Breathtaking: The 10-Month Triple Title Blitz of Homicide Hank

By Mike Casey

A man asked me

recently how great Jack Nicklaus was. Pressed for time, I told him to look up

Jack’s record, study it carefully and put it into perspective with regard to the

tools he had at his disposal in a far less technical era.

My answer is

pretty much the same when I am asked about Henry Armstrong. I do not dole out

such advice willy-nilly, since we know that the record book is not always a

wholly accurate judge of a sportsman’s talent and achievements. In boxing, this

is particularly the case.

It’s just a nice

fact of life that the truly great fighters have truly great records that do not

generally mislead us. Now look at the sprawling record of Henry Armstrong and

look at the names of the men he fought and defeated. If you do not know those

names, if you do not know the circumstances and cannot be bothered to acquaint

yourself with their significance, then you really shouldn’t ask the question.

In the days of

eight traditional weight divisions and only one world champion presiding over

each of them (yes, junior, such a pleasant state of affairs did once exist in

our violent and unprincipled little arena), Henry Armstrong won the

featherweight, welterweight and lightweight championships in that order. In

doing so, he defeated Petey Sarron, Barney Ross and Lou Ambers respectively in

the space of ten months.

Not bad for a

starting reference point, eh? But before we start throwing around the names of

Henry’s many other illustrious opponents, let us revisit that important word,

‘perspective’.

Armstrong, in

the almost unanimous opinion of my esteemed fellow historians, was never a more

destructive force in the ring than when he reigned in his natural domain of the

featherweight class. I concur fully. Henry never truly stopped being a

featherweight, hence the magnitude of his achievements. He blistered his way

through that division before wrecking Petey Sarron with a single punch to win

the world crown.

Yet more often

than not, Armstrong is classified as a welterweight in the various all-time

rankings due to his multiple defences of the 147lb crown. Winning that

championship from another all-time ace in the wonderful Barney Ross, Henry

defended it eighteen times in the stunningly short space of seventeen months

before he finally ran out of gas and bowed to Fritzie Zivic in two brutal

contests.

In the midst of

his barnstorming welterweight reign, Armstrong gave Lou Ambers the chance to

regain the lightweight crown. Lou did so on a highly controversial decision,

snapping a 46-fight win streak for Henry.

Fouling,

especially low blows, would cost Henry a great many penalty points throughout

his career, and he was punished severely by referee Arthur Donovan in this

return match with Ambers. All of five rounds were taken away from Armstrong, yet

neutral observers still had him winning the fight handily.

Among their

ranks was the steaming Henry McLemore of the Associated Press, who handed

referee Donovan the following prosaic pillorying: “Arthur Donovan is the new

lightweight boxing champion of the world. He is a bit fat for the title,

particularly in the head. But he won it in Yankee Stadium last night. He won it

for Lou Ambers by rendering a decision as questionable as a mongrel’s

paternity.”

Stunning

Why are these

latter achievements of Armstrong’s so stunning? Because in the opinion of many

writers of the day, Henry was on the wane when he stepped up to begin that grand

and prolonged assault on bigger men. He had already campaigned with almost

ridiculous regularity against umpteen world class opponents. By the time he

graduated from the featherweights, he had compiled what would now be regarded as

a career’s worth of fights and then some.

His high-octane

style of relentless attacking required him to work virtually flat-out for every

round. That many fights and that brand of commitment eventually erode the skills

and durability of even the hardest cases. The old-time writers felt similarly

about Mickey Walker when he graduated from the welterweights to the

middleweights. Mick was jaded, they said, shop-worn, over the hill. That is hard

for us to believe when we examine Magnificent Mick’s achievements thereafter.

Such was the extraordinary toughness and resilience of men like Walker and

Armstrong.

Henry, like most

fighters of his era, quite probably had more fights than his official career

count of 180. Of those we know, courtesy of those admirable and tireless

gentlemen from BoxRec, Armstrong won 149 and achieved a knockout total of either

100 or 101. When Henry was way over the hill, he was outpointed by his young

admirer, Sugar Ray Robinson, at Madison Square Garden. Robinson waged a

retreating battle out of respect to his idol, claiming that he didn’t wish to

hurt Armstrong. The compliment wasn’t greatly appreciated by Henry, who argued

that Robbie retreated out of fear!

