Editorial: Rinsing Off The Mouthpiece

By GorDoom

Since the Sturm & Drang of the De La Hoya-Trinidad "fight" has finally subsided, the Ol' Spit Bucket thought he'd weigh in on the matter. First, after repeated viewings & discussing it with numerous boxing people with varied opinions, all of whom I respect; I still stand by my original conclusion:

De La Hoya by 8 rounds to 4.

With that out of the way, I thought it was a crap fight. The pre-fight hyperbole touting it as the 2nd coming of Leonard - Hearns I was ludicrous. Sugar Ray or the Hit Man would have run both of those guys right out of the ring ... I'm not saying Oscar or Tito are bums, far from it, as they are both skilled fighters. But compared to the aforementioned, they're Saturday Night Specials, going up against Cruise Missiles.

The "Fight Of The Millennium" was a huge snore. The expected pyrotechnics were a fizzle. Oscar stayed on his bicycle for 8 rounds & boxed beautifully, while Tito dutifully trudged after him in a straight line seemingly clueless about the concept of cutting off the ring.

Then Oscar ran out of gas. Or focus. Or will. He gave away the last four rounds & Tito took advantage of it. That doesn't mean he wiped the floor w/Oscar, he just won the last 4 rounds.

1999 is the year that all the long anticipated "super fights" finally came to fruition. Unfortunately, for one reason or another they have invariably been disappointments. Holyfield-Lewis, De La Hoya vs. Quartey & Trinidad all landed with a thud.

Of the three match-ups, Oscar & Ike put on the best show, but the reality is that there were 3 exciting rounds and 9 dull ones. In all three match ups the endings were inconclusive & controversial. The Holyfield/Lewis decision reeked so much, that even politicians caught enough of a whiff to smell opportunity for publicity & joined the circus ...

The Bucket ain't about to rehash old news, suffice it to say these fights were all like bad sex, none of them got me off ...

Now that I've kvetched about those fights, let me say that so far this year, the fight of the year, hands down, is Tapia-Ayala. That my friends was a fight ...

There are no fights on the books as this is being written (Oct. 15), that promise to be as good during the remainder of the year. Lewis-Holyfield II, Hamed-Soto, Morales-McCullough & Grant-Golota are the best bets. All of them are intriguing but I'm not holding my breath ...

*********

R.I.P. Wilt Chamberlain. There are certain figures in one's life that are immutable in your consciousness. Chamberlain, like Ali or Jim Brown seemingly have always been a part of my life. The Bucket has never been a B Ball fan, but the Big Dipper commanded respect. Wilt was a man's man & made no bones about it. He was the Babe Ruth or Wayne Gretzky of B Ball, but he was also, well into his 50's, a world class volley ball player & marathoner.

Chamberlain was a true Renaissance Man. A man of varied intellectual pursuits, he was writing a script when he died. He was also an astute businessman & highly opinionated raconteur. .

I'll miss his immense presence.

*********

Before I introduce the new issue there are a couple of web sites I'd like to turn y'all on to: Boxing historian, Monte Cox has an excellent historical site at http://coxscorner.tripod.com .

One of the highlights is the weekly all-time rankings by a panel of

experts that Monte has assembled. This week it's the middle weights & guess what? The

#1 all-time isn't Sugar Ray Robinson.

Check it out. It's a very informative boxing site.

The 2nd site I want to present belongs to the CBZ's own, Chris

Bushnell. Chris' site is http://www.boxingchronicle.com.

It's the CBZ's editorial staff's consensus that Chris is the best fight reviewer we've ever

read.

The Ol' Spit Bucket means it when he sez Mr. Bushnell has set the bar

very high for other reviewers to reach. On his site you will find every fight review that

Chris has written for the CBZ as well as other articles.

The CBZ has been very fortunate the last few months as an abundance of

terrific, new, writers have started contributing on a regular basis. Alan Taylor, Matt

Boyd, Rick Farris & JD Vena, are the most recent to saddle up.

This issue we present four more terrific boxing scribes. Three of them, Arne

Steinberg, Monte Cox & Eric Jorgensen are all erudite & diligent historians of the

fight game. We are lucky to have such experts in the field join our staff. All of them

have contributed remarkable articles this month.

Hell, the Bucket thinks all of these new contributors I've mentioned have

contributed some outstanding boxing articles, the kind you won't find anywhere else ...

Last but certainly not least, the fourth new guy at the table, thanks to Katherine

Dunn who introduced us; is the redoubtable Lucius Shepard.

Lucius is a Hugo & Nebula Award winning science fiction writer as well as

a screenwriter & journalist who has been published in Rolling Stone, Spin &

Playboy among others.

As Katherine Dunn puts it, Mr. Shepard is a "Fistic scholar of

high seriousness & wit". His first boxing experience was on December 3rd,

1960 when as an 11 year old he watched the controversial rubber match between Gene Fullmer

& Sugar Ray Robinson which ended in a draw. Even at that tender age, Lucius told

me, he was outraged at how Robinson was robbed.

Lucius' first contribution is an account of the tribulations of small time

boxers down in Yucatan, Mexico. His gritty account flashed me back to my own childhood in

Mexico in the 50's & something I hadn't thought of for about 30 years ...

Due to my father's job, the Ol' Spit Bucket live in Mexico from 1955 to '62.

Unlike in the U.S., boxing is a major sport, on a comparative par with the NBA, or NFL,

throughout Mexico & all of Latin America.

My father, a Depression Era pro fighter, started managing & training

fighters in Mexico as an avocation. By the time I was seven, Lil' Bucket was working

corners for my fathers fighters. What I did was carry the spit bucket, & pass sponges,

cut equipment, towels & rinse off the mouth piece, making sure to get it back to the

fighter before the next round started.

I have to say this gave me an up close & personal look at violence

& courage under extreme duress at an early age. It also developed a deep respect in me

for fighters & especially Mexican fighters.

Reading Mr. Shepard's article brought back one experience in particular. It

was 1960 & we had two fighters on a "card" in a small town near Lake

Tequesquitengo, in the mountains of Morelos, a couple of hours from Cuernavaca.

It was in a dusty pueblo that had a small bullring that held two,

three hundred people at most. Keep in mind, what I'm calling a "bullring" was

actually a huge corral surrounded by rickety wooden bleachers.

When we got there there was still a bullfight going on. We sat down to watch

with the maybe 100 or so people that were scattered around the bullring, along w/assorted

mongrels, chickens, pigs & donkeys that meandered around underneath the stands to grab

some shade from the remorseless heat & fight over whatever scraps of food that fell

thru the slats above..

The young matador (maybe 18 years old), was an obvious novice. When it came

time for the kill he was so nervous he couldn't finish off the bull who wasn't much more

than a yearling. He must have attempted the coup de grace at least a dozen times.

The bull was dripping gore from multiple stab wounds but he kept coming ... The

"crowd" got restless & mercilessly got on the young torero's case.

It was starting to get real ugly when finally a stout, balding, man (who

later turned out to be the town butcher) jumped into the ring, ran up to the combatants,

shoved the incompetent swordsman aside & grabbed the exhausted, bleeding, bull by one

of his horns & slammed a knife into the back of the bulls head.

The unfortunate animal slowly slid to it's knees & then toppled

over spewing blood all over the middle of the bullring.

The crowd went wild.

Then it was time for the fights. They dragged the carcass out. The center of

the bullring was a bloody mess ... A bunch of campesino's trudged in. One of them

dispiritedly swept some dirt over the crimson gore & viscera. The rest of them dug 4

holes in the ground & placed four large poles haphazardly in a rectangle. Then they

proceeded to tie some ropes around the poles & presto! We had the most ersatz fight

ring I've ever seen, featuring the bloodiest canvas possible.

I mention all this to illustrate that Lucius'

outstanding article about the primitive boxing conditions in Yucatan is no exaggeration.

S'anyways, that's about it for this month, except for one

last item: Ed Vance, our creative & stalwart webmaster & news editor has

come up w/two good, new ideas. Fan Forum & the CBZ Newsletter.

S'anyways, that's about it for this month, except for one

last item: Ed Vance, our creative & stalwart webmaster & news editor has

come up w/two good, new ideas. Fan Forum & the CBZ Newsletter.

Fan Forum gives our readers a chance to vent their feelings about the myriad

of boxing subjects that constantly evolve. So send your letters in and as long as they're

decipherable, Ed will post them in the Fan Forum section.

The other new wrinkle that Ed has come up with is the CBZ Newsletter. The

Newsletter which is e-mailed out a few times every week lets our readers know when new

items have been posted. Everything from boxing news to major fight reports to letting you

know when the new issue of the Journal is being posted.

