| WAIL!. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL |

May-June 2000

|

|

SPIRITUAL ADVISER ON ALL MATTERS FISTIC: Hank Kaplan FOUNDER/PUBLISHER: Michael DeLisa EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Stephen Gordon ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Thomas Gerbasi WEBMASTER AND NEWS EDITOR: Ed Vance HISTORY & RESEARCH: Hank Kaplan, Tracy Callis, Matt Tegen, Harry Otty, Kevin Smith, Dan Cuoco, Larry Roberts STAFF WRITERS: Chris Bushnell, DscribeDC, Francis Walker, Dave Iamele, Katherine Dunn, John Vena, Rick Farris CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Enrique Encinosa, Randy Gordon, Pedro Fernandez, Joe Koizumi, Mike Moscone, Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, Jim Trunzo, Barry Lindenman, Pete Ehrmann, Monte Cox, Matt Boyd, Alan Taylor, Arne Steinberg, Lee Michaels, Joe Bruno, Lucius Shepard, BoxngRules, Adrian Cusack, Phrank Da Slugger, Pusboil. . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . |

|

Mr. Lindenman returns with something truly unexpected. A boxing

interview with, "The Red Rocker", Sammy Hagar, former lead singer for Van Halen.

I have to admit to being surprised when I read it. I had no idea that Sammy was so

into boxing. This is not a casual fan. Mr. Hagar knows his stuff & is a hard

EDITORIAL

RINSING OFF THE MOUTH PIECE

In the nether-noir that is the cesspool essence of the sweet

science, it ain't often that a cynical mo' fo' like The Ol' Spit Bucket, gets to

feel freakin' loopy about any of the Grassy Knoll-like machinations of the

powers that be in boxing ...

Let's jez say the "manly art", has been involved in some snarky,

dire, circumstances, as it crept, crawled, & slouched toward the 21st

Century. Truth be told, even The Bucket has questioned his motivation for being

a boxing evangelist more than twice.

Gotsta tell ya folks, within the sturm & drang of the myriad of

boxing expose's in the press lately .... Boxing's royal flush down the

toilet bowl of public opinion, crescendo'd on June 28 1997, when Leg-Iron Mike,

committed the, "Munch In The Crunch".

That was followed up 2 weeks later by the Lennox Lewis-Henry

Akinwande, Elmo Doll hug fest & yet another heavyweight championship DQ...

From there to the turn of the millennium, with extremely fleeting exceptions,

it's been a sad, seriously twisted tale, too sorry to recount ...

The day after that aforementioned, dark night, of June 28,

1997, The Bucket & his partner, Mike Delisa, came within a C-hair of

shutting the CBZ down.

Maybe we were a little over-amped, but we both believed that

Leg-Iron had betrayed the sport to the point where it was indefensible ... &

it wasn't until the Johnny Tapia - Danny Romero fight later in 97, that Mike 'n

me felt even a scintilla of interest & hope within the squared circle.

Mike, who founded the CBZ, was adamant about shutting it down - I

was also... But, there had already been 3 years of hard work by us & a

myriad of contributors who had all found a voice within the hopelessness that is

the modern state of boxing.

Many decades ago, way back in the early stages of the 20th Century,

all the outlaw sports that captured the fascination of America realized that they

had to get their shit together or they would not be able to maintain credibility as a 'sport" & continue to hold the public

confidence. The "Black Sox" scandal of 1920, was the wake up call.

Take the NFL ... George Halas & his cronies were just

guys out to make a buck & break a few bones promoting pay for play football, during the golden

age of college football. This decidedly unattractive sport, was called, Pro Football. Instead of being carny hucksters taking their unsavory sport &

teams from town to town in a totally disorganized fashion (sound familiar, boxing fans?), they formed a league, called it The National Football League,

established rules & bylaws & gave themselves at least a semblance of the

mantle of "respectability".

Since those halcyon, bygone days, every organized sport in America

has done the same - & Baseball, had already instituted this concept in the latter stages of the 19th Century ...

So Whhhaaaaatzzzz Uuupppppp wit' Boxing???

In these pukingly politically correct times, boxing is a true

anomaly ...Everything else in modern day Sports America is categorized, organized &

corporatized into a seamless vacuum of advertising tie-ins to generate revenue flow ad nauseum, into the gaping maws of greed that seemingly keep

the American Economy healthy these days ...

Yeah, well .... The Bucket, could go on & on down this grim

& hopeless road, but I will attempt to focus & meander on with this introduction to an outstanding issue of the CBZ Journal which by the way has

just been given a name.

From this issue forward the magazine name for the CBZ Journal will

be known as, WAIL!, The Cyber Boxing Zone Journal ...

Once again, I digress ... The point of this diatribe is that thangs

ain't been so good for boxing in the latter stages of the 90's ... But I been seein' glimmers of hope way off in the distance ...

& boy howdy was the Ol' Spit Bucket surprised earlier this month when

upon opening the USA Today sports section, I saw a feature on boxing. Not just a

feature, but USA Today has instituted monthly rankings for the 8 traditional

weight classes. Not only that, but we are also gonna get a State Of Boxing report every month!

The USA's new boxing columnist is Dan Rafael. I 've spoken

with him a few times recently & found him to be an engaging fellow, very enthusiastic

& knowledgeable about boxing. This is a guy who actually knows & has seen the

8th ranked flyweight from Thailand, whoever he may be.

Impressive & very cool that they have chosen a guy that is so

into the sport. It's also impressive that a national, mainstream, publication like The

USA Today would make such a commitment to boxing.

For five years The CBZ has published the excellent rankings that

are put out by internet boxing maven, Phrank Da' Slugger. From now on we are also

going to include Mr. Rafael's rankings along with Phrank's. Naturally, there are differences in their rankings but since both of them are so impeccably

researched we will be presenting both sets from now on on our new Rankings page.

In an upcoming issue of Wail! we will have an interview with Mr.

Rafael, that I'm sure will prove to be of great interest.

Which brings me to the current issue. This one's massive folks.

There are just too many great articles to introduce them all but there are four that I

must comment on: First off we have two, new contributors, Adam Pollock & Dan

Cuoco. I'm very pleased to debut two terrific new writers like these! These guys are real good & I hope we get to read them for many issues to come.

We also have the return of two of my favorite writers Pete Ehrmann

& Barry Lindenman. Pete is a legendary boxing historian, whose meticulous research

has graced the pages of The Ring Magazine, since the 1960's. He returns with an interesting article about "Red"

Herring.

core boxing guy.

I'm really pleased that Barry brought us this fascinating

interview. So much so, that we will lead of the new ish with it.

We are also printing a very

interesting piece by Aram "Rocky" Alkazoff, the winner of our Sonny

Liston contest. Suffice to say, this article needed a disclaimer.

Enjoy!

Bucket

INTERVIEW

with SAMMY HAGAR:

METAL

MEETS LEATHER

By

Barry Lindenman

Who would have thought? One of rock and

roll’s biggest superstars is also one of boxing’s biggest fans. Affectionately

known by his fans as “The Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar’s boxing roots date back to

the days when his father was a professional fighter. Fighting under the assumed

name of Bobby Burns, his father Robert Hagar was a respectable fighter back in

the‘30’s and 40’s. Early on, Sammy thought about following in his father’s

footsteps until the early 1960’s when groups like the Beatles and the Rolling

Stones turned him in the direction that would eventually make him famous around

the world.

Who would have thought? One of rock and

roll’s biggest superstars is also one of boxing’s biggest fans. Affectionately

known by his fans as “The Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar’s boxing roots date back to

the days when his father was a professional fighter. Fighting under the assumed

name of Bobby Burns, his father Robert Hagar was a respectable fighter back in

the‘30’s and 40’s. Early on, Sammy thought about following in his father’s

footsteps until the early 1960’s when groups like the Beatles and the Rolling

Stones turned him in the direction that would eventually make him famous around

the world.

After paying

his dues in the rock world much like a club fighter first pays his dues, Sammy

Hagar first gained fame and fortune in the early 1970’s with the band Montrose.

After tensions within the group forced him to leave Montrose, Sammy launched a

successful solo career in the mid 1970’s. Classic hits such as “I Can’t Drive

55” and “Three Lock Box” proved to the world that whether in a band or as a

solo artist, Sammy Hagar was a force to be reckoned with in the world of rock

and roll.