As to the

overall quality of Armstrong’s opposition, well, if some of the aforementioned

names aren’t enough for you, there are plenty of others to pick from. Henry’s

ongoing series with the fiery and dangerous Baby Arizmendi was loaded with

thrills, controversy and sub-plots, which cannot be done justice within the

confines of a general feature. Then there were victories over the sterling likes

of Frankie Klick, Benny Bass, Chalky Wright, the clever Ernie Roderick, Pedro

Montanez, Ceferino Garcia, Lew Jenkins, Tippy Larkin, Beau Jack, Sammy Angott,

Willie Joyce and the Brownsville Bum with the killer left hook, Al (Bummy)

Davis.

Armstrong’s ring

style was all his own, even though it is easy at first sight to group him with

other famous fighters of a similarly relentless attack. Henry bobbed, weaved,

ducked, rolled, jinked and fired a constant hail of punches from all angles, but

always in his uniquely herky-jerky way. One writer described Armstrong’s

perpetual motion as a ‘quiver’. When the referee broke the action, Henry would

jig and jog straight back into the fray like a tenacious little pre-programmed

robot. It was a style that won him many colourful nicknames, but perhaps

Homicide Hank was the favourite of most. It sounded so much meaner than Homicide

Henry or other imaginative inventions.

Describe a

fighter as a ‘whirlwind’ and many get the impression of a man who flails away at

random and hits the target by the law of averages. Armstrong’s style was often

frenetic and he could certainly miss the target. But Henry was a canny and

educated puncher and expert at hunting an opponent and cutting him off. Henry

could jab, hook, cross and throw uppercuts with damaging speed and force. He was

also deceptively adept at slipping punches, as was Roberto Duran. Fighting the

peak Armstrong could crush a man’s spirit and will, because Henry was simply

unstoppable. The little dynamo just kept boring in all night long, seemingly

impervious to return fire.

He was a

punishing puncher who said of his third and final fight with Fritzie Zivic, “I

made him bleed inside. I hit him to the body, oh, how I hit him.” Armstrong was

on the slide when he delivered that merciless beating to Zivic in their

non-title confrontation at the Civic Auditorium in San Francisco in 1942.

Henry’s equation for success was blissfully simple in his own mind: “I hit you

in the middle, your chin comes down. I hit you in the chin, you go down.”

Extraordinary

Sportswriter

Rollan Melton met up with Armstrong in 1958, when the long retired Henry was

still in pretty good shape. Here is what Melton wrote: “Henry Armstrong, for the

benefit of the young generation, was a fighter of extraordinary talent and

action. He campaigned in the 1930s (and early 40s), when some folks stood in

line for bread and salt pork or told a guy at the bar entrance, ‘Joe sent me’.

As far as many of the young generation’s elders are concerned, Henry was just

about the finest thing that happened since Prohibition.

“Today’s steady

TV diet looks like love-making. Today, if a writer is among the more gentle set,

he writes, ‘It was a scientific bout’. Invariably the winner, be he a bum or no,

will immediately call for ‘a shot at the champ’.

“Armstrong

wasn’t a vocal champ. He just fought – all comers. He won three world titles –

featherweight, lightweight and welterweight – from October 1937 to August 1938

and held all simultaneously. No other fighter has accomplished the same.”

Born Henry

Melody Jackson Jnr. on December 12, 1912, America was teeming with hungry

fighters when Armstrong left high school and decided he would join the great

fistic gold rush. The year was 1929, America was reeling from the Wall Street

crash and Henry recalled, “It was jumping-out-of-the-window season. I was a $15

a week railroader. One day I picked up a wind-blown Global-Democrat newspaper

and saw where Kid Chocolate got $30,000 for a half hour’s work against Al

Singer. That did it. I quit on the spot. It was boxing from then on.”

Accompanied by

friends Eddie Foster and Harry Armstrong, Henry began his ring career as Melody

Jackson and travelled all over the country looking for fights, starting in

Pittsburgh, moving on to Chicago and then out to Los Angeles.

Chicago didn’t

hold fond memories for the future triple-weight champion. The drinking water

gave Henry a bad stomach and then he was rebuffed by a famous manager.

Armstrong’s pal Eddie Foster tried to talk Jack (The Deacon) Hurley into taking

a look at Henry, but Hurley replied, “Take the kid back home, send him back to

school.” The rejection of Armstrong was one of the few mistakes of The Deacon’s

illustrious career.