I strongly recommend that our readers sign up (the link is on the main page),

so that they can keep abreast of the constantly shifting world of boxing ...

Enjoy the new issue!

GorDoom

The Flyweight

by Lucius Shepard

In southwestern Mexico there is a small town named Santander

Jimenez. During the early 70s it was a much smaller place than now, the most

insignificant of dots on the map, a farming community with a few blocks of potholed

streets and rundown stucco buildings, and a single motel--a one-story wooden structure

painted green, topped by a tarpaper roof, and divided into six units. At dusk groups

of campesinos could be seen walking into town, the men carrying rifles and

machetes, their wives trailing behind , holding babies, all heading for the cantina or the

movie theater or the plaza, where they would sit by the fountain in the accumulating dark

and talk and drink

In southwestern Mexico there is a small town named Santander

Jimenez. During the early 70s it was a much smaller place than now, the most

insignificant of dots on the map, a farming community with a few blocks of potholed

streets and rundown stucco buildings, and a single motel--a one-story wooden structure

painted green, topped by a tarpaper roof, and divided into six units. At dusk groups

of campesinos could be seen walking into town, the men carrying rifles and

machetes, their wives trailing behind , holding babies, all heading for the cantina or the

movie theater or the plaza, where they would sit by the fountain in the accumulating dark

and talk and drink

pulque or burro (unrefined rum) from bottles without labels. When

I went into the plaza to ask directions, I was greeted with hostility--it seemed that

long-haired gringos were not held in high esteem--and I retreated to my van thinking that

Santander Jimenez was a place where I wanted to spend as little time as possible. It

certainly was not the sort of place where I expected to see professional boxing, but on

checking into the hotel I saw a poster

stapled to the office door advertising a six-bout card to be held that same night in the

movie theater, featuring the light-heavyweight champion of Yucatan. I also

discovered that one of the rooms in the hotel was occupied by six fit-looking guys, some

of whom looked to be about my age (I was 22) and who were extremely solicitous of my

girlfriend. They told her they were a boxing team and had traveled all the way from

Merida to fight. They invited her and--as an afterthought, me--to attend.

The movie theater wasnąt much bigger than a theater in a multiplex. A ring had been set up in the center of the place and about a hundred folding chairs arranged around it. There werenąt any overhead lights; the only illumination came from the projection booth, so that as the boxers fought, huge indigo shadows of the combatants were cast onto the screen. The bouts were all decent quality club fights, ranging from flyweight to light-heavy, and the guys from Merida held their own, even though some of them were in against much heavier opponents. I was particularly impressed with the flyweight, a quick-handed boxer without much power, but with excellent movement and defensive skills that set him apart from the rest. As the card progressed I realized that the six guys were all wearing the same pair of white trunks--I recognized the bloodstains--and that they only had one pair of shoes among them. A smallish pair, apparently, as the two largest guys fought barefoot.

The light-heavyweight champion of Yucatan was a man in his

late twenties built along the lines of a Yaqui Lopez. His stance was too

straight-up, and he threw uppercuts from the outside, tendencies that would have gotten

him into trouble with world class opposition. But he was in with a teenager who

couldnąt have been more than a junior middleweight: a thick-waisted blond kid with

a ruddy complexion that grew considerably ruddier over the eight round distance. He

absorbed dozens of power shots, but except for a reddened face and an

increasingly stubborn expression, he showed no effects and kept moving forward, whacking

the champ with a wicked left hook to the body. By the middle rounds the champ had

lost much of his enthusiasm for the fray and he began to circle, snapping back the kidąs

head with a jab. But the kid kept on throwing the hook, walking through fire to

unload it, his shadowy image on the screen appearing much more violent and menacing than

he himself, and by the seventh round, heąd slowed his opponent to the point that he was

now landing a nice straight right to the head as well. The champion spent the eighth

holding onto the back of the kidąs neck, while the kid flailed away at his liver, his

hips, his kidneys, and whatever else fell to hand. And when at the end of the round

the championąs hand was raised, the crowd vented their displeasure with the decision by

whistling and gesturing with their machetes. My feeling was that while the kid had

won the battle of wills, he had clearly been outpointed, and I soon found myself arguing

the matter with some of the men who had met me with stony glares earlier that evening in

the plaza, all of us engaging in a heated yet amicable round-by-round dissection of the

bout.

Back at the hotel I fell into a conversation with the flyweight, who

was named Miguel. He was sporting a mouse under his right eye, but didnąt seem the

worse for wear. We talked about boxing, about Ali, Duran, Palomino, Napoles.

He was such a good-natured kid, always joking, smiling, I couldnąt imagine him making a

living in the ring (I'd never talked to a professional fighter before and didnąt realize

that most of them were quite different from their ring personas), and I asked what he

planned to do with his life. His smile vanished, he

fixed me with a gunslinger look and said he intended to become champion of the world.

I've always enjoyed watching Latin fighters. I admire their

aggression, their heart, the way they work the body. But until that night at the

movie theater in Santander Jimenez, watching the shadow of the light-heavyweight champion

of the Yucatan being chased about a flyspecked screen by a smaller, quicker shadow with a

mean left hook, I'd never understood anything about the obstacles the fighters I'd seen on

TV had to overcome. As I continued to travel around Mexico, I attended fights held

in makeshift outdoor rings, in pits normally used for cockfights, in corrals, in every

imaginable sort of venue. I saw guys wearing bruises and cuts from recent fights go

face-first at their unmarked opponents; I saw sixteen year old kids debuting against men

with 20 fights; I saw other kids substitute for injured boxers despite having fought a

bout earlier in the evening. Part of the mystique attaching to Latin fighters was

their toughness, and it was becoming clear how they got that way, and just how tough they

had to be in order to claw their way out of the backwaters and make it to money fights in

Mexico City and TJ and other such places, and--if they were really tough, really talented,

and really lucky--to the States.

About a year after the fights in Santander Jimenez, when I was

living in Merida, I was in a little ice cream shop on the plaza mayor, when I

spotted Miguel, the flyweight whom I'd watched in the movie theater, walking past.

I called out to him, and after an exchange of greetings, we grabbed a bench

and talked for a while. It was late

afternoon, and on the bandstand at the center of the plaza a brass band dressed in

military uniforms were playing a woefully inept rendition of the William Tell Overture to

an audience consisting of old men and shoeshine boys. Pigeons were strafing the

benches beneath the trees at the edge of the plazea where lethargic hippies relaxed in

the shade. Pretty Mexican girls were walking in groups of three and four, taking

their paseo, ignoring the boys who called after them, but quite a few waved and

smiled at Miguel--I began to have the idea that he was something of a big deal. I

asked how his boxing was going, and he said he had an important bout coming up with a

from Mexico City.

The next couple of weeks, at Miguel's invitation, I spent a good deal of time at his gym. He always acknowledged me with a grin, but we didn't talk much--he was intent upon his training. The gym was not what I was used to in the States. Much of the equipment was homemade. Handsewn heavy bags. Free weights consisting of axles to which lumps of iron had been welded. But it was one serious boxing place. From the old ex-fighters who kibitzed and gave advice to the trainers to the skinny-armed ten-year-olds who ran errands, everyone there was totally dedicated to the sport and to each other. There was a unity of purpose among the people who frequented the gym, a much tighter bond than any I'd experienced in gyms back home--it brought to mind the intense loyalty displayed by members of those fictive martial arts schools depicted in Bruce Lee films. At the moment the focus of all that intensity was Miguel. It was plain that he was the hope of the place, the guy whom they thought might bring them glory and maybe even some money, and when he was sparring or working the speed bag, the old dozers on the benches would come alert and the other fighters would stop what they were doing, and you could feel the push of their wills urging him on.

The fight was held late on a Saturday afternoon in the bull ring in Merida. Chairs had been set up on the sand around the ring; they were all filled, and the bleachers, too, were packed. By the time the main event started, the atmosphere had become electric, almost to the level of a bigtime title fight. Miguel had improved a lot since Santander Jimenez. For the first four rounds he dominated his opponent with his movement and quick combinations. The crowd was on its feet, yelling and shaking their fists. But then in the fifth he was headbutted and received a bad cut beneath the eyebrow. His corner was able to deal with the bleeding between rounds, but the cut kept reopening, his opponent continued to use his head, and since Miguel didnąt have the pop to take the guy out, he was forced into an increasingly defensive posture. As a result, he lost a close and controversial decision.