Despite being a success on his own,

Sammy Hagar’s music career took an unexpected turn in 1985 when he became the

front man for the legendary group Van Halen, replacing the departed David Lee

Roth. Sammy’s career with the band lasted twelve years, along the way producing

such hits as “Best of Both Worlds,” “When It’s Love,” “Runaround,” and “Right

Now.”

Sammy’s departure from Van Halen in 1996 also prompted the beginning of another career for

“The Red Rocker,” that

of entrepreneur. Sammy became the owner of the Cabo Wabo cantina in Mexico and

soon after began marketing his own brand of tequila. Unlike most rock stars whose

careers are destroyed by alcohol, Sammy Hagar’s career seemed to be fueled by

it.

“The Red Rocker,” that

of entrepreneur. Sammy became the owner of the Cabo Wabo cantina in Mexico and

soon after began marketing his own brand of tequila. Unlike most rock stars whose

careers are destroyed by alcohol, Sammy Hagar’s career seemed to be fueled by

it. In 1999, Sammy bridged his love of

tequila and his love of music with the release of the song “Mas Tequila.” The

song became an instant hit and once again reestablished Sammy Hagar as a

successful solo artist in the world of rock and roll.

Throughout his life, Sammy Hagar

followed boxing as closely as his managers were following the music charts,

befriending many of the world’s best fighters along the way.

Despite his extensive touring schedule,

he often attends championship fights live and never misses a chance to view a

fight on television. One need only hear him talk about the sport to realize

that the same passion Sammy Hagar displays on stage as a rock icon, he also has

for the sport of boxing.

BL: I

know your father boxed, as a featherweight I believe. Is that how you first got

interested in the sport of boxing?

SH: Absolutely.

My father actually fought as a bantamweight, a featherweight and a lightweight.

He fought Manuel Ortiz seven times. He fought him five or six times as an

amateur and then I think a couple of times as a pro. My dad’s first eight

professional fights as a bantamweight were knockouts. The guy could really

punch. That was his trip but it ultimately ruined him as a fighter because when

he realized he could just walk in there, hit somebody and knock them out,

that’s all he tried to do. He got himself nearly beat to death. I think my dad

had potential to be probably be a great fighter but after a while, he would

fight anyone. It became a money thing for him. He had us kids and he had to

make a living. So he’d take a fight for a couple hundred bucks and fight a guy

that weighed 160 pounds. He didn’t care. My dad would pack his bags and get on

a bus with my uncle and go down to the border towns in California and fight

Mexicans for any amount of money, any size guy, on a minute’s notice. Later on,

he tried to make me a fighter.

BL: If

you yourself were a professional boxer, is there any particular fighter whose

style you would you try and imitate?

SH: Let’s see, one who

doesn’t get hit a lot! I fought more like a Black fighter. I was more like a

Sugar Ray Leonard type fighter. I was not a big puncher. My dad was a puncher

and he trained me so when you’re a kid, the first thing you learn when you’re

fighting a grown man is how to jab and move. My dad was so slow compared to me

that I learned to become a very fast jabber. That’s the style that I was

heading towards because I had brother who was three years older than me who was

also into boxing, and I had my father. Those were the guys who I always put on

the gloves with every day. Therefore, I learned to be fast.

BL: What’s your opinion about the current

popularity of women’s boxing?

SH: There’s

some pretty good fighters out there now. We all know about Christy Martin. She

does a damn good job but to be honest with you, I’m not big on women’s boxing.

It just kills me to see a woman get hit in the tits. It’s like a man getting

hit in the balls! They’re in there and they take all those punches. It can’t be

good for them. It’s just not flattering to see a woman get cut and spitting

crap out of her nose. At the same time though, I have a different opinion about

a woman than I do a man. I like to see a man get the shit beat out of him!

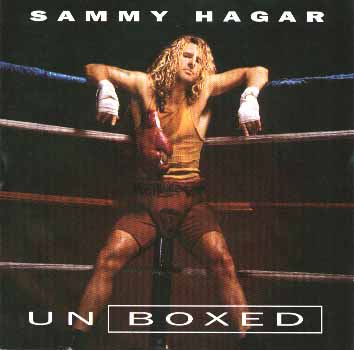

BL: Much of your

music contains direct references to boxing. For example, your pictured on the

cover of your greatest hits box set, “Unboxed,” in a boxing ring wearing trunks

with gloves around your shoulders. And at the end of your song “Mas Tequila,”

you say the phrase “no mas, no mas” which is what Roberto Duran said to the

referee when he quit against Sugar Ray Leonard. Are these boxing references

conscious efforts on your part are they just coincidence?

SH: Even

though boxing has always been such a big part of my life, they’re really just

coincidences. To this day, I’ll drop everything to watch a good fight. I own

Direct TV, only for boxing matches. You can ask my wife. I can watch any other

sport imaginable now, but I’m just looking for boxing all the time. Boxing has

always been part of my world. That photo of me in the ring was for a Rolling

Stone photo session in New York. I suggested Gleason’s Gym so the next thing I

knew I was dressed up in boxing gear. They used it in their book of greatest

“Rolling Stone” magazine covers and I decided to use it for the cover of my

“Unboxed” CD. The “no mas, no mas” thing just stands for anything no when

you’ve had enough. But when I use it, it’s about drinking shot after shot after

shot of tequila! That was a classic line though to use in a fight.

BL: A few years

ago, you recorded the song “Winner Takes it All” for the soundtrack of Sylvester

Stallone’s movie “Over the Top.” Did you ever get the chance to meet him and

talk boxing?

SH: Oh

yeah. We spent something like fourteen hours making that video. That was the

first

SH: Oh

yeah. We spent something like fourteen hours making that video. That was the

first

BL: If

you were part of a celebrity boxing match, what celebrity would you want to get

in the ring with and smack around for a few rounds?

SH: That’s

good. Let me really think about that for a second. There’s some people that bug

me even worse than some guys that I’ve been in bands with. It would have to be

Eddie (Van Halen).

BL: That

would be a one round fight for you though. That’s a cakewalk for you.

SH: Well

aren’t those the ones you want? Like I said, you want to be fast and not get

hit. That’s the name of the game.

BL: How did

your relationship with Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini first come about?

SH: I

was always a fan of Ray. I’ve always loved those kinds of fighters like Ray and

Arturo Gatti who get in the ring and are ready to die in there. Guys like that

have always been my favorite kinds of fighters to watch. In Ray’s case, I think

he became more famous for losing a fight probably than any fighter in history,

the way he lost to Arguello. People saw his heart and soul in that fight and everybody

fell in love with him, including me. My manager at the time, Ed Leffler, met

Ray at a restaurant in Los Angeles and told him that I was a big fan of his. It

turns out Ray was a big fan of mine as well. So we hooked up on the telephone

soon after and from that day on, I knew he was my kind of guy. Ray has become a

great friend of mine. He came to my wedding. He’s been to house many, many

times. He comes to my concerts whenever I play in LA. Because he’s such a great

human being, I really think the tragedy of the Duk Koo Kim fight affected him

tremendously. He’s one of the most sensitive, sweetest people on the planet. I

think that was devastating to him and he never really got over that.

BL: Any

plans to help out your good friend Oscar De La Hoya as he tries his hand at a

music career?

SH: Oscar

jammed with me at the Cabo Wabo (the cantina Sammy owns in Mexico). He came up

to sing with me on “I Can’t Drive 55.” It was so cool.

BL: Can he

sing?

SH: Yeah.

He was screaming. He wasn’t really trying to sing. But the guy’s handsome and

the girls love him. Why not try it? As long as it doesn’t interfere with his

boxing career, I would say more power to him. It’s really great to be able to

do other things. That’s the great thing about success. It allows you the

opportunity to at least try and do other things. He’s such a big star,

especially in the Latino community. God bless him. If he makes a great record,

I’d play on it. The main thing though is that Oscar is a great, great fighter

and he shouldn’t lose that desire that he has to fight. Walking out on a stage

is an easy gig compared to walking into the ring. If that starts to get good to

him and he loses his boxing drive and fire, that would be a real shame because

he’s one of the great fighters of all time.

BL: Besides Ray and Oscar, who are some other fighters that

you’re friends with?