In California,

Henry ditched the name of Melody Jackson and Henry Armstrong was officially

born. His progress through the ranks in the years to follow would prove to be

every bit as fast and sensational as his non-stop style of fighting.

In 1936, singer

Al Jolson and actor George Raft bought Armstrong’s contract for $10,000

(believed to be the most accurate of the many sums quoted), just as the days of

milk and honey were approaching. Henry was shrewdly steered by his worldly

manager, Eddie Mead, whose salty friends and associates included the likes of

Bugsy Siegel, Frankie Carbo and siren Ruby Keeler.

Homicide Hank

didn’t disappoint anyone. There was no such thing as a boring Armstrong fight.

His fists would keep pumping relentlessly and many of his shots would stray

south of the border or conveniently jam thumb-first into an opponent’s eye. It

was a tough old game in Henry’s era and every seasoned pro knew all the tricks

and committed similar offences. Fritzie Zivic’s hyperactive thumbs would give

Henry permanent cataract problems in his right eye.

Petey Sarron: October 29, 1937

It was somehow

fitting that Henry Armstrong’s three world championships were all won in

boxing’s one-time capital city of New York. It was the perfect stage for gods

and greatness. In the humble opinion of this writer, it still is. Henry was the

4 to 1 underdog against Petey Sarron before a crowd of 12,000 at Madison Square

Garden, but the feeling among those in the know was that Sarron, fast pushing

thirty-one, was ready to be taken after campaigning busily abroad in England and

South Africa.

One punch was

enough to win the fight for Homicide Hank in the sixth round, when Sarron’s legs

caved in under the force of the payoff blow and sent him to the floor for the

first time in his career. Struggling on his hands and knees, Petey appeared to

lose track of referee Arthur Donovan’s count in the great roar of the crowd.

Sarron argued later on that he could have continued fighting, but his uncertain

movements on rising betrayed him. Dazed and unsteady, he had to be assisted by

Donovan.

The two fighters

were involved in a tremendous exchange when Armstrong pulled the trigger and

uncorked the overhand right that unhinged Sarron and finished his evening. Petey

had fared well through the first three rounds of the scheduled 15-rounder. An

awkward and unconventional fighter, described by one reporter as having “… an

eccentric, pin-wheel style”, he fired in punches from strange angles that

knocked Henry off balance and seemed to have him puzzled.

But ringsiders

noticed the snarl on Armstrong’s face and more significantly the menacing glint

in his eye. While Sarron’s volume of punches was making life difficult for

Henry, the quality blows were coming from the relentless little challenger.

Armstrong opened the third round by doubling the right hand to body and head and

clearly hurting Sarron. Henry would lose the round on a foul, but the sufferance

of penalty points for stray blows had already become meat and drink to him. That

second right to the head sent Petey careering into the ropes and drained him of

his speed and evasiveness.

Armstrong was

now in the ascendancy and Sarron could only enjoy his brief moments of success

and delay the killer wave that would swamp him. It was a game show of resilience

from Petey, especially after being lashed with a right to the head and a

debilitating left to the body in the fifth round.

Sarron continued

to spit defiance in the fateful sixth round. The balding little champ from

Alabama always had a look of fragility about him and now he began to look

frighteningly vulnerable. Armstrong trapped him on the ropes and larruped him

for a good minute before Petey fired back. His revival did not last for much

longer. Henry’s constant pressure was forcing Sarron to make mistakes, and Petey

committed the cardinal error in the frantic exchange of punches that preceded

the knockout. He dropped his left hand and Armstrong finished him in a flash

with the booming coup de grace.

Barney Ross At The Long Island Bowl: May 31, 1938

Barney Ross was

a fabulous fighter and the proud owner of a spectacular career. The gifted, New

York-born Chicagoan was the reigning world welterweight champion who had also

worn the junior-welterweight and lightweight belts. He had lost just three of

his 80 fights and had never been knocked out. Somehow he wasn’t knocked out or

even knocked down against Armstrong. But what a dreadful shellacking Ross

received. He never fought again after those fifteen hellish rounds against

Homicide Hank.

To this day,

when we see the film of that brutal encounter, we marvel in equal measures at

the ferocity of Armstrong and the fighting courage of Ross; a form of extreme

courage that today’s referees probably wouldn’t permit.