I didnąt see Miguel until a few days later. His eye had been

patched up, but he was otherwise unmarked--his opponent hadnąt done much damage with his

gloves. I thought he'd be depressed but he was strangely upbeat. He said that

his performance had proved he was capable of competing on a championship level. And

the controversial result? He shrugged. Politics, he said. He hadn't

expected to win a decision, But people in Mexico City would hear what had happened,

and he was confident that before long he'd be fighting in the capitol. I wasn't so

confident. I figured Miguel was going to be another one of the hard luck kids I'd

watched in boxing rings all over Mexico, and that his loss in the plaza del toros

was merely the first in a long line of bad breaks coming his way. I was

glad I wasn't going to be around to see it--I was due to head north in less than a month.

It occurs to me now that I shouldn't have been so concerned about

Miguel, because I'd witnessed numerous instances of his determination and dedication.

I recall one night we were drinking on the benches in a small square near my

apartment, hanging out with some guys Miguel knew who drove horse-drawn cabs. It was

the only time I ever saw him take a drink--he lived in shape; but he was having

woman trouble and was depressed. It must have been about one oąclock in the morning

when someone got the idea that if we drove over to his girlfriendąs house and serenaded

her, all his problems would be solved. Off we went, clopping along in one of the

cabs, drunk on our asses. By the time we reached the girlfriend's house Miguel had

passed out, but his friends decided that we had to serenade her nevertheless. None

of them, however, could stay on-key. Which is why I soon found myself leaning

against the neck of a horse, holding onto it to steady myself, and signing a mangled solo

version of "Guantamera" to a confused-looking girl standing in her nightgown

behind the wrought-iron bars of her

bedroom window.

Miguel regained consciousness as we headed back toward the center of

town; he seemed angry, and he insisted on being let off at the gym. He pounded on

the door until the old man who slept there opened up. I

went inside with him, thinking I'd catch a few hours sleep and thus be better prepared to

face the woman--doubtless an extremely angry woman--waiting for me at home. I

figured Miguel was thinking along

similar lines. He went to take a shower. I settled in a corner and dozed off.

Several hours later I was awakened by what proved to be shouts of effort.

Miguel was hanging from the chin-up bar by his knees, holding a large cement block

to his chest, and doing sit-ups.

On my way out of town I stopped by the gym to say goodbye to Miguel.

He gave me an embrace, then shook my hand and said God willing we would meet again

someday. But God wasn't willing, apparently. I never did see him again.

However, a few years later I did learn something about him. I was in a hotel bar in

Athens, the

other side of the world, when I spotted a boxing magazine that someone had left on the

counter. I thumbed through it and came to the page where all the champions and

contenders were listed. I'd been too busy to keep up with the sport for over a year,

and I was curious to learn what changes had occurred. When I looked at the lighter

weight classes I was startled to discover that the flyweight who had cast a shadow on the

movie screen in Santander Jimenez had come to cast a far more considerable shadow over his

division. Miguel Angel Canto had

become the WBC champion of the world.

Roberto Duran and the Horseshoe

By Rick Farris

In March of 1973, Roberto Duran, Lightweight Champion of the World, came to

Los Angeles to fight Mexican champ Javiar Ayala in a ten round non-title fight. The

match was on the same card with the WBC Lightweight Championship bout between title

holder Rudolfo Gonzales and challenger Ruben Navarro.

Navarro and I were stablemates and would often spar together. However, for

this match Ruben had a group of sparring partners whose styles were more like Gonzales

than mine. Two years previous, Ruben came close to upsetting then lightweight champ

Ken Buchanan but lost a close decision. This would be another opportunity to win a

version of the world title and he was taking no chances.

One day I arrived at the Main Street Gym shortly after Duran and Navarro had

completed their workouts. I talked to Ruben in the dressing room as I laced up

my boxing shoes. That day, Navarro had sparred with Duran and he seemed a

little different than usual.

One day I arrived at the Main Street Gym shortly after Duran and Navarro had

completed their workouts. I talked to Ruben in the dressing room as I laced up

my boxing shoes. That day, Navarro had sparred with Duran and he seemed a

little different than usual.

"This guy hits harder than anybody", Navarro said. "He hit me

high on the forehead with a spent jab and it shook me all the way down my back to my

toes". I had known Ruben for quite a few years and never heard him express

respect for another fighter as he was Duran. It was almost as if he was intimidated,

not in a cowardly sense, but in a way that caught me off guard. Navarro had

fought and beaten some of the best lightweights and Jr. lightweights in the world during

his career, so I had to believe what he was saying.

A few days later, I was in the gym at the same time as Duran and it was fascinating

watching him train. He skipped rope like nobody I'd ever seen, including the

great Sugar Ray Robinson. Duran could do things with a jump rope

that made for quite a show. However, the most entertaining of all (aside from

his sparring) was watching Roberto hit the speed bag with his head. I don't mean

just banging it back and forth, Duran could make the bag dance with his head as well

as most boxers do with their hands.

jump rope

that made for quite a show. However, the most entertaining of all (aside from

his sparring) was watching Roberto hit the speed bag with his head. I don't mean

just banging it back and forth, Duran could make the bag dance with his head as well

as most boxers do with their hands.

However, watching Duran spar was the real show. In fact, Duran didn't

just spar, he fought all out regardless of who he was in the ring with and it was

common for a sparring partner to hit the canvas and be out cold. When

Roberto would launch a body attack he'd fire vicious shots that would land with a thud.

He'd let out a "yelp" as the punch was delivered. The high pitched

noise coming from Duran's mouth would punctuate each blow and had an eerie effect. I

was impressed, to say the least, and privately thought to myself, "Glad I'm a

featherweight and won't have to fight this guy".

Little did I know that my manager had been talking with Duran's trainer, Freddie

Brown, and had agreed to let me spar with Duran. It wasn't something I had a

great desire to do, but a fighter doesn't show his feelings so when I got the news I

just acted like it was no big deal. I was told that the only reason I'd be working

with the larger Duran was for speed. I had fast hands and would provide

quickness for Duran. Brown had assured my manager, Johnny Flores, that

Duran would work lightly and not cut down on me.

Somebody must have forgot to tell Roberto the plan and about midway thru the opening round

I found myself sitting on the canvas. I got up quickly and was OK but it occurred to

me that I might be fighting for life. When the sparring resumed I understood

what Navarro had meant when describing Duran's power. It was awesome, and even

punches that most would consider average shots had something I'd never felt before.

It was like being hit with baseball bat. Duran had 16 ounce training gloves on

that looked to be padded, but it didn't feel like they were. This was before

Roberto had been tagged "Manos de Piedra" or "Hands of Stone" in

English. I can personally verify that this is more than just a nick name, it's a

fact!

Duran is a guy who considers the ring his personal domain and anybody who stepped in with

him was treated as if they were caught breaking into his home. The ring was Duran's

office and he'd establish this immediately with anybody who entered, including me.

After the three rounds of torture with Duran, I punched the heavy bag. The champ

finished sparring with two other boxers, a lightweight and a welterweight who was beaten

so badly he left the ring trembling. After Duran stepped out of the ring

Freddie Brown untied the champs gloves and pulled them off. I was resting between

rounds on the heavy bag and moved closer to Duran to get a look at his hands.

There had to be something harder than a fist inside the gloves and I wanted to see what it

was.

Brown glanced over at me and said something to Duran in Spanish and the two

began to laugh. I asked Brown "What did you say to him"?

Brown just looked at me with a smile and answered, "I told him you were looking

for the horseshoe".

Brown glanced over at me and said something to Duran in Spanish and the two

began to laugh. I asked Brown "What did you say to him"?

Brown just looked at me with a smile and answered, "I told him you were looking

for the horseshoe".

I had to laugh, but honestly, that's exactly what I was doing. However, The

only thing I found in Duran's gloves were his fists. Or as they would later be

known, "Hands of Stone".

About a week later, at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, my friend and stablemate Ruben

Navarro was stopped by Rudolfo Gonzalez in his last attempt to win a world title. In

the fight before the title match, the real lightweight king Roberto Duran battered

Javiar Ayala savagely and won a unanimous ten round decision.

With the feel of those rock hard fists still fresh in my mind, I knew that Javiar

Ayala discovered the same thing that Navarro and I had just days before.

The horseshoe had nothing on "Hands of Stone"

Interview With Marvelous Marvin Hagler

By Dave Iamele

You're Marvelous Marvin Hagler. You are the middleweight champion

of the world, an honor you've held since 1980. In those seven years, you have

successfully defended your title 12 times, ko'ing all of your foes except for future Hall

of Famer, Roberto Duran. You have been one of the very few undisputed champions of

the 1980's. You must be a happy guy, right? No. On this April night of

1987, happy you ain't. After a career that seemed to triumph over one screw

job after another, tonight should have been your crowing moment. This should have

been the defining moment of your career. Instead it's just one more screw job.