SH:

Carlos Palomino is a gentleman and a really great guy. Ruben Castillo has

always been a buddy of mine. I met Jerry Quarry a couple of times. We sat and

watched some fights together at Ruben’s house. This was before he had his real

problems. I can remember being at Ruben’s house with Ray Mancini, Ruben, Jerry

and Mando Ramos watching Tyson and Razor Ruddock with the Jeff Fenech – Azumah

Nelson fight on the undercard. It was a pretty strong room that night. I don’t

know many heavyweights. Most of my fighter friends are in the smaller weight

divisions. I’ve always found boxers to be the nicest, most gentle people that

you’d ever meet.

BL: Who’s your favorite fighter of all time?

SH: I

think Sugar Ray Robinson was just one of the greatest ever. Muhammad Ali as

well. They were both such innovators of the sport. They brought new things to

the sport. They could stand right in front of you and not get it. That’s just

such an art. And now you got Roy Jones. At first, I liked Roy Jones. Then there

was a period when I disliked him. Then when he knocked out Virgil Hill with one

punch to the body. My God, it was like, wait a minute, this guy really is

great. It’s just such a unique style of fighting. It’s sort of what Pernell

Whitaker started. I think Whitaker was a great, great fighter. That guy could

stand right in front of you, and you couldn’t hit him. Those are the kind of

guys you want to see get beat all the time but you got to hand it to them. I

think Sugar Ray Robinson was the first of those kind of fighters. It’s tough to

find a better fighter than him.

BL: What’s

your favorite boxing movie of all time?

SH: Without

a doubt, “Raging Bull.” DeNiro was so unbelievable. He played my father in that

movie. That was my dad right there. Beating the shit out of his brother,

beating the shit out of his wife, hotheaded, accusing everybody of everything,

doing all the wrong shit. I got Goosebumps watching that movie. It’s one of my

favorite movies of all time.

BL: Of the

young fighters out there, is there anybody out there whose ability and style

you think can restore some credibility back to the sport?

SH: De

La Hoya certainly has the ability. I think Trinidad certainly has it as well. A

fight like the Morales – Barrera fight is all we need every once in a while. It

isn’t just the fighters that we need, it has to be the fight itself. We have to

see good fights. Look at De La Hoya. He fought Whitaker and Trinidad and now

he’s fighting Shane Mosley. He’s not ducking anyone. I think he’s doing a great

job for the sport. You can be the greatest fighter in the world but if you

don’t fight the right people, you’re worthless. I think Lennox Lewis has so

much potential but if he had Mike Tyson’s aggression along with his size and

skill, he would be invincible. He doesn’t have any gumption. He’s like me. He

doesn’t want to get hit.

BL: Powerful,

motivating type music (like the theme from “Rocky” and Survivor’s “Eye of the

Tiger”) often accompanies a boxer’s gym workout. What songs of yours do you

think would be good selections for a fighter to listen to in the gym?

SH: I

think a song that I wrote with Van Halen called “Get Up” on the “5150” album

has a lot of good boxing lyrics in it. Another song that I wrote with Van Halen

called “Dreams” really motivates you mentally to really make it happen and go

for it. If you’re listening to songs like these, you are not gonna quit.

They’ll drive you. It’s like having a good trainer.

BL: Knowing

the demands and potential rewards and pitfalls of both, would you prefer your

teenage son to become a rock star or a professional boxer?

SH: Certainly a rock star. In some respects, they’re very

similar. The careers are short lived. If you make it, there’s huge money and

unbelievable opportunities for about five years. They’re both a lot of hard

work though. People think that rock stars are people that do nothing for a

living. It’s the writing and the recording process that really takes up every

second of your time. It’s a lot like training for a fight. The performance is

like the fight. You stay focused for your two and ½ hours on stage. But when

you’re writing or recording, you have to be in dreamland. You can’t have any

distractions and you have to just let those ideas come.

BL: If you

were a professional boxer, do you think you would you call yourself Sammy “The

Red Rocky” Hagar or would you have something else in mind?

SH: I’m sure I’d be called “The Red Rocky.” It just kind of fits.

BL: Are any

other of your pals in the rock world also big boxing fans like yourself?

SH: A guy who’s not necessarily my pal because I’ve never met

him but I know that Billy Joel is a big boxing fan. Like myself, I think he

used to box too. My old drummer from my days with Montrose, Denny Carmassi, is

a huge fan. We’ve been to more fights together than any two human beings on the

planet. Denny is definitely a boxing fanatic.

BL: You recently had your hair cut off on "The Tonight Show" for the organization "Locks of Love", which makes hairpieces for those children who have lost their hair from disease and medical treatment. What do you think it would take for Don King to make a similar donation?

SH: That mop of his! I don’t think anybody would want that on

their head. I’d rather be bald.

A Modest Proposal for the Preservation and Improvement of Pugilism,

with Specific Emphasis on a General Response to the Fallacies of the Purported

Reformers of the Sport

by Ancora Imparo

Friends, have you ever seen a lousy fight? Lousy, that is, in any of the conventional ways -- match-up, performance, or result. If you have watched more than two fights you are certain to have seen one, so you need not feel unique. The effect on the viewer of a lousy fight, as we have defined it, frequently has one of two affects upon the viewer; it stirs the desire to (1) ban and abolish or (2) : (a) to overhaul and improve.

When a thing ceases to be an object of controversy, it ceases to be an object of interest.-- William Hazlitt, "The Spirit of Controversy (Jan. 31, 1830) Cleombrotus ceased to be a pugilist, but afterwards married and now has at home . . .a pugnacious old woman hitting as hard as in the Olympian fights, and he dreads his own house more than he ever dreaded the ring.

-- Gaius Lucilius, Epigrams, circa 131 B.C.

Reluctantly, I shall not seek in this discourse to address the former, although I reserve the option of rebuttal should the need arise to defend the uninterrupted participation in the sport by those who choose to do so. Number two intrigues me (scatological reference noted but ignored.)

How, then, may we "overhaul and improve" boxing without draining from it the noble and the beautiful? Before answering this important interrogative, we must move from the general to the particular, and muster a list of universal complaints. In short, what is it about modern boxing that has caused lawman and conman alike to explore ways of changing a sport that has remained essentially unchanged since the days of the Trojan wars?

One scientific survey has isolated boxing's chief ills: Lack of uniform rules, Alphabet organizations, corrupt promoters, sycophantic journalism, elderly round-card girls, and Max Kellerman. All of the varied and innumerable "solutions" are aimed at one or more of these issues.

Perhaps the most frequently cited "problem" with boxing is the lack of uniform rules. The reality is that boxing rules differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction in only the most inconsequential of ways. Perhaps in one state a "standing 8-count" is allowed while another does not. Another venue may allow a ringside doctor to stop a fight while yet another empowers the referee only. Quibbles, as in fact the basics remain the same. In boxing, there are not major differences between jurisdictions -- there are no different Leagues -- one using a designated hitter another not. Indeed, I have never heard a fan complain --"Gee, I wish we were using Nevada's rules here in New York." So, no, despite what you hear, the lack of uniform rules is not a major factor.

Another problem cited by nearly all the pundits is the proliferation of "Alphabet Organizations." Each organization names his own champion, the multitude of title-holders, world and regional, cheapens the meaning of the word champion, and confuses all but the most diligent fan. And most are run by foreigners. The fans themselves are somewhat to blame for this however, as the promoters and networks soon learned that even a concocted title belt translates to increased attendance, viewership, and geetch. Promoters who ignore "titles" and put on good solid club fights without regard to the "alphabets" simply do not survive. Fighters, fans, and haberdashers love belts as tokens of victory. Looking more closely at the history of the sport, in fact, one must realize that during Regency Boximania each battle had at stake the opponent's "colors," and the winner would leave the ring with a visible token for victory. (The difference there was that no weight divisions existed and the only title was that of Champion of England). One might suggest, then, that one solution to boxing's problems would be to make every fight a championship fight of one sort or another; alternatively, we could eliminate all weight divisions and anoint the "Champion" based on pound-for-pound skills. These potential solutions, valid, though facile, shall be set aside for now.

A global view reveals that the dissatisfaction derived from the remaining problems can be distilled into one abused word: justice. Or, to be more exact, the perceived lack of fairness at the various levels of the sport -- fighters are unfairly ranked and fighters are unfairly awarded verdicts of the promoter-influenced judges.