It is said that

Henry took to the scales for the Ross fight with lead in his boots. Many

onlookers might have been forgiven for thinking it was Henry’s gloves that were

loaded. Armstrong was jumping straight from featherweight to welterweight for

this audacious challenge, which presented him with a problem in the run-up to

the fight. A naturally small man, he had to puff himself up from 126lbs and get

as near to 147 as he could. At his training camp at Pompton Lakes, he began to

drink copious amounts of beer, which, in turn, would galvanise his appetite. So

went the theory, which a great many journalists have tested through the

centuries for no practical purpose.

The pounds piled

on, but Armstrong was still short of the mark on the day of the fight. He had to

weigh in at noon, and at nine o’clock in the morning he and trainer Eddie Mead

asked their doctor, Alexander Schiff, for advice. The solution was simple,

albeit intense: a steak breakfast with plenty of potatoes, followed by the binge

drinking of water.

Henry was nearly

floating at the weigh-in, where he claimed he hit the scales at 139 1/2 lbs (he

was a reported 133 1/2 for the fight). Even Eddie Mead couldn’t believe it,

while Commissioner Phalen was aghast. Phalen asked Armstrong if he had weights

under his feet or if Eddie Mead was perhaps performing some crafty magic with a

magnet. Both men laughingly dismissed foul play. The room was cleared, Henry was

weighed in private and the result was still the same. It was a good thing that

Commissioner Phalen didn’t stick a pin in Armstrong to see what would happen.

Phalen would have likely been drowned.

In a serious

vein, Armstrong’s weight-making ability, much like that of Archie Moore, was a

constant source of fascination. Drastic measures never seemed to affect Henry’s

performance, and he produced a real lulu against Ross. It was a wonder that

Barney was able to stay upright through the torrid 45 minutes of action. Twice

his handlers pleaded with him to let them stop the fight. Even hardened referee

Arthur Donovan wanted to halt the one-way traffic.

Barney would

have none of it. At the end of it all, the big crowd at the Long Island Bowl was

almost silent when the inevitable decision was announced. Ross was hugely liked,

to the point of being almost a saint in many people’s eyes. Much like a kindly

priest, he was not supposed to get so viciously mugged.

Before the storm

broke and the leather rained down, Ross battled Henry on even terms. For six

rounds, the fight was competitive and exciting. Then Armstrong began to move and

punch in earnest, scaling those giddy heights that few others could reach.

Outweighed by more than nine pounds, he seemed immeasurably bigger and more

powerful than Barney as the one-sided contest rumbled on. It is a constantly

intriguing mirage of boxing that a beaten fighter shrinks in physical stature by

the minute.

The beating

began in the seventh round, even though Barney won that session after a point

deduction from Henry for a low punch. Ross was all at sea thereafter, a man cut

off from his sunny little island and tossed into a violent maelstrom. His right

eye was banged shut for the last eight rounds, representing just a percentage of

the facial damage he inherited from Armstrong’s whirring fists. At the finish,

the right side of Barney’s face was horribly swollen, the left side covered in

welts and his nose and mouth were leaking blood.

It was a minor

miracle to most how he had managed to navigate his way through the last three

rounds, for in the twelfth he seemed to be on the verge of total collapse. His

knees sagged and his body bent fully over after Armstrong had battered him with

a volley of rights to the head.

In the

fourteenth round, Ross was spun around by a big left hook and the air turned to

a red mist from the spray of his blood. Henry closed in on Barney, weaving,

hooking and slamming away for the knockout, but the fighting instincts of Ross

again prevailed as he tucked up and blocked many of the follow-up blows.

Determined to

close the fight out like a champion, Barney somehow found the reserves to rally

back at Henry in the fifteenth and final round. But while Armstrong was finally

tiring, there was no steam in the fading champion’s punches. Henry, once again,

had proved himself a master of short-range punching. He missed his share of

blows, but the majority that hit the target were withering in their force and

accuracy. Barney couldn’t box Henry and he couldn’t fight him. There were not

too many men who could.

Lou Ambers: August 17, 1938

It was a split

decision win for Henry Armstrong over Lou Ambers at Madison Square Garden. Henry

had made history. The magnificent little titan was the simultaneous holder of

three world championships. But he had needed to summon up all his phenomenal

energy and determination to dethrone the fiery Ambers in a bloody and

spectacular fight for Lou’s lightweight belt.