The last screw job. Disgusted after coming out on the wrong side of a bad

decision against Ray Leonard, you turn your back on boxing. Forever. No

come backs. No one-more-times. Done.

5/18/73 - 4/6/87

67 bouts 62 wins 3 losses 2 draws 52 ko's

Over twenty years later, I sit sweating in the motel lobby of

Graziano's. It's June in Canastota, and the Hall of Fame is hopping. I'm

waiting. Been waiting. I'm surrounded by my gear: tape recorder,

cassettes, mic, boxing mags, interview notes, pens, boxing cards, posters, x-tra

batteries, card sleeves, cigars, beers (in portable cooler), etc. I'm hot and

getting a little cranky. I'm sweating up the suit I just had dry cleaned.

Agonizingly, I can see the cool comfort of the air conditioned bar only a few short feet

away. I can almost taste the beer. I've been waiting for Joe Frazier for a

long time. Too long. As I'm debating over leaving or cracking open a cold one

from my supply, a bus pulls up. Who steps out? You do, of course. The

Marvelous One. I ask. You oblige. Your thoughts --

DI: "You made more middle weight title defenses than anyone except for Carlos Monzon.

. ."

MMH: "Well, I tried. I was one fight away from conquering the

record of Carlos Monzon. Monzon held the title for 10 years. Over 7 1/2 years,

I was already close to beating that record. I felt as if I could have done that

(beaten the record for most title defenses - 14) but you know what the outcome was.

The controversy with the Sugar Ray Leonard fight. But it probably was for the best

because I would've continued because I was only another fight away from making history in

a sense."

DI: "You were known as a devastating puncher, and excellent boxer and you adapted

well defensively to your opponents. One of the best of your time. Yet,

originally, you didn't want to be a boxer, you wanted to play baseball?"

MMH: "No. I played all sports in

school. I was very fortunate, in a sense, to find boxing, because you had to

have the education to play baseball or basketball in college. In boxing, you didn't

have to have that, you just had to have that street (toughness). I was too small for

football. Boxing was just made for me. I think I was born to be a

fighter."

MMH: "No. I played all sports in

school. I was very fortunate, in a sense, to find boxing, because you had to

have the education to play baseball or basketball in college. In boxing, you didn't

have to have that, you just had to have that street (toughness). I was too small for

football. Boxing was just made for me. I think I was born to be a

fighter."

DI: "Floyd Paterson was one of your heroes when you were coming up?"

MMH: "Floyd Patterson is STILL one of my heroes. He was one

of my idols. Also Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. . .Bob Foster. . . This is why

I enjoy coming to the Hall of Fame, because I get a chance to see my idols. You get

a chance to sit down and talk and just hang out with them. It's a nice

feeling."

DI: "That's what the fans enjoy too. You didn't get a title shot until 1979

against Vito Antuofermo and then they called the bout a draw. Why did it take so

long for you to get a title shot? Didn't the Petronelli brothers have the

connections?"

MMH: "No. It's because we never kissed butt and that's what

happened. It's the same thing that's happening to me now in my film career. I

find out it's the same game. It's who you know. If you kiss butt, your career

moves along a little faster. That's what happened to me with the title shot. I

didn't kiss butt. Another thing is I was a dangerous fighter. At least I was

very happy that Antuofermo gave me the opportunity to fight for the title. I felt

that I won that fight, but the decision was a draw. I always said that if anything

ever happens the way that it happened with Antuofermo and me, with him being able to keep

the belt because he was the champion. . . well, with me in my last fight with Ray

Leonard, they seen what happened to me in the title fight with Antuofermo, and I was

hoping that if it ever happened to me, it would go in my favor. Which it

happened, and you know the outcome of that."

DI: "You didn't waste much time letting the draw get you down. Less than a year

later , you went over to England and ko'd Alan Minter in three rounds to capture the world

middle weight title. . ."

MMH: "I was the number one contender. I was the number

one contender for three years (laughs). Unbelievable!"

DI: "Yet, after you won the title, every fight was a title defense."

MMH: "And every one was against the number one contender."

DI: "You never ducked anyone."

MMH: "That's right. I was very happy the way I finished my

career. There's no one out there that can say I ducked them. We gave everyone

an opportunity to dethrone me and prove who was a better fighter."

DI: "In all those defenses, you ko'd everyone except Roberto Duran. That's

pretty impressive."

MMH: "Well, you see, Roberto Duran was a different kind of fighter.

Roberto Duran was a three time champion, he had the speed of a welterweight.

. . he had a lot of experience. . . for me. . . I enjoyed that fight, more than anything.

The first few rounds, I couldn't understand, because Roberto still had the speed. .

. but after I started to figure out his style and to show him that anything he could do, I

could do better. To go the distance, the full fifteen rounds, that was to show you

that I was the true world champion."

DI: "In your career, you didn't seem to make out too well in Philadelphia. You

lost home town decisions to Bobby Watts and Willie Monroe there. What is it about

you and Philly? It must not be your favorite town."

MMH: "Philadelphia was the land of opportunity for me when I look

back. All those guys could've been champion of the world if it wasn't for me.

I still respect all those fighters because they were all top rated guys, you know, Cyclone

Hart, Bad Benny Briscoe. . . I mean, when you get past these guys, then you know.

That was my test to show my true ability. To show that I had what it took to be a

true world champion."

DI: "You revenged both of those losses with Watts and Monroe later. . ."

MMH: "Well, you know, with the first Watts fight, I thought that

wasn't right and with the Willie The Worm fight, I made no excuses - I've never made

no excuses, I had bronchitis at the time and my trainer didn't even want me to take the

fight. But there were just two weeks until the fight and it was an opportunity, you

know? I mean, he was rated #3 in the world and you get by this guy, maybe you get a

shot at the title. And that's what I wanted, a shot at the title."

DI: "So, basically, you retired undefeated, truthfully."

MMH: "I feel that way. Even the last one (the Leonard bout),

which was very hard for me to swallow, because I know in my heart that this guy never beat

me, but you know the controversial decision. I felt that with a little luck . . .

that the luck should go on my side. . . but I never had any luck in the boxing game

(laughs). I just got tired of the politics and everything, and I just said `forget

it', you know."

DI: "I remember we listed to the fight on pay-per-view. We didn't pay for it,

so the picture was all scrambled but back then, you could still hear it. So it was

like listening to it on the radio. Anyway, we certainly had the impression that

you had won the fit, and I can remember everyone was shocked when they announced

that Leonard was the winner. Having watched the bout several times since, I think

you clearly won the fight. You got robbed."

MMH: "Well, I think there's no way in the world, even by being the

champion - talking about Antuofermo again - where in a draw, the belt went to the

champion. If you don't knock the champion out or you don't beat the champ

convincingly, the title still remains with the champion. That's a lesson I

learned the hard way. So then I knew what it took for the last fight. There's

no way, I mean when I was finished with the Ray Leonard fight, I came out without a scar,

without a swollen lip, not nothing. I mean, if you've seen the fight with me

& Mugabi, I mean I was a mess. It was a very hard fight. But these guys

came to fight, came to take away my title. This guy (Ray Leonard) only came to

survive."

DI: "You were a very active fighter until 1981, then you only had 3 or less bouts a

year from 81 - 87. Why?"

MMH: "That had nothing to do with me. That depends on the

manager and trainers. That's what they wanted to do, so that's the way I went."

DI: "People wondered why you never came back after the Ray Leonard bout or why there

was never a rematch. Were you just sick of getting screwed?"

MMH: "I got screwed all my life! I mean, you know the boxing

game, and I just got fed up with it. We did wait around for another year hoping that

Leonard would give me a return match, and I think if the shoe was on the other foot,

I'd have given him the return match. I think this guy was just waiting around for me

to get older, then he felt he'd have a better chance. But you know, I was

still very strong when I retired, and I still felt very good, but you know I waited a

year, and when I saw he wasn't gonna give me a rematch, I decided that life has to go on,

and I have to find another career. Which is what I've done now with the movies and

now that's what I'm chasing - It's like another title fight but now an Oscar is like a

championship title (laughs)."

DI: "How's that going over in Italy?"

MMH: "It's going very good, you know. But it's still hard.

You can get discouraged, but I think the boxing games helped me to keep

strong and focused. I believe that if I put the discipline, the sacrifice, the

determination that I put into boxing into this, then something's gotta come out very

good."