The majority of complaints that cross over from the small pond of boxing journalism to the larger cesspool of modern day sports in America arise when from out of these waters rises a stench fouler than putrefied fish -- the odor exuded by the bad decision. Every decade has its shouts of "robbery" that bring forth the reformers, who deluge the press and public alike with suggestions of open scoring, public scoring, neutral judges, solvent judges, judging clinics, ad nauseum. To wit I respond -- "Punch and get out!"

We must recognize here and now that no two persons view a fight the same way. The record books are littered not only with those lousy verdicts recalled today, but hundreds more that no one recalls or cares about -- one example, of multitudes shall suffice: Ken Overlin losing to Billy Soose. Irrelevant, well, you are right. The history quickly obliterates all but a tiny fraction, preserved in great part by reprinted articles in Ring.

This observation leads us to the modest proposal referred to in our title. A proposal so simple that it is sure to be adopted to the joy of villagers throughout the land: Revert to No-Decision bouts.

I'll repeat that again, slowly: Revert to No-Decision bouts. No decisions have a long historical predicate in the sport. For many years, right through the 1930s, they were commonplace. No Champion lost his title on a bad decision in those days as the kayo was the sole arbiter. Respected journalists of the day rendered their opinion as to the winner, and each fan had his choice of a plethora of newspapers and verdicts. everyone was happy. So, Panama Joe Gans could cuff Jeff Smith mercilessly for 8 rounds and be declared the loser in one paper while the winner in another. Genius I say!

Recently a group of boxing writers made a splash by announcing that they were taking on the arduous task of compiling "valid rankings" for the sport. I call upon these same writers to support our proposal. They already voice there opinions on the fights -- it will be easier to implement no decision bouts than to vote on miniflyweights from the Philippines.

Hence, the sport will be saved. Luckily there are a plethora of well-informed journalists in the sport, with more added every day. Indeed with the web, every fan can be a journalist, so everyone can decide his own winner. As Bones McCoy said of a scheduled brain transplant --"It is so simple even a child could do it!!"

To recapitulate, the salvation of the sport mandates the following ---

Spread the word -- salvation is at hand. You can thank me with some hot chicken soup. Finis.

- Every fight shall be for a championship

- Each fan-journalist decides who wins, except for knockouts

- Journalists decide who rates for a title fight (except those that the eat free food in the pressroom)

- Youthful Round Card Girls Wear Thongs

Joey

Giardello: “I Thought I Could Beat Anybody” For the record,

in 1950 alone, Giardello fought 16 times. ‘Nuff

said.

Joey Giardello,

born as Carmine Tilelli on July 16, 1930, in Brooklyn, NY, was a fighter’s

fighter. With no amateur

background, Giardello, whose father was an amateur fighter, began his boxing

education in the pro ranks in 1948. He

scored a second round KO over Johnny Noel in Trenton, NJ, and a career spanning

19 years and 133 bouts began.

Giardello was

by no means a power puncher, and he was mainly known as a no-nonsense cutie in

the ring. He could make you look

bad, and while he could be flashy, he was a blue-collar worker who gained the

respect of his peers quickly.

One would think

that a fighter with little power would want to stray away from the heavy hitters

of the day, but not Giardello. “I

thought I could beat anybody. I feared no one,” said Joey.

“A slick guy would give me more trouble.

The punchers didn’t bother me. They

were slow.”

By 1951,

Giardello had compiled a 35-4-2 record, and was ready to take on top 10

contender Ernie Durando. Joey took a 10 round decision, and the boxing world began to

take notice.

Giardello’s

record in his next 12 bouts though, was a spotty 6-3-3.

This led top contender Billy Graham to deem Giardello a safe bet.

Joey was no such thing, as he took a ten round decision from Graham in

Brooklyn in August of 1952. A

rematch was held in New York four months later, and Giardello won a split

decision…until the New York State Athletic Commission stepped in.

Two NYSAC members illegally changed one of the judges’ scorecards, and

Graham was given the victory. But

Giardello didn’t sit idly by. He

sued and took his case to the New York Supreme Court, which once again gave

Giardello his rightful victory.

A third match

was fought with Graham in March of 1953, and Billy took a 12 round decision.

Giardello was a legitimate contender now, but he would not receive a

title shot for another 7 years, despite scoring victories over Gil Turner,

Walter Cartier, Tiger Jones, Rory Calhoun, Chico Vejar, Spider Webb, Holly Mims,

and Dick Tiger, with whom he split a pair of fights in 1959.

The win over

Tiger, in November of 1959, earned Giardello his overdue title shot, against

Gene Fullmer in Bozeman, Montana, for the NBA Middleweight title (April 20,

1960). As Giardello remembers, “I

thought I beat him. All the

newspapers said I beat him, but in his hometown, he got a draw.” The Fullmer

fight was a war, punctuated by dirty tactics from both men.

“He was buttin’ me and buttin’ me, and finally I got underneath him

and I came up with my head and busted his face.

We’re friends now though,” Laughed Joey.

The draw had an

effect on Joey, as he told author Peter Heller in the book, “In This

Corner”: “I thought that was it, though.

I didn’t think I would get another chance, because I didn’t have the

same heart into the fighting game.”

Giardello

continued to fight though, and after putting together a 9-5-1 record over the

next three years, he was matched with the legendary Sugar Ray Robinson, with the

winner to receive a shot at champion Dick Tiger’s title.

Suddenly, Giardello had his fire back.

“Mr. Ray Robinson was a great fighter, don’t get me wrong, but he

would not fight me,” remembers Joey. “Then

he wanted to fight Dick Tiger for the title, and Tiger said he would fight the

winner of Robinson and Giardello for the title.

So I beat him. In those days

it was hard to beat me. It’s all

according to how you train, and if I would have trained right, no one would have

beat me. I just wasn’t the best

training fighter.”

The win over

Robinson, in June of 1963, earned Giardello a December, 1963 shot at the world

championship. That night, December

7, was the high point of Joey Giardello’s career.

“Oh, that was it,” exclaimed Joey.

“I went all those years, 15 years, before I got the chance for the

world title. Robinson wouldn’t give it to me.

And Dick Tiger did.” Giardello

told Heller in “In This Corner”: “I was determined. If I was fighting a heavyweight, I could have beat him that

night…The only thing I remember is he couldn’t hit me…I knew this was it,

I’m thirty three years old, this was it.

I knew the postman don’t ring twice now.

I trained good.”

After losing

his championship to Tiger, Joey Giardello fought four more times, losing two,

with his final win coming over Jack Rodgers in Philadelphia on November 6, 1967.

Joey Giardello

retired with a record of 100-25-7, with 1 no-decision.

32 of his wins came by way of knockout.

He was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993.

“I want to be

remembered as a tough fighter who took no baloney from anybody” said Giardello.

“I wouldn’t want anybody to wreck my career, by saying bad things

about me to my children. I want

them to know who their father was.”

To the sons

of Joey Giardello, your Dad is a true champion. ADAM'S ANALYSIS By Adam Pollack SELLOUT

MOE AND HIS JEWISH HEAVYWEIGHT BY

ENRIQUE ENCINOSA

He

was the stuff that boxing lore is made of. They

called him "Sellout Moe" and he was a chunky old man with twinkling

eyes and a mischievous smile on his wrinkled face. In his youth he was a four

round fighter, a topnotch trainer and corner, manager of world champions and

contenders, but above all, Moe Fleischer was the king of matchmakers. There

was a time long ago, before television and computers, even before frozen

dinners and Hitler, when boxing flourished in America. In New York City it was

common to have a dozen pro cards in a single week, sometimes four or five

running on the same night in different neighborhoods of the Big Apple. Across

the river, in New Jersey, pro cards ran weekly in Newark, Jersey City and other

urban centers. The competition for fighters was fierce among promoters. To draw

crowds a boxing card needed to build up local heroes, often in tough fights,

and match together a show that would motivate the public to buy tickets even in

lean times. It

was the age of Moe Fleischer. At one time he was matchmaking eight cards a week

in three different cities. One of his fight clubs was so successful that it

experienced twenty-three consecutive sellouts, earning Moe his famous nickname. "I