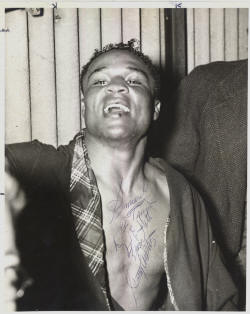

Such was the

intensity of Henry’s effort, he finished the fight with leaden arms and close to

exhaustion. He looked terrible in his dressing room, with cut and bruised eyes

and a damaged lip that required stitches. It was some time before he could haul

himself off the rubbing table and walk to the shower.

Armstrong lost

three rounds for low blows and then had to contend with a mighty rally from

Ambers down the stretch. Henry benefited from a barnstorming start, in which he

compiled a significant points lead. Few writers disputed that he was a deserving

winner, even though Ambers survived near disaster to charge back and whittle

down Henry’s points advantage.

Lou was nearly

bowled out of the fight near the close of the fifth round, when he was saved by

the bell after being hammered to the canvas by an explosive right to the jaw.

Things scarcely improved for Ambers in the sixth, when he was cut down again for

a count of eight. Both knockdowns occurred as Lou was trying to escape from

close quarters, where Armstrong was in his element as he dug away with his

favoured combination of a left to the body and a right to the jaw.

But Ambers was a

tough and clever man, a great champion in his own right, who could tilt with the

best of them. The so-called Herkimer Hurricane from upstate New York never did

know how to blow out gently.

Henry kept

punching. He always did. Failure to finish an opponent after an early success

never dispirited Armstrong. He believed that if you chop at a tree for long

enough, it will eventually fall. In a ferocious eleventh round, he tossed

everything he had at Ambers, but Lou would not go and was still full of fight.

He fought back to take the next three rounds, two of them due to Armstrong’s

infractions. But then Lou faced another major onslaught in the fourteenth as

Henry raced for the wire. A right hand catapulted Ambers into the ropes, which

saved him from his third trip to the canvas.

In the fifteenth

and final frame, Armstrong butted and pounded Ambers into the ropes as blood ran

down Lou’s right leg from Henry’s cut mouth. The crowd of 18,240 was roaring as

a right to the jaw shook Ambers, but it was Lou who came on strong in the final

seconds as the two great warriors traded punches beyond the bell in the bedlam.

Ambers, once

again, had shown himself to be a remarkably durable and determined man with

excellent recuperative powers. But his brave resistance and spirited counter

offence were not enough to save his championship. Most people in the pro-Ambers

crowd booed the decision. They had been particularly swayed by Lou’s stirring

comeback from adversity, which had resulted in Armstrong walking groggily to the

wrong corner at the final bell. Lou said that he had suffered no damage from

Henry’s low blows, though manager Al Weill was sufficiently riled to complain to

referee Billy Kavanagh at the end of the tenth.

The Associated

Press awarded Armstrong a decisive victory.

Freaky!

Was Henry

Armstrong a physical freak for his amazing stamina? This little ‘dusky fellow’

sure was something! What with Jesse Owens and Joe Louis also running riot, there

seemed no end to the athletic capabilities of these sepia supermen. Did the rest

of us need to worry and retire to underground bunkers? Doctors and scientists of

various capabilities were asked to investigate.

Well, I can’t

say what else Homicide Hank might have had in his genes, but he did have the not

unique gift of a slow heartbeat. Vicente Saldivar, another superb featherweight

champion of later years, was similarly blessed.

In May 1939,

Henry travelled to England to defend his welterweight championship against Ernie

Roderick at the old Harringay Arena in London. It was a good chance for the

eggheads to probe this American destroyer of men.

Armstrong was

examined by various medics, including a doctor hired by the Daily Express, who

concluded: “Armstrong is a freak of a generation. He is so perfect a human

dynamo that he is scarcely a fair opponent for any normal man near his weight.

He must have an oversized heart, not to the point of pathological enlargement,

but above normal.

“His pulse beat

is fifty-nine, compared with the normal of seventy-two, which makes him capable

of astonishing endurance. This was the secret of the runner, Paavo Nurmi of

Finland. Both Nurmi and Armstrong should will their bodies as cadavers for

research workers to examine.”

Henry Armstrong

outpointed Ernie Roderick over fifteen rounds and went back home. He didn’t live

forever, dying at the age of seventy-five in 1988. What instructions he left for

his cadaver, your writer doesn’t know.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|