DI: "One last question, Champ. . ."

MMH: "I've only got four films under my belt right now. I always

felt when I was doing a film, it's like the beginning of a boxing career. So I'm

like in my fifth round (laughs)!"

DI: "So you play kick-ass guys like Van Damme and Chuck Norris?!"

MMH: "Yeah. I like the action/adventure type of films.

I like to stay in focus and in front of the fans. I have a lot of fans and people

wonder, `where did Marvelous Marvin Hagler go?' Now, my fans can go to the movies

and still see the kid. I hope I can do as great a job in movies as I did in the

ring. Another thing I'm trying to do is show boxers that there is another life after

the ring. You don't have to be making comebacks. I mean the money ain't all

that great, but I'm having fun making movies. That's what's good. Anything

that you do, if you're having fun, then it's good."

DI: "And you're not getting your head punched in."

MMH: "That's even better, not takin' a punch."

DI: "Thanks for your time, Marvelous."

MMH: "Anytime, thank you."

So the tape stops, and I pick up my gear. Marvin graciously signs

a couple of boxing cards for me, and I take off after another interview, or a least a cold

beer. I never did get Joe Frazier to sit down for an interview, but I got a chance

to speak with the Marvelous One because of him, so Joe's all right by me. If Marvin

never wins his Oscar or isn't quite Clint Eastwood, it won't be because he didn't give it

his all. And he was Marvelous in the ring, Lord he was.

Bruno on Boxing

By Joe Bruno---Former vice president of the Boxing Writers Association and the International Boxing Writers Association

Like Yogi once said, it was deja vu all over again.

It what was probably the most stunning decisions since General Custer

decided to take on those pesky Indians, Felix Trinidad was awarded a majority decision

over Oscar de la Hoya on September 18th in Las Vegas. Judge Jerry "Robber" Roth

scored it 115-113 and "Burglar" Bob Logist had it 115-114, both for Trinidad.

Glen "Highwayman" Hamada had it at 114-114, a draw.

The Don King-bought Vegas judges perpetrated a bigger travesty than their counterparts did in New York City after the Lennox Lewis-Evander Holyfield heavyweight fight earlier this year. At least in the heavyweight fiasco that took place in New York City, Lewis got a draw. That fight produced an investigation into the honesty of the boxing judges. The De la Hoya-Trinidad robbery should mandate the same, but the fact is, everyone in the town that Bugsy built is so giddy about a possibly rematch and another huge payday, no one gives a hoot anyway.

Just look at the ludicrous scoring of Judge "Robber" Roth.

This crook gave Felix Trinidad three of the first four rounds, when in fact, it was hard

to make a case that Tito won any of the first nine rounds.

Gil Clancy, who worked as an advisor in De La Hoya's corner said

afterwards, "I'm shocked. Don't those people (judges) know good boxing when

they see it?"

Sure they do Gil. But they see more lucrative paydays in their

pockets, if they vote for the right (the Don King-owned) fighter, much more distinctly.

The fight went simply like this. De la Hoya won the first nine

rounds easily. He out jabbed, out punched Trinidad, and he seemed able to take out Tito

anytime he wanted. The tenth round was razor close, so I gave it to

Trinidad, just for showing up.

Before the eleventh round, Clancy, one of the most savvy trainers in the history of boxing, told De la Hoya to "simply box." The implication was that Oscar was so far ahead, only a knockout by Trinidad could give him the fight.

Clancy's advice was on the mark. De la Hoya did what he was supposed

to do in the final two rounds. He boxed and stood out of harm's way.

Like the Holyfield fight, I watched the fight over Neil's house in

sunny Sarasota, Florida with friend Felix. We all were hoping to see the much publicized

"fight of the millennium." Instead we saw a masterful, but sometimes boring,

boxing display by De la Hoya that made most purists giddy. The intermittent booing in the

arena was probably caused by the Vegas high rollers who bet big cash on Trinidad,

and were watching their money flush

right down the drain.

After the fight Neal, Felix and I all scored the fight the same way; 117-111 ( 9 rounds to 3 )in favor of De la Hoya. There was nary a doubt in our minds. but before the decision was announced, I told them like I did after the Holyfield fight, "Don't laugh guys, but Don King bought at least one judge. I bet one judge scored the fight a draw."

Neal and Felix laughed heartily again, but not with the same conviction

as they did after the Holyfield-Lewis fight. I proved to be prophetic again when

"Highwayman" Hamada's scorecard was announced.

But never in my wildest imagination was I ready for what I heard next;

the other two crook judges giving the fight to Trinidad.

I rushed to my computer the following morning to read what other boxing

scribes around the country had thought about the decision. Only Mike Katz of the New York

Daily News, (who has a running feud with De la Hoya and constantly calls him

"chicken"), scored the fight a draw. Everyone else had it for De la Hoya. Some

had it closer than I had , but all for De la Hoya nevertheless.

Then I turned on the Sports Reporters on ESPN and New York Daily

News diminutive sports columnist Mike Lupica (I'm being kind. The man's Pee Wee Herman,

but not as tough) actually said, "I thought Felix Trinidad won the fight."

Now I felt much better, since this is the same Mike Lupica whom I

never saw at a single fight, or boxing press conference that I covered in New York

City from 1978-1989. To Lupica, boxing and most fellow sportswriters are way beneath him.

Lupica's a member of the elite, Fourth Estate pseudo-intelligencia, who look upon us peons

as if we are hemorrhoids on the backside of society.

After the fight, Oscar had a stunned incredulous smile pasted across

his handsome face. He said, "Trinidad is a very strong fighter. I am hurt inside

emotionally. Honestly in my heart I thought I won the fight. I really believe

I was giving him a boxing lesson, but apparently it wasn't appreciated by people (the

judges). I really believe I was in control of the fight.'

"Give him the last four rounds and it is still 8 to 4," de

la Hoya added. "I feel in my heart that I tried to box and give a good lesson. The

people at ringside didn't see that. I thought I had it in the bag, I swear in my heart I

had it in the bag. I was never, ever hurt. I really, really felt he was hurt

two or three times. But still, the strategy was not to knock him out. I was

not even thinking of knocking him out."

De la Hoya wasn't the only person in Vegas stunned and hurt

financially by the three unscrupulous judge's decision. His promoter Bullspit Bob Arum

said afterward, "I don't know what the hell people are looking at scoring a bout. I

have never been so damn stunned. There was a lot of talk about Oscar not being able

to lose a decision in Las Vegas, I think the judges went in with that mind set. If

you win eight of the first nine rounds, it should be in the bag."

Guys, it was in the bag. Don King's bag, you fools. In fact, in the ring after the decision was announced, King, with his usual mocking style, told Oscar, "You see, what you need is a better promoter."

A promoter more capable of influencing (buying?) the judges.

The bottom line is this. Boxing people who understand what they were

watching, and actually know how to judge a fight, all had it bigtime for Oscar. The

others, some who see a fight as often as Halley's Comet makes an

appearance, or have a personal dislike for Oscar that clouds their judgment, either had it

a draw, or somehow scored the fight for Trinidad because he was moving aggressively

forward for most of the fight.

The operative word here is "effective aggressiveness."

Effective aggressiveness (De la Hoya), clean punching (De la Hoya), defense (De la

Hoya), and ring generalship (De la Hoya), are the four criteria supposedly used to judge a

fight. (The great Willie Pep once won a round without throwing a single punch because his

defense was so spellbinding.)

If you are a stickler for statistics, CompuBox had De La Hoya

landing 263 of 648 punches, Trinidad 166 of 462. (41% to 36%) Oscar landed 97 more

punches, and the harder blows throughout the fight were consistently landed by De la Hoya,

especially his piston like left jab, which seemed nailed to Tito's nose throughout the

first nine rounds. The only power punches of any note landed by Trinidad were fired in the

last two rounds.

So kiddies, save up your pennies. The rematch is in the bag too. The only

person who can gum the works is De la Hoya himself. Oscar could retire and tell them all

to shove it. But don't count on it. Oscar has pride, and the fear of being called chicken

by more people than Mike Katz, should be enough to force him to fight Trinidad again.

There is a precedent for a champion never fighting again after being

screwed in Las Vegas. After he was robbed in a twelve round fight against then-Golden Boy

Sugar Ray Leonard in 1989, Marvelous Marvin Hagler decided to star in action movies in

Italy rather than submit himself, his pride, and his fight record to the rogue Las Vegas

judges. If the next time they meet, Oscar greats Hagler with a "caio paisan",

then his proposed rematch against Trinidad could go right down the crapper.