liked that nickname," he once told me, "It sounds a lot better than

other boxing nicknames like "Fainting Phil" or "The Bayonne

Bleeder." I had a good nickname. The newspapers made it up…" Before

he became "Sellout Moe" he was just another kid from a poor Jewish

neighborhood in Manhattan. He worked in the mailroom of a New York newspaper

and would often run errands for a boxing writer better known for his expertise

with a gun, the legendary Bat Masterson. As a youth Moe dreamed of following

the path of Joe Benjamin, a neighbor who fought Terrible Terry McGovern, but

reality sank in after being trounced in his first two fights. Studying

to become a trainer, he worked corners almost daily. Although he was often

younger than the pugs he cornered, Moe showed such hustle that a top manager

named Slick Paddy Mullins offered him a chance to train a young prospect named

Sammy Cohen. Moe turned Cohen into a flyweight contender who traded leather

with Pancho Villa and Frankie Genaro. Moe

Fleischer, barely out his teens, earned his living training topnotch fighters

of the era, including the popular Jimmy Slavin, welterweight contender Sergeant

Sammy Baker and lightweight headliner Bruce Flowers. The greatest break in his

career came the same week Moe was wed. An offer was made for Fleischer to train

heavyweight Tom Heeney. "The Hard Rock from Down Under" was scheduled

to fight Gene Tunney. Unwilling to postpone his wedding or give up the chance

to work a heavyweight title fight Fleischer did both. He married, took Heeney

to the wedding reception and left on his honeymoon dragging his heavyweight

along. "We

would get up at five in the morning to do roadwork," Moe related years

later, "My wife was not very happy with the strange arrangement but she

had no choice. This was my job and I was committed to it, to a chance of a

lifetime." Heeney

did not beat Tunney but Moe established a friendship at that fight with a Cuban

fight manager named Pincho Gutierrez. The Cuban journalist turned boxing

entrepreneur hired Moe to work as trainer and booking agent for his squad of

young fighters. The two best were Black Bill and Kid Chocolate. Black Bill was a Cuban flyweight named Eladio Valdez, who borrowed his ring

name from an earlier Black Bill, a heavyweight who had fought Sam Langford. The

little flyweight was a lightning quick combination puncher, a veteran of

several years of pro fighting in Havana rings, often against bigger opponents. "Black

Bill was one good fighter," Moe said in one of our interviews, "He

could box, hit, fight inside or outside and he was slick, hard to hit. He had a

lot of talent and he was in the top ten ratings for five years. I took him to

Canada and he beat every one of those little guys over there. He fought in New

York and won and lost with Corporal Izzy Schwartz and fought a thriller with

Willie Davis. The trouble with Bill was his training methods. He was a hard

worker at the gym but a harder worker with a woman, a bottle or a nightclub.

People talk about Kid Chocolate and his partying…I tell you Bill was worse. He

would get into street fights with bigger guys and get arrested. Bill drank,

smoked, gambled and chased every skirt he could find, even though he had a wife

that was twice his size…she weighed over two hundred pounds." Black

Bill, also called the Cuban Ink Spot, fought Midget Wolgast for the flyweight

crown in a New York ring, circa 1930, losing a tight decision. "By

the time Bill fought Wolgast." Moe said sadly "he was washed up. Bill

had suffered venereal diseases and was going blind and he hid it from me. When

Pincho and I found out we retired him, but it was a tragic ending. He had not

saved a nickel and was too troublesome to hold down a steady job. He drank

more, tried to kill his wife and then shot himself with a gun in a New York

boarding house. That was in thirty-four. Bill was a great little fighter but he

was a wild boy." "Chocolate

wasn’t easy either," Moe said, "he was a great champion but he threw

his money away in expensive suits, loose women and sleek cars…but he was some

fighter. I think he was the greatest fighter I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen them

all. He could do everything and I saw him make some moves I’ve never seen other

fighters make. He was so fast, that he would hit you three times with the same

jab before you realized he had thrown the first one…Once we were fighting up in

Pennsylvania and I left the dressing room for a few minutes. When I returned, I

smelled gas. Someone wanted the local boy to win badly and they could have killed

Chocolate with that open gas line. By fight time the Kid was woozy and I wanted

to cancel the fight but the Kid insisted he could beat the local boy even

drugged up. I beat him Moe-he said-I beat him. I was worried but Chocolate won

every round. It was all instinct. He was a natural, the best fighter I’ve ever

seen. If he had not whored around he would have been champion for ten

years." Kid

Chocolate had a career record of 132-10-6 with 50 KO wins. Sellout Moe worked

with Chocolate in more than eighty of those bouts. My

favorite Sellout Moe anecdote took place in the bleak days of the Great

Depression. "Times

were tough," Moe said in an old interview "but a man could get by on

twenty dollars a month. I paid seven dollars rent for a nice apartment in New

York. I was making ends meet but I was busy matchmaking in New York and Jersey

and shipping fighters to other states. One day I get a call from a promoter in

Connecticut. He tells me he has a local fighter who’s drawing good crowds and

he has a Jewish convention in town and he needs a Jewish heavyweight for a

sell-out. The purse is fifty bucks, which means a lot in those days. I could

live for a month on my share of that fight, so I tell him I have a Jewish boy

named Abie Cohen and we make the deal." Moe

had no Jewish fighter but he did have an Irish veteran named Hynes who was

willing to wear a Star-of-David in his trunks in order to feed his family. On

the train ride over to Connecticut, Moe darkened Hynes graying locks by

applying a burnt cork to the club-fighter’s scalp. Hynes

was nervous by fight time. His opponent was a well-muscled, large, black

heavyweight. At the time of his introduction as Abie Cohen, the Irish boy did

something out of reflex that he had done in seventy-five previous fights: he crossed

himself in a typical Catholic gesture. "The

Jews in the audience gasped," Moe related, "but I told the promoter-

Abie is of mixed blood. His mother is Catholic and his father is Jewish." Hynes

hit the local boy a few good body shots and was repaid with a booming right

hand that decked him at the end of the round. Abie Cohen returned to his corner

on wobbly legs." "I

had paid a kid to work the corner with me," Moe said, "and he started

sponging water on Hynes head. To my horror, the black soot from the burnt cork

started running down his face. It was Abie Cohen’s last fight. Hynes got

stopped in the second and we were fined twenty bucks but with the thirty left

over we had enough to pay the bills for a few weeks." Moe

continued to work in the fight game, earning his nickname based on twenty-three

straight club sellouts. "Like

all matchmakers I had to give the local hero an edge," he said of his

matching techniques, "but not too much of an edge. I made competitive

fights." Moe

slowed down during the fifties, not liking the characters that controlled the

fight game. When his wife died in the sixties, Sellout Moe wanted to die also.

He was despondent but was rescued back into the boxing trade by the Dundee

brothers. "They

saved my life," Moe said to this writer, "Chris said –Come on down to

Miami Beach, Moe. Angelo has lots of fighters and we need someone we can trust

to work with the promotions. This gave me a chance at life…I’ve known Chris

since we were boys. Chris managed Midget Wolgast and we worked opposite corners

when I had Black Bill…and Angelo I’ve known since he was a kid hanging out in

the gym learning the trade from Ray Arcel." For

over two decades Moe worked at the Fifth Street Gym, where he worked with young

fighters and old journeymen. His glory days were not over, for Moe took on a

young prospect from the Bahamas named Elisha Obed, molding the raw talent into

a world champion. "Obed

was a good fighter," Moe recalled, "He had a long reach, a solid

right hand and good reflexes. I traveled all over the world with him, to Paris,

to Brazil and Germany. He was the first world champion from the Bahamas and

they treated me royally every time I visited Nassau. It was fun." Even

living legends pass on. Moe died before the beloved Fifth Street Gym was torn

down. His wake was held at a funeral home in Little Havana, a fitting place for

a last curtain, for Moe had been an important part of Cuban boxing lore. Ferdie

Pacheco, Angelo and Chris, Frankie Otero and Hank Kaplan were there, as was Joe

Robbie, the sports entrepreneur. It

was Moe Fleischer’s last sellout room. Enrique

Encinosa can be reached at encinosa@hotmail.com Jose

Napoles By

Rick Farris A

few months later I got a little longer look at the future welterweight king when

I saw him flatten Ireland's Des Rea in five rounds on the undercard of a featherweight

main event featuring Dwight Hawkins and Frankie Crawford at the Forum. Pernell Whitaker Vs. Gods, Monsters, and Superheroes Diary

of a Young Heavyweight – First of a Series Clifford

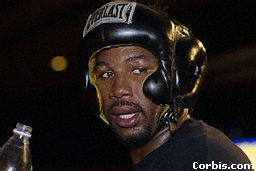

“The Black Rhino” Etienne As

told to Thomas Gerbasi

Clifford

“The Black Rhino” Etienne is a 30 year old heavyweight prospect.

