credo of the

professional ring is to win with speed and your best means of execution. As for

that ‘killer instinct’, I never had it as a kid when bringing home the pay was

very important, and I never had it as a champion.

“I have read a lot of stuff about Jack Dempsey and his killer

instinct. Well, that guy really is a softie. Killer instinct left boxing with

bare knuckles and so-called revenge fights. I never sought a revenge bout in my

career, not even when they offered me return fights with Mickey Finnegan, Joe

Shugrue and Frankie Fleming, the only lightweights who stopped me during the

first three years of my career.”

Many felt that Benny ‘carried’ Rocky Kansas, for whatever

reasons, in a lightweight championship defence at Madison Square Garden in

February, 1922. In the eleventh round of their 15-rounds match, Leonard unhinged

the teak-tough Kansas with a cracking left hook to the chin, but appeared to

make no concerted effort to chase the knockout. Quite to the contrary, Benny’s

famous punching accuracy seemed to mysteriously desert him as he repeatedly

missed Rocky by fractions for the remainder of the fight, prompting ringside

reporter Damon Runyon to wryly observe, “It takes as much skill to miss by just

so much as it does to hit.”

The natives were not amused. Disgruntled members of the crowd

pointed out that the betting was 2 to 1 on Benny knocking out Kansas inside 10

rounds, but then switched to 5 to 1 at the eleventh hour on Kansas not being

knocked out. Well, something might indeed have been going on. But as Runyon

reminded his readers, “Rocky Kansas is as tough as rawhide. No one knocks him

out. A man can break his hands battering at the marble chin and the iron flanks

of the Buffalo Italian. It may be that his amazing stamina was keeping him afoot

in the eleventh round rather than any deliberate inefficiency on the part of

Leonard.

“It is an old cry among Leonard’s following, a cry that he

himself resents, that any time Benny fails to stop an opponent he is ‘carrying’

him. Sometimes it is a great injustice to his opponent.”

However, five months later, as if to prove a mischievous point,

Leonard pierced the marble chin and the iron flanks of Rocky Kansas by stopping

him in eight rounds.

Return to Tendler

Almost exactly a year after letting Benny Leonard off the hook in

their first fight for Benny’s world title in Jersey City, Lew Tendler must have

felt confident about his chances gong into the return match at Yankee Stadium on

July 23, 1923. Lew was a tough and dangerous man of his hard era. Still two

months shy of his 25th birthday, he had already been a pro for nearly

10 years after making his debut as a 15-year old. More than 120 fights adorned

his sprawling record, of which he had lost just three legitimately. A shrewd

southpaw with a hammer of a left cross, it was Tendler’s unfortunate destiny to

be Leonard’s contemporary.

There was no joy for Lew at Yankee Stadium. In fact Benny barely

left him a scrap with which to console himself. It was one of Leonard’s finest

nights as he showed the full range of his skills to some 65,000 customers paying

half a million dollars. Some attendance for a couple of small fellows, eh? That

was boxing in the Roaring Twenties. Right from the off, poor Lew was chasing a

ghost that wasn’t at all reticent and could make contact into the bargain. And

how Benny made contact. Tendler tried manfully to wreak damage with his famous

left hook, but found the experience as fruitless as trying to thread a baseball

bat through the eye of a needle. All the while he was being struck every which

way by Leonard’s unerringly accurate punches. Tendler was quickly made to look

like a novice and he was anything but that. It took him a good six rounds to

strike Benny with a meaningful blow. In his mounting frustration, Tendler’s work

grew ever wilder as he missed repeatedly with despairing rights and lefts.

Leonard’s evasive skills and precise counter punching were majestic. Lew, to his

great credit, never stopped hunting Leonard in the hope of finding one magical

punch that would turn the fight upside down. All too often, however, the game

challenger looked like a man trying to fend off a hail of stones.

Benny’s cultured attack was ever varied. He jabbed, hooked and

moved around like a man on castors as he worked both the head and body. In the

13th round, a powerful left hook to the stomach had Tendler in

distress and he went to his knees shortly afterwards from a flurry of blows as

the two boys were engaging in a torrid exchange. In an age where boxing fans

didn’t enjoy the technical luxuries of replays and pos analysis, Leonard’s more

subtle inside work (much like that of Jack Dempsey) was often missed and

unappreciated. The telling punches would be fired short and fast and the

opponent would suddenly be disabled.