Show real guts Oscar. Not intestinal fortitude, which most fight

fans know you have anyway. Use the fortitude of your mind. Tell them all to take a hike.

Make commercials. Make movies. Make Spanish albums. But don't give them what they (King)

want so dearly; a chance to screw you, and the paying public again.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I hate to say it, but this one was a pleasure to watch.

Former great champion Julio Cesar Chavez had his clock totally cleaned

by club fighter Willie Wise on the undercard of the Ricardo Lopez-Will Grigsby title fight

in Las Vegas on October 2nd. Wise won virtually every

round, completely dominating Chavez, and almost knocking the Mexican legend down twice. If

Wise had been a bigger banger ( he has only has seven career knockouts), Chavez would've

surely been blasted out. The judges scorecards were unanimous for Wise, 118-111,

117-111 and 116-112. How anyone gave Chavez four rounds is another example of the

criminal judges in Las Vegas. The online scoring tabulated by Showtime had it 10-0 for

Wise. This reporter had it 9-1 for Wise, giving Chavez only the first round.

As usual, Chavez made excuses for his poor performance.

Through swollen lips Chavez said after the fight, "Wise got his

confidence against me and I was preparing for an easy fight."

Then Chavez hinted he might be foolish enough to try to fight again,

the next time against a banger like junior welterweight champion Kostya Tszyu.

"I am still the challenger for the junior welterweight

title," Chavez

said. "Preparing for a championship fight is a lot different than for an easy

fight like this."

Easy fight? Maybe Chavez was hit a lot harder than it appeared.

If Don King is greedy enough, and of course he is, and Chavez stupid

enough (this one's up for grabs), a fight against Tszyu could be suicidal for Chavez.

It won't be a pretty sight.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Talk about the pot calling the kettle black.

This shocking tidbit was in a New York Daily News, written by TV

columnist Bob Raissman. "In a letter to the Miami Herald, Showtime boxing analyst

Ferdie Pacheco ripped into TVKO's coverage of Felix (Tito) Trinidad's

win over Oscar De La Hoya. Pacheco accused TVKO's announcers of being pro De La Hoya, and

directed much of his wrath at the guys from CompuBox who keep the punch stats. He claimed

they work for Bob Arum, De La Hoya's promoter."

The two guys Pacheco is slinging mud at are Logan Hobson (previously

a boxing writer for the now-defunct United Press International), and Bob Canobbio,

co owners of Compubox. I've known Logan for twenty years (and Bob for the last fifteen

years. I distinctly remember telling both that this punch stat thing would never work (I

also thought General Custer was right about those damn Indians). Both Logan and Bob are

above reproach. They work only for themselves, and in this business of counting punches,

integrity and good eyesight are of the utmost importance. Bob Arum is not their friend. if

anything, both are closer to the Duvas, and they don't give the Duva's

fighters a break either.

But this fraud Pacheco, "The Fright Doctor," has been

nothing but a shill for Don King for years. Listen to Pacheco working a fight on Showtime,

or a pay-per-view promoted by King, and right away you know which fighter Don King wants

to win. It's like the other fighter is not even in the ring. In the journalism business,

his peers rank Ferdie Pacheco somewhere below President Clinton for integrity, and Donald

Trump for shamelessness, and that's saying a mouthful.

If Don King ever gets forced out of the boxing business, Pacheco

might have to get a job shilling the freak show for Barnum and Bailey's. For that Pacheco

is eminently qualified.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I'm not sure if this falls

under the category of "man bites dog", or "dog might bite man again."

I'm not sure if this falls

under the category of "man bites dog", or "dog might bite man again."Former heavyweight Mike Tyson, who chomped off part of Evander Holyfield's ear in a 1997 title fight, said if a referee fails to protect him in his next bout, he would react in the same way. "I would do it again under those circumstances,'' Tyson told the Los Angeles Times. "Referee Mills Lane wasn't protecting me from head butts. He didn't handle the situation appropriately.''

Tyson continued his self-serving diatribe with, " In

retaliation, I'll fight back because nobody is fighting for me. I have to defend myself.

It is just human nature to defend yourself. Nobody ever has any sympathy or pity

for me."

Wrong, Vampire teeth. I know one boxing columnist who thinks you're

unfairly labeled "America's Bogey Man." The same columnist probably thinks

President Clinton's didn't inhale, or have "sexual relations with that woman, Miss

Lewinsky."

Still, one thing's a lock. The Las Vegas commission, who

reinstated Tyson's boxing license after a 15 month suspension for the above bite, is on

pins and needles waiting to see if Tyson goes (biting) berserk again against

Orlin Norris later this month in Vegas. If Tyson does resort to form "protecting

himself", the commission is sure to give Tyson more than an just an earful.