Etienne is currently 16-0 with 11 knockouts.

His most recent victory was a unanimous 10 round decision over highly

regarded Lamon Brewster on the debut of HBO’s KO Nation Series. Etienne

was a standout student and athlete in high school.

His prowess on the football field earned him recruiting interest from

Oklahoma, LSU, and Texas A&M. “I

was born in Lafayette, Louisiana, but I grew up in New Iberia.

My Mom and Dad kept a tight rein on me.

We stayed in the neighborhood, outside the city limits, in the country.

I was really a loner most of the time.

When I started coming up in school, and playing ball, I got really

popular. It

was something I wasn’t used to.

I just tried everything, and when they started letting the reins loose a

little bit, I made some bad choices.”

Etienne

spent 10 years in prison, where he learned to fight at the age of 18.

“I

was 18. I

liked boxing. I

used to watch it, and I’d never miss it on TV.

No matter what, people are going to try you sooner or later.

You’re going to get in a lot of conflicts.

That’s human nature, especially when you’ve got a lot of men together

in one spot. I

handled myself like a real man the whole time through.

I respected everybody, and I was respected back, even from the wardens

and correction officers.

I didn’t have too many problems. “I

feel that because of the time I spent in prison I was preserved.

I haven’t been in any wars and took beatings.

I feel like I’m 23, 24.

My body is in good shape.

I’m not in a rush.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s patience.” Etienne

turned pro in 1998 under the auspices of agent Eddie Sapir and Promoter Leslie

Bonano. Don Turner soon joined J.C.

Davis as trainers of Etienne.

“Being a

fighter, you want to fight the good guys. You

want to make good first impressions. Even

if you’re not ready sometimes. My trainers feel like I’m ready to step up. I

know I’ve got over 100 years of experience in my corner.

It’s another confidence booster. But

I’m not short on confidence by a long shot.

I train hard, I work hard, I eat right, I live right. So I know that any time I get up in that ring, my opponent

had better have done the same thing himself.

I’m serious. When I get in

there, I’m like, I’ll take my time, do this, do that. But when I get in there and someone might catch me with a

punch or something, BAM! I just

kick it up a notch. It’s a war in

there. Etienne’s

work rate surprised observers, and made “The Black Rhino” a fighter to watch

in the heavyweight division. “They’re

gonna see a fight. They’re not going to watch heavyweights hugging and

holding. Because

my opponent’s going to have to fight when he gets in there with me.

Either he’ll fight or check out of the ring.

I throw a lot of punches for a heavyweight.

I work out like that, and I can fight like that.

I guess that’s why people are shying away from me.” Etienne

soon learned that a young and talented heavyweight does not find too many people

willing to fight him. Was it

frustrating?

“In

a way it is because I’m looking to step up, and I look forward to challenges,

but I take it as a compliment.

I’m a humble guy.

I do a lot of hard work, and I know that the only way I’ll get

something out of this is if I put something in.

So I put in a lot.

I love the game, man (laughs).

You’ve got to love it.

I get up in the morning, put my miles in, run hard.

After a fight, I don’t even stay home.

I just got married, and I was back in training camp a couple of days

later." Fellow

unbeaten Lamon Brewster stepped up to the plate in May of 2000, one of the few

ready to take on the Rhino. “He’s

a young guy, and he’s got skills. I’m

gonna put the pressure on him. He’s

never been knocked out, and I’m gonna see what I can do.

I’m gonna see if I can knock him out.

"I’m

making a statement every time I get in the ring.

I’m making statements to all heavyweights, not just the one I’m gonna

beat up in there…all of them. Come

in the ring, this is what you’re going to expect.

No less. "This

is my life. I’m at camp more than

I’m at home. I know that if I

sacrifice now, I’ll see the benefits in the future. I’m paying my dues.

I’m studying my craft, I watch films, I try to learn from the older

fighters, everything. My goal is to be heavyweight champion of the world.” CHARACTER MAKES CHAMPIONS Scott LeDoux: Part Two By Eric Jorgensen After he retired, Scott joined the Minnesota State

Athletic Commission and also served a brief stint as a referee with Verne

Gagne's American Wrestling Association (becoming an instant fan-favorite).

He retired from the AWA when his first wife passed away from cancer in 1983. And,

that’s not all. He possessed a quick and stunning overhand right, which he

could deliver “on time”, along with a walloping uppercut. These

talents along with his steady movement, outstanding reach, and superior

reflexes made him a great fighter. Odd (1989 p 60) wrote that he had a “killer

punch in each hand.” Jay Bright, former trainer of Mike Tyson, said, “Holmes

was the consummate boxer, very slick, very cagey, with a terrific jab and a

nice right hand. He used every ounce of the ability he had” (see The Ring,

November 1996, p 29). His

greatest weakness was a vulnerability to an inside attack, against which he was

always on guard. According to Larry, “I always fought better moving away than

coming forward” (Holmes 1998 p 99), beating his man to the punch and then

getting away. His anticipation of his opponent’s moves on offense and defense

was uncanny – “when I was on top of my game, I swear I had a sixth sense that

enabled me to see things before they happened” (Holmes 1998 p 112). A

member of a large family brought up in poverty by a mother alone, he helped it

survive Holmes

was an outspoken man who always said what was on his mind. Never as fancy with

his words as his idol, Muhammad Ali, he was sometimes misunderstood - but

always honest. Larry once said “I’m a businessman first and a boxer second”

(Myler 1998 p 156). In the ring, he was all business and his record speaks for

itself. Incidentally, he was an excellent businessman outside the ring too. Larry,

along with Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali, dominated the heavyweight division as

never before. He was called the “most dominant heavyweight king since Joe

Louis” and it was written that his “chief weapon was his sterling jab” (see The

Ring, November 1996, pp 28-29). He

was an outstanding amateur fighter and began his professional career in 1973,

winning 48 straight fights before losing his first contest in 1985. Mee (1997 p

158) called the loss a “controversial points decision.” He defended the title

21 times and gave credibility to the IBF Heavyweight title when he accepted it.

Perhaps,

his greatest effort came in 1978 when he defeated Ken Norton to capture the WBC

Heavyweight Championship. In a “nip-and-tuck” bout and one of the greatest

fights ever, Larry edged Ken in a disputed split-decision. In this bout, he showed the true grit of

which he is made - a great fighter of the mold “when the going gets tough, the

tough get going.” According to the man himself, “This was the best fight I was

ever in” (Holmes 1998 p 112). In

an article in The Ring (November 1996 pp 28-29), Dave Anderson, sports

columnist Holmes,

along with George Foreman, Jersey Joe Walcott, and Bob Fitzsimmons, proved that

“old men” could fight successfully as heavyweights. All four of these talented

fighters fought well into their forties and “whomped” many young studs that

other top boxers did not want to fight. Dangerous well past his prime, he tangled

with the very best men available – including Ray Mercer, Evander

Holyfield, Oliver McCall – and held his own. At the age of forty-seven, he

fought Brian Nielsen for the IBO Heavyweight Championship and pounded the huge

Dane before losing a split decision. He actively campaigned for a match with

old George Foreman but it never came to pass. For most of his career, Larry lived in the

shadow of Muhammad Ali. As a sparring

partner for the Champ, the young Holmes knew he could give Ali a hell of a

fight and began to think he could beat him (Holmes 1998 p 62). In 1980, he met and defeated the great one

in the ring and hated every minute of it. He battered his former mentor and had

him at his mercy before the contest was stopped. According to Holmes, “Ali was

my idol, a tremendous fighter, but he stepped out of his time into my time”

(Bunce 1998 p 168). Bert

Sugar (1980 p 21) wrote “A younger, tougher, and better Larry Holmes ‘whupped’

him in every which way … Ali knew it was all over after the first round.” Many

fans believe that Larry - with his height, reach, and power - may well have

been a match for the “real” Ali in his prime. Myler

(1998 p 156) wrote “Despite living in the shadow of Ali throughout most of his

championship reign, Holmes earned grudging admiration from many fans as a fine

champion.” Bunce

(1998 p 190) wrote, “As the years pass Holmes’ status as a modern great

increases. He fought on a regular basis and met all of the contenders and

pretenders from a period when most of the heavyweights wasted their talents.