The courageous Tendler survived to the final bell, but only in

the way of a man staggering through a blizzard as Leonard drilled home punches

from all angles. One reporter described Lew’s plight thus: “He did not seem able

to hit a barn door with a handful of buckshot.”

The Coronation

Before the reign of Benny Leonard, there was the reign of the

great Freddie Welsh, who appropriately hailed from Wales and was acknowledged as

the master of the left jab. Freddie was a boxing wonder in his own right, as

well as being an astute and canny observer of his prospective opponents. He kept

a constant eye on those who might be capable of storming his castle. Welsh

quickly recognised Benny Leonard as the most talented and dangerous of the

contenders and began to put out feelers.

In the days when world champions were afforded greater protection

and leeway, Freddie made the common decision to test the water without putting

his crown on the line. He engaged Leonard twice in 1916, first at Madison Square

Garden in March and then in Brooklyn in July. It was apparent from those

meetings (so often described as chess matches) that Welsh and Leonard were the

two titans of the lightweight division. The general consensus was that Benny

edged the first affair at the Garden, but Freddie was hailed by most as the

clear winner of their Brooklyn engagement as he opened up his box of tricks and

showed Leonard much more. Perhaps that was the champion’s mistake, for many

believed that Benny was keeping his heavier artillery under wraps that night.

Welsh was still covering his back when the two men clashed in

earnest for the third and final time in New York on May 28, 1917. Very simply,

Benny had to stop Freddie to win the championship. At 31, Welsh was almost

exactly 10 years older than Leonard and an ‘old’ campaigner by the ferocious

standards of the day. But beating Freddie was still a mighty order.

Pasty faced and willowy limbed, there was an oddly intimidating

air about Welsh when he went into battle. Brilliantly schooled in all areas of

the game, he would often wear a confident smile that was more of a sneer. He

would sway gently from the hips, always protecting his chin, looking a picture

of assurance. He surely couldn’t have anticipated the storm that was to follow,

for this was a different Benny Leonard who laid his best cards on the table from

the outset and dared Welsh to better the glittering hand. A younger and fresher

phenomenon was about to trump the fading king.

Leonard set a cracking pace and made Welsh’s lean body the

principal target. Punching hard and fast, Benny fired in accurate shots to the

ribs and stomachs as he pursued Freddie constantly. Seeking to smash through the

champion’s ring of confidence, the sprightly challenger cheekily stuck out his

chin as an inviting target. Welsh was a boxer who rarely miscued tactically, but

now he was being lured into errors by a similarly clever and agile mind. In the

fourth round, Leonard nailed him with that flashing right counter that would

become a potent trademark of the brilliant New Yorker. Freddie’s head was thrown

back and his knees dipped from the force of the blow. He couldn’t make his legs

work for a few desperate seconds, but then he showed all his ring savvy as he

bluffed and hustled his way through the crisis.

But Benny had made a big statement and severely shaken Welsh’s

great confidence. Freddie was still wearing that odd, mocking little smile when

he joined battle for the fifth round, but now he knew for sure that the new kid

in town was seriously knocking on the door. A quite definitive pattern was now

taking shape. While Welsh’s famous left jab was still scoring points for him (he

rarely missed anyone with that textbook blow), Leonard’s punches were

considerably more destructive. After eight rounds, those educated punches of the

Jewish ace had all but drained the resistance out of a grand champion. Welsh was

for the taking and Leonard knew it. He was on Freddie in a flash at the start of

the ninth, knocking the Welshman down with a right that cut straight through his

defence. Stubborn pride got the better of Welsh, who jumped up without taking a

count and walked straight into a firestorm.

Leonard knew it was his hour and swept straight through Freddie’s

brave defiance, cutting him down for the second time with another cracking

right. It was a blow that sent Freddie’s mind into an inescapable fog. He was an

easy target when he got to his feet and the final driving blow from Benny – a

left this time – left the broken champion in an eerie limbo. Somehow he remained

upright, but he was gone as he grabbed the ropes and staggered drunkenly against

them. Leonard moved in to apply the coup de grace, but the referee intervened

and stopped the fight just as it seemed that Welsh would tumble through the

ropes.

A glorious reign had ended. And the fabulous era of Benny Leonard

had begun.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|