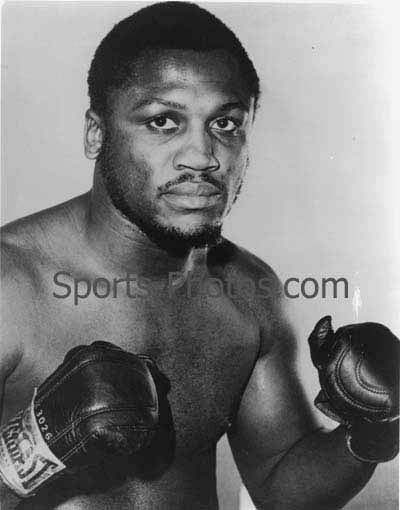

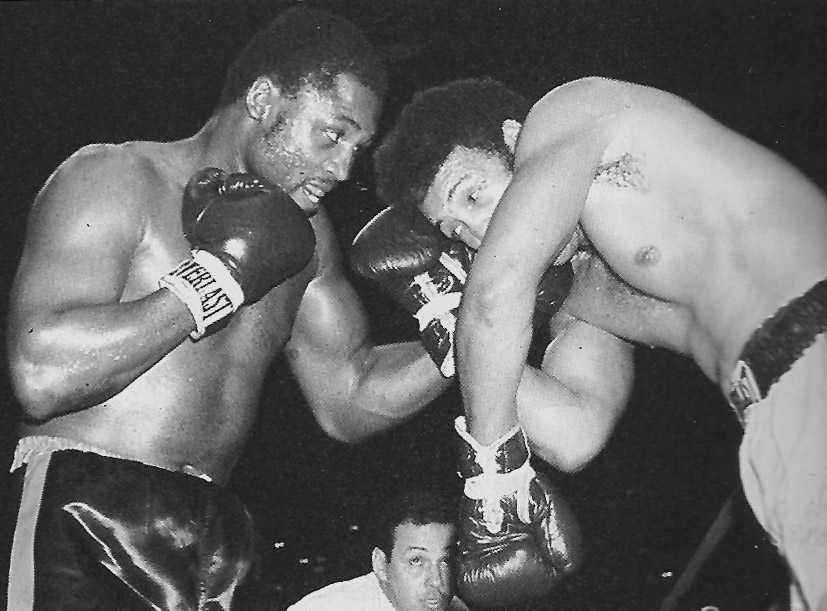

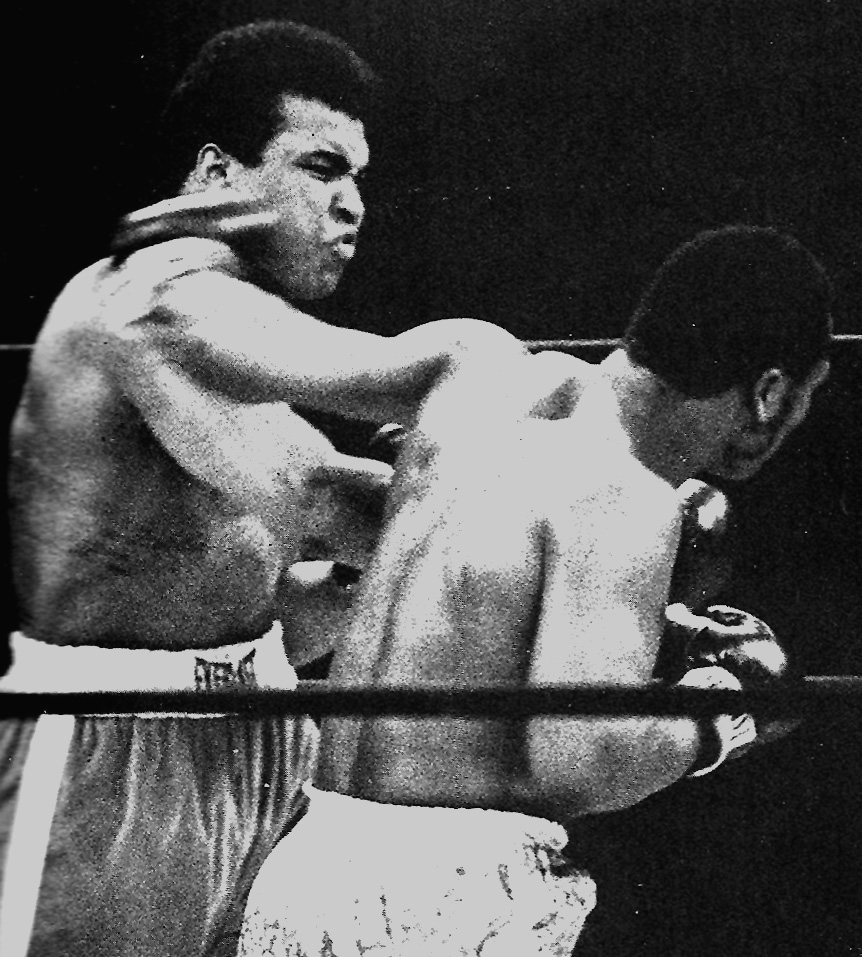

JOE FRAZIER … "SMOKIN’ JOE – THE BLACK MARCIANO"

By Tracy Callis

Joe Frazier "came out smoking" at the opening bell and was still smoking 15 rounds later if necessary. He was a swarming, non-stop, perpetual motion attacker who fought from a crouch. A sturdy man with a tough jaw, powerhouse left hook (his right wasn’t bad either), and tremendous endurance, Joe came straight at his man, bobbing and weaving as he moved in.

Smokin’ Joe wiped out most competition easily and quickly. Only the better fighters could go any distance with him. He won the title "by degrees" following the action which stripped Muhammad Ali of the crown. New York state first recognized him as champion and, as he beat man after man, popular opinion considered him to be the best heavyweight around. Finally, in 1970 he knocked out Jimmy Ellis to become THE world champion.

Only two men defeated him in the professional ring – Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. Frazier fought three bouts with Ali, winning one without question and losing two, both of which were extremely close. He and Ali went 41 rounds against each other and Joe never left his feet. Only two men ever knocked him down – George Foreman and Oscar Bonavena (both men well over 200 pounds).

On the other hand, he is one of only four men to knock Ali down. He knocked out George Chuvalo who had never been stopped. He flattened huge Buster Mathis. He leveled the lighter, faster Bob Foster. All of this goes to show Joe’s power and quickness.

Stockton (1977 p 92) wrote that Frazier "… was an excellent body puncher and relied primarily on his powerful left hook. He exerted constant pressure and was fairly hard to hit with his bobbing and weaving style. He had no trouble with cuts and took a good punch."

Houston (1975 p 126) said "Frazier is murder at close and medium-range, ripping vicious hooks and uppercuts to the body and switching to the head, often snorting and grunting as he punches."

Litsky (1975 p 111) described Frazier as an "aggressive, relentless fighter who withstood punishment so that he could get close enough to his opponent to deal out punishment."

Cosell (1973 p 218) called him "… a very good, very tough fighter." Carpenter (1975 p 136) said Frazier was "pure aggression."

Muhammad Ali said "Frazier is not a great boxer. He is just a

great street fighter" (see McCallum 1975 p 75).

Muhammad Ali said "Frazier is not a great boxer. He is just a

great street fighter" (see McCallum 1975 p 75).Henry Cooper, British heavyweight, paired Frazier with Sonny Liston saying, "They were slugger-killers from the hard American school". He added, "You could hit Frazier with your Sunday punch and you could break your hand" (see Atyeo and Dennis 1975 p 82).

Yank Durham, Frazier’s manager, said the things that separated Joe from other good fighters were his determination and strength (see Durant 1976 p 165).

Durant (1976 pp 166 226) wrote "Joe’s great strength comes from his massive shoulders and huge arm and thigh muscles." He described the third Ali-Frazier bout as "… one of the roughest, most dramatic championship bouts ever staged."

Frazier is often compared with Rocky Marciano since their fighting styles were extremely similar. Joe was bigger than Rocky in physical dimensions but whether he was bigger on punch or chin is debatable. Odd (1974 p 68) wrote that he was correctly called the "Black Marciano" due to his physical make-up, fighting style, strength, durability, and punching power.

Atyeo and Dennis (1975 p 82) wrote "Joe Frazier was - perhaps still is – a master slugger, a throwback to the days when men fought each other with bare fists face to face across a chalk mark on the floor. His nickname ‘Black Marciano’ was an apt description, for like ‘The Rock’, any finesse Frazier had in his squat chunky body was entirely eclipsed by his unshakable determination to knock out his opponent."

McCallum (1974 p 343) likened Joe unto Marciano saying they were built alike and fought alike, using a "jungle technique." He goes on to say that Joe was not vulnerable to cuts like Rocky was.

McCallum (1975 p 74) wrote "Like Marciano, Frazier came to fight." He added "Joe was dedicated in his

training just as Rocky was.

Both of them trained as they fought and their gym fights were wars. They were willing to

take a punch to land one of their own. Both men smashed away at the body to soften up an

opponent and to open up the head defenses."

training just as Rocky was.

Both of them trained as they fought and their gym fights were wars. They were willing to

take a punch to land one of their own. Both men smashed away at the body to soften up an

opponent and to open up the head defenses."Grombach (1977 p 89) wrote that Frazier was often compared to Rocky Marciano because of high dedication to training and explosive punching.

Teddy Brenner, former matchmaker for Madison Square Garden, said "Frazier throws more punches and throws them faster than Marciano" (see McCallum 1974 p 343).

Cooper (1978 p 151) wrote "Joe was a better fighter than a lot of people believed. There wasn’t a lot of finesse with him, but he was something akin to Marciano" and added "Remember this … He fought Ali when Muhammad was at his best, and he even beat Ali with the title at stake."

Gutteridge (1975 p 35) argued "… Frazier, I am convinced, was strong enough to have walked through many of the idolized heavies of yesterday."

In the opinion of this writer, Frazier was one of the all-time great heavyweights. For sure, he was strong enough to have walked through many of the idolized heavies of yesterday.

References:

· Atyeo, D. and Dennis, F. 1975. The Holy Warrior – Muhammad Ali. New York: Simon and Schuster

· Carpenter, H. 1975. Boxing: A Pictorial History. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company

· Cooper, H. 1978. The Great Heavyweights. Secaucus, New Jersey : Chartwell Books, Inc.

· Cosell, H. 1973. Cosell. Chicago: The Playboy Press

· Durant, J. 1976. The Heavyweight Champions. New York: Hastings House Publishers

· Grombach, J. 1977. The Saga of Fist. New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, Inc.

· Gutteridge, R. 1975. Boxing: The Great Ones. London: Pelham Books Ltd.

· Houston, G. 1975. SuperFists. New York: Bounty Books

· Litsky, F. 1975. Superstars. Secaucus, New Jersey: Derbibooks, Inc.

· McCallum, J. 1974. The World Heavyweight Boxing Championship. Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Book Company

· McCallum, J. 1975. The Encyclopedia of World Boxing Champions. Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Book Company

· Odd, G. 1974. Boxing: The Great Champions. London: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited

· Stockton, R. 1977. Who Was the Greatest. Phoenix: Boxing Enterprises

Power Punches

By Lee Michaels

October

8 and October 9, 1999 - two of the most historic dates in one of the biggest farces in

sports: women's boxing.

October

8 and October 9, 1999 - two of the most historic dates in one of the biggest farces in

sports: women's boxing.On Friday, October 8, Laila Ali, daughter of Muhammad, made her debut in boxing a successful one, knocking out her unheralded opponent, April Fowler, 31 seconds after the opening bell.

The next evening, boxing history was made when the "Sweet Science" staged a rotten event, a battle of the sexes. Margaret McGregor, 5-foot-9 and weighing in at 129 pounds, squared off against Loi Chow, 5-foot-2 and 128

pounds in a 4-round exhibition. I would tell you the result, but I decided not to wait until the bout was over to write this column. Why? Because the outcome is irrelevant.

As was the debut of Laila Ali. For those of you who recognize women's boxing as a legitimate sport, I apologize. I apologize because you are so ignorant in your reasoning. And just what is that reasoning? Is it that Laila Ali will

bring a legitimate woman's name to the sport? That a woman fighting a man will prove that both sexes are equal at everything they do? That fighters like Christy Martin and Lucia Riker can actually box and should therefore be

recognized as legit fighters?