Holmes is the best heavyweight from the tarnished years between the last of

Ali’s sweet jabs and the vicious hooks of Tyson. If time had been kinder to

Holmes it is possible that he would be held in even higher esteem.” Once

at a press conference, Larry made a “Marciano slur” in which he demeaned the

skills of the unbeaten slugger. He has since called Marciano a “great champion”

and said he didn’t mean to impugn the “Blockbuster” as a man but only wanted to

emphasize that he felt he could have beaten Rocky (Holmes 1998 pp 236-237). Owning a 48-0 record at the time, he lost

his next two fights and fell short of matching the 49-0 mark of the “Rock.” The

two losses were to Michael Spinks and, this writer, feeling that Larry was

better than Michael, has always seen these losses as questionable verdicts. Sugar

(1980 p 23) wrote of Holmes, “A man who invests boxing with a dignity it

sometimes doesn’t deserve, he deserves better than he has received. This man

can do it all.” Larry has stated, “Against all odds, I succeeded” (Holmes 1998

p 279). Herb

Goldman, former Editor of The Ring Record Book and the International Boxing

Digest (IBD) monthly boxing magazine, ranked Holmes as the #3 All-Time

Heavyweight (The Ring, 1987 p 1071). The Ring (1999, p 126) ranked Larry

as the #5 All-Time Heavyweight. In the opinion of this writer, Holmes was the

#10 All-Time Heavyweight (and perhaps deserves an even higher ranking). Bunce,

S. 1998. Boxing Greats. Philadelphia: Courage Books Holmes,

L. 1998. Against the Odds. New York: St. Martin’s Press Mee,

B. 1997. Boxing: Heroes & Champions. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books,

Inc. Mullan,

H. 1990. The Great Book of Boxing. New York: Crescent Books Myler,

P. 1998. A Century of Boxing Greats. New York: Robson/Parkwest

Publications Odd,

G. 1989. The Encyclopedia of Boxing. Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell Books, Inc. Sugar,

B. 1980. Holmes-Ali:The Last Hurrah (contained in The Ring, December

1980, pp 20-23). New York: The Ring Publishing Corp. The

Ring. 1987. The Ring Record Book and Boxing Encyclopedia. New York: The

Ring Publishing Corp. The Ring. 1996. Battle of the Legends

(contained in The Ring, November 1996, pp 28-29). Fort Washington, Pa:

London Publishing Co.

The Ring. 1999. The 1999 Boxing Almanac

and Book of Facts. Fort Washington, Pa: London Publishing Co.

By Thomas

Gerbasi

From

1998 to the present, middleweight champions Bernard Hopkins, Keith Holmes, and

William Joppy fought a combined 16 times. Having

said that, it’s little wonder that the former Carmine Tilelli laughs when

asked about the state of the sport today. “Aw,

it’s terrible,” said Tilelli, who is best known as former world middleweight

champion Joey Giardello. “ 12 fights and having a title fight? Jeez, I had a hundred and something before I got one.

When they made so many champions, I stopped watching boxing.

Every fight was a championship fight.”

From

1998 to the present, middleweight champions Bernard Hopkins, Keith Holmes, and

William Joppy fought a combined 16 times. Having

said that, it’s little wonder that the former Carmine Tilelli laughs when

asked about the state of the sport today. “Aw,

it’s terrible,” said Tilelli, who is best known as former world middleweight

champion Joey Giardello. “ 12 fights and having a title fight? Jeez, I had a hundred and something before I got one.

When they made so many champions, I stopped watching boxing.

Every fight was a championship fight.”

Giardello

held the middleweight crown for two years, before losing it to Tiger in a

rematch in October of 1965. As champion he won two non-title ten rounders over Rocky

Rivero, and defended the crown with a clearcut 15 round decision over a hard

punching challenger, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

The unanimous decision over Carter did not invoke any controversy until

35 years later, when a movie chronicling the life of Carter hit the Silver

Screen. In the movie, Carter is

shown walloping Giardello, only to be robbed of a win by a racist decision.

This obviously didn’t sit well with anyone who saw the fight,

especially Joey Giardello. “I was

the type of fighter who liked to win for my family, and for something like that

to happen, it hurt. I was very

discouraged about it.” A

defamation lawsuit was later filed by Giardello, who said of the Carter bout,

“He was just another guy. I had

boxed for almost 20 years, and I had fought Ray Robinson and every tough fighter

out there. It was just a regular

fight.”

Giardello

held the middleweight crown for two years, before losing it to Tiger in a

rematch in October of 1965. As champion he won two non-title ten rounders over Rocky

Rivero, and defended the crown with a clearcut 15 round decision over a hard

punching challenger, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

The unanimous decision over Carter did not invoke any controversy until

35 years later, when a movie chronicling the life of Carter hit the Silver

Screen. In the movie, Carter is

shown walloping Giardello, only to be robbed of a win by a racist decision.

This obviously didn’t sit well with anyone who saw the fight,

especially Joey Giardello. “I was

the type of fighter who liked to win for my family, and for something like that

to happen, it hurt. I was very

discouraged about it.” A

defamation lawsuit was later filed by Giardello, who said of the Carter bout,

“He was just another guy. I had

boxed for almost 20 years, and I had fought Ray Robinson and every tough fighter

out there. It was just a regular

fight.”

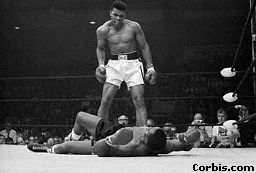

THE STORY WAS WALCOTT Ever since the May 25, 1965 first

round knockout of Sonny Liston by Muhammad Ali in their heavyweight championship

rematch, debate has focused on whether Liston threw the fight. Regardless

of whether he intended to throw the fight, the focus should not be on Liston as

much as it should be on Jersey Joe Walcott, former heavyweight champion and referee

for the fight.

Ever since the May 25, 1965 first

round knockout of Sonny Liston by Muhammad Ali in their heavyweight championship

rematch, debate has focused on whether Liston threw the fight. Regardless

of whether he intended to throw the fight, the focus should not be on Liston as

much as it should be on Jersey Joe Walcott, former heavyweight champion and referee

for the fight.

It is clear that Sonny Liston was struck by a quick right hand from Muhammad

Ali and fell to the canvas. The punch that dropped Liston was so quick

that many did not see it and called it a phantom punch, speculating that Liston

went down without being hit at all. Slow motion film of the bout revealed

that Ali's rapid fire right landed on the left side of Liston's jaw as Liston

came forward with a left jab. Liston's head can be observed jolting from

the punch.

Despite the fact that the punch landed, many question whether the punch had

enough force to drop Liston. Force equals velocity multiplied by mass.

Clearly Ali's punch was extremely fast. However, many felt the element of

mass was missing, that Ali's body was not behind the punch. A careful viewing

of the fight film, especially from a rare side view shown on the ABC

rebroadcast, indicates that more of Ali's body was behind the punch than was

apparent from the frontal view. Rocky Marciano commented that the punch

appeared to begin as an arm punch, but at the end of the punch, Ali does appear

to put his body behind it. What is of most importance is not how much mass is

behind the punch at its beginning, but at the point of impact.

However, Ali was never known as a great puncher. In Muhammad Ali's entire

boxing career, his only first round knockout was against Liston. Ali went the

distance with men like Joe Frazier and Ken Norton. George Foreman stopped

each in two rounds. Foreman has said that Liston never

backed up from him in sparring. "I was afraid of him. You

didn't want to be in there too long with him." If Foreman couldn't

back Liston up, how could Ali stop him? It seemed odd that Liston, who

had never been knocked down previously, who was considered to be amongst the

strongest

heavyweights, should be dropped by one Ali punch.

Some noted that Liston was observed with and had probably worked for members of

the mob. It was suggested that they might have bribed Liston.

Perhaps Liston simply had no heart. What was lacking internally to

motivate him to rise from the stool after the sixth round in the first fight

may have affected his mental ability to take a punch in the second fight.

The drive, desire, and confidence may have been absent.

Some noted that Liston was observed with and had probably worked for members of

the mob. It was suggested that they might have bribed Liston.

Perhaps Liston simply had no heart. What was lacking internally to

motivate him to rise from the stool after the sixth round in the first fight

may have affected his mental ability to take a punch in the second fight.

The drive, desire, and confidence may have been absent.

On the other hand, the Ali blow was quick, and there is a saying in boxing that

it is the punch you do not see that causes the most damage. Additionally,

Liston had moved forward with his own mass with his left jab. His own

body weight propelled into Ali's fist, increasing the impact of the blow.

As fighters age, they often do not take a punch as well. Some speculated

that although Liston was listed as thirty-one, he was probably closer to

forty. As his birthdate is unknown, so too is his age.

Lack of activity can also diminish a fighter's ability to take a punch. Other

than the six round beating Ali handed him on February 25, 1964, Liston had not

fought many rounds. He had stopped Floyd Patterson twice in the first

round, on September 25, 1962, and in the rematch on July 22, 1963, prior to his

loss to then Cassius Clay. Accordingly, Liston had fought only eight

rounds in approximately two and a half years. Liston was reportedly in good

condition prior to the bout, but then it was delayed as a result of an Ali injury.

Some believed that Liston lost his conditioning and sharpness following the

delay. Furthermore, if Liston had wanted to throw the fight, why would he

choose such a punch? He was hit with what appeared to be a more powerful

and solid right a bit earlier in the round. Surely he could have dropped

from that punch if he wanted to throw the fight.

There is no definitive proof that Liston took a dive. It is clear that Liston

was hit. It is also clear that Liston arose from the canvas. There is

nothing in boxing that says you cannot go down from a punch. After being

knocked down, Liston at first struggled to rise, and then finally did.

After returning to his feet, he and Ali resumed the bout. If Liston truly did

not want to continue, he could have remained flat on his back and pretended to

be knocked out. However, that is not what happened. Liston arose

and continued, just as many fighters do when they are knocked down. At

that point, Liston did what we would expect any champion to do. Regardless

of whether Liston went down legitimately, he arose and was prepared to

continue.

While it is unclear whether Liston legitimately went down, it is patently

obvious that Jersey Joe Walcott's actions as referee were improper.

Referee Jersey Joe Walcott did not stop the bout because Liston was unable or

refused to continue. Rather, the bout was stopped because Walcott decided

to stop the bout without providing Liston a count. Therefore, it was the

intervening actions of the referee which superseded any allegedly improper conduct

of Liston. It is these actions which should truly be focused upon.

Judging the actions of Joe Walcott require no speculation. However, in fairness

to Liston, Joe Walcott's history deserves as much scrutiny as has been provided

Sonny Liston. The Ali - Liston rematch was not Joe Walcott's first

involvement with a dubious first round knockout.

On September 23, 1952, Jersey Joe Walcott was well ahead on points and on his

way to successfully defending his heavyweight title against Rocky Marciano.

Although Marciano had landed big punches, Walcott had taken them well, and had

even become the first man to deck Marciano. However, the cumulative effect

of Marciano's blows had sufficiently softened Walcott for a Marciano

bomb. In the thirteenth round, Marciano landed a thunderous right cross

to Walcott's jaw, which knocked Joe out. Marciano had scored a comeback

victory.

On May 15, 1953, Marciano and Walcott fought the rematch. In this bout,

Walcott did not demonstrate his superior boxing skills in order to mount a

points lead as he had in the first bout, nor did he demonstrate the powerful

counterpunching which had floored Marciano. This time Walcott was hit by

a single right hand which dropped him in the very first round. Walcott

almost immediately sat up and looked at the referee giving him the count.

Walcott appeared clear headed, looking at the referee and observing the

count. As he had his legs outstretched, he needed to bring them underneath

him to rise from the canvas. However, Walcott did not attempt to rise until the

count of nine. By the time he arose, the referee had counted to

ten. Joe Walcott had been stopped in the first round.

Although it seems clear based on Walcott's demeanor that he could have risen

early in the count, begun to rise early in the count, or placed his legs

underneath him so he could rise quickly when he needed to, he did not take any

course of action other than to sit up and look at the referee counting over him

until "nine" was reached. At that point, it was too late to

begin the process of getting his legs under him and pushing off the canvas with

both his legs and fist.

Jersey Joe Walcott, the man who had given Marciano so much trouble one year

earlier and taken his blows for thirteen rounds, the man who had arguably

defeated Joe Louis in one bout and was ahead on points in a second prior

to being knocked out in the eleventh round, had been officially knocked out in

the first round. Previously, the earliest Walcott had been stopped was

six rounds, by Abe Simon back in 1940.

Immediately following being counted out, a clearly cogent Walcott protested in

vain. Following the bout, the forty year old Walcott announced his

retirement. The question to this day remains, 'Why didn't the

clear-headed Walcott even attempt to rise earlier?' From the visual images

alone, Walcott was more able to rise in 1953 than was Liston in 1965.

Although not a referee by trade, the inexperienced Jersey Joe Walcott was

appointed to referee the Ali-Liston rematch. When the fight was introduced

by the ring announcer, Walcott was conspicuously missing from the

picture. He was late entering the ring. This was an ironic harbinger

of things to come.

By rule, Ali was required to go to the neutral corner following a knockdown.

Following the Liston knockdown, Ali taunted Liston and began dancing about the

ring in delight. Ali failed to go to a neutral corner, and the

inexperienced Walcott was unable to send Ali to the neutral corner. At

first Ali circled the ring, hovering over Liston. Walcott attempted to catch up

with Ali. Finally, Walcott directed Ali to a neutral corner, who then

disregarded the direction, continuing to circle the ring with his hands

raised. Thus, at no point did Ali go to the neutral corner and remain

there until directed to approach ring center by the referee. Ali

completely disregarded the rules, and

Walcott never enforced them.

The neutral corner rule had been around for decades. The rule stated that

the ten count would be suspended until the fighter scoring the knockdown went

to the neutral corner. In the famous 1927 heavyweight championship

rematch between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney, Dempsey had knocked Tunney down,

but failed to go to the neutral corner as required by the new rule. It

was not until Dempsey properly went to the neutral corner that the referee

began counting over Tunney. Although Tunney arose at the count of nine,

he had been on the canvas for fourteen seconds. This lead many to debate

whether Tunney could have risen in time had the count begun before Dempsey went

to the neutral corner. Thus, the neutral corner rule had not only been a part

of boxing for over thirty-five years, but it was a famous rule as a result of

the Dempsey-Tunney bout.

Later modifications of the neutral corner rule provided that the count by the

ringside timekeeper would begin immediately, and the referee would pick up the

count from the timekeeper after directing the other boxer to the neutral

corner. In general, this occurs at about the count of four, but usually

no later than seven. At the very least, a fighter is provided three or

four oral counts by the referee so he can rise in time. If a fighter is

so recalcitrant as not to go to the neutral corner, then as a penalty for

failing to obey the rules, referees will not pick up the true count from the timekeeper,

but will suspend the count altogether, beginning it again only after the

fighter complies with his directions. Never will a referee penalize a

fallen fighter by not providing him a count at all as the result of the other

fighter failing to go to the neutral corner. Depriving the fallen fighter

the benefit of a count as a result of the actions of the scofflaw opponent would

provide a perverse incentive to fighters.

Failing to ensure Ali's presence in the neutral corner, Walcott either attempted

to pick up the count from the timekeeper or was distracted by Nat Fleischer,

editor of The Ring, who informed Walcott that Liston had been down for over ten

seconds. At that point, Liston had risen and engaged Ali again.

Following his discussions with Nat Fleischer and/or the ringside timekeeper,

Walcott finally turned around and again focused on the fighters. Walcott

stepped between the two combatants and terminated the bout. At no point

did Walcott provide Liston a count, as required by the rules. It is amazing

that Walcott was either unaware of the famous neutral corner rule or decided to

disregard it.

The purpose of a ten count by the referee is to provide a fighter the opportunity

to rise within ten seconds. By providing the fighter a count, the boxer

can know exactly when to rise in order to continue the bout. It is the

exclusive responsibility of the referee to provide the fallen fighter the

benefit of a count. A fighter cannot be counted out by the timekeeper or

a magazine editor. A fighter is never required to provide himself a count

and speculate as to when ten seconds have