Let's investigate for a moment. In men's boxing, the best defensive fighter is Pernell Whitaker. In women's boxing, the best defensive fighter is….

Hence, my point. There is no defense in women's boxing! There is no technique

in women's boxing. My evidence - the most popular woman's boxer ever, Martin. Martin is

one thing and one thing only: a brawler. A brawler with a straight-ahead style who gets

hit and bloodied rather often. Yet she is the king of her domain.

Hence, my point. There is no defense in women's boxing! There is no technique

in women's boxing. My evidence - the most popular woman's boxer ever, Martin. Martin is

one thing and one thing only: a brawler. A brawler with a straight-ahead style who gets

hit and bloodied rather often. Yet she is the king of her domain.Actually, technically speaking, she isn't. Lucia Riker is easily the most complete boxer/slugger in the sport. But she's the only one. Sure, many women claim to be her equivalent, but where are they? Why haven't we seen them yet? Lack of recognition, you say? Correct, you are. However, you left out a comment before "lack of recognition." Lack of talent.

Which leads to the disgusting display between McGregor and her male opponent. What needs to be addressed first is this pitiful excuse of a human male known as Loi Chow. I personally would like to thank Mr. Chow for not only setting a wonderful example for humanity, but for disgracing males like myself who were taught not to hit a woman. In a world where hitting a woman is a sin, Chow volunteered to do so in a very public forum. Sure, McGregor agreed to this, but her motivation was obvious. She wanted to prove a point, that a woman can beat a man at his own game. What point did Chow want to prove? That man now has a new arena in which to beat up a woman besides the privacy of a home?

Mr. Chow, I wish I could e-mail this to you, you pathetic human being. You are not only a disgrace to society, you are also a disgrace to the thousands of men who actually attempt to make boxing a legitimate sport, as hard of a job as that is.

As for McGregor, you too are a disgrace. A disgrace to the women who are at least attempting to legitimize their "sport." It is actions like this which will prevent women's boxing from being able to stage competitive, safe fights. Rather than McGregor search for a semi-formidable female opponent like most female fighters do, she took the high road. And because of that, she made a laughable "sport" even more laughable.

Laila Ali's situation is not laughable, but at this stage in the "sport" of women's boxing, the only attention she can bring to it is negative attention. She is 21 years old, and before October 8th, had never fought in a boxing match of any kind, amateur or professional. She is also 5-foot-10 and 166 pounds, which is gigantic for a female fighter. Finding legitimate opponents at her weight class will be nearly impossible. Sure she could lose 30-35 pounds and fight Martin or Riker, but that's more fantasy than reality. So who is there for her to box that will both legitimize both her career and the "sport" in general?

I'm still waiting for the answer, folks.

Therefore, Laila Ali, until proven otherwise, is only a name with absolutely no boxing credentials. And now all of a sudden she is the future of her "sport." How sad.

Let's accept the facts. A woman, in physical terms, was not created to take the physical punishment that boxing so often dishes out. A woman's breasts are not meant to absorb punch after punch after punch. Further more, a

woman's breasts are not meant to be stuffed under some sort of protective boxing gear and THEN pounded with punch after punch after punch.

In order for women's boxing to become legit, more attention needs to be directed towards their training methods. It all begins in the gym. Once stamina and technical skills are correctly taught to the female boxing population, then the pool of legit female boxers will increase.

Until then, female boxing will only be a spectacle, the equivalent of the men's Toughman Contest.

Even more important is that it's also a tragedy waiting to happen. One day, the all-offense/no-defense style of women's boxing will come back to haunt the "sport." A bout will occur where one or both opponents show no defensive skills at all. Someone will get seriously hurt, media coverage will ensue, and then wham! Another tragic black eye for the sport of boxing.

What will happen then?

I'm still waiting for the answer, folks…

Jabs and Uppercuts

A few feelings about some legit boxing items…

…Just to put my two cents in, Felix Trinidad did not win his bout against Oscar Dumb La Hoya. Dumb La Hoya LOST the bout. Question for Oscar: If you so outclassed Trinidad by out-boxing him in the first eight rounds of the fight, would it have been asking too much for you to do so for the final four rounds? By doing so, you would have left no question marks with the three judges. The outcome would have been signed, sealed and delivered in your favor. Instead, Team Dumb La Hoya executed one of the worst strategic moves in the history of championship boxing.Even more disturbing about Dumb La Hoya was his recent appearance on "The Tonight Show" with Jay Leno. Oscar said he wanted to put on a boxing clinic that night to prove to everyone that he could box, move and defend himself. However, Oscar added that the fans were not accepting towards his style, so he will go back to the brawling style he used against Julio Caesar Chavez in their second bout. Seeing that future opponents for Dumb La Hoya may include such names as Trinidad, Ike Quartey, Fernando Vargas, David Reid and Shane Mosley, just to name a few, this doesn't seem to be a good idea. Simply put, this is a fighter without neither direction or security in the boxing world.

…Speaking of Mosley, the only thing I can see holding him back in the welterweight division is pacing and stamina. Against Wilfredo Rivera, Mosley tried to do too much too soon and got tired early. He was not yet in

welterweight shape. Mosley looked great physically, but his conditioning needs to match the physique. Once it does, he may be the best welter out there.

…Catch Prince Naseem Hamed on Conan O'Brien lately? Hamed made a typical Hamed-like entrance to his seat. After dancing through the crowd for about 3 minutes to hip-hop music, Hamed finally took his seat next to a shocked Conan. After a one-minute interview about absolutely nothing, Conan told Hamed that he'd run out of time. Show over. An absolute PR disaster for Team Hamed.

…I will continue to repeat this until the bout is over. Holyfield over Lewis in their rematch. No way Holyfield looks this bad in two straight bouts. Lewis will be overconfident, throwing bombs, Holyfield will counter with

lethal combos, and tim-berrrrr!

E-mail me your opinion of the worst strategic moves made in championship boxing history and I'll post them in the next column. Otherwise, send any comments/opinions to leebubba@aol.com. Until next time

WESLEY MOUZON--THE FIGHTER TIME FORGOT

by Arne Steinberg

"Hey, Wesley Mouzon," a voice called out across Frazier's gym in Philadelphia.

I looked around until I thought I had located him standing near me ---- a tall, quiet, well dressed man who carried himself with some dignity.

"Wesley Mouzon?" I said. "How do I know that name?"

"You're too young to know me," he answered abruptly. "I had my last fight in 1946."

"Well, remind me," I said. "Who did you fight?" I knew I had come across the name before, somehow connected with the history of the lightweight division.

Seeing that he couldn't escape easily, he began to name some of his opponents.

"I fought Ike Williams . . .Bob Montgomery . . .Leo Rodak, the featherweight champion . . . Allie Stolz."

Mouzon told me he had been trained by Gene Buffalo, who in turn had been taught by the great Jack Blackburn, trainer of Joe Louis. So I was talking to a link back to the greatest fighters of the early 1900's, since Blackburn, out of Philadelphia, had fought Joe Gans and Sam Langford just after the turn of the century.

Mouzon asked me what was going on earlier near the front of the gym where he had seen me surrounded by a number of long retired Philadelphia fighters who were taking turns illustrating fine points of the game, some of them whacking me around with enthusiasm as they demonstrated.

"They were giving me a beating," I told Mouzon with a laugh.

"You got to be careful,' he said.

My curiosity whetted by our talk, I decided to look up Mouzon's fights the next time I was in a good library. Armed with the dates of his bouts with Ike Williams, Rodak, and Bob Montgomery from their records in the Ring record book, I set out to search through the old newspaper file.

Mouzon's 1945 ten rounder with then NBA lightweight champion Ike Williams ended in a draw. One judge gave the fight to Mouzon, six rounds to four, while the other two scored it a draw by 4-4-2 margins. The write-up said Mouzon was eighteen years old at the time, in his second year as a pro.

I stopped for a moment. Eighteen years old? In 1945? He had told me his last fight was in 1946.

A few fights after the draw with Williams, the eighteen year old whiz scored a clean knockout in six rounds over Leo Rodak. It was the first time in his fourteen year career that the former NBA featherweight champion had been down for the full count of ten. Mouzon was described as " a chocolate blur " in action, with a rapid fire attack capped by a devastating right hand.

Wesley had just turned nineteen four days before he met Bob Montgomery in a non-title bout at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. The threat of rain caused the promoters to rush the main event on earlier than scheduled, and Mouzon scored a stunning second round knockout over the holder of the world lightweight title, New York State version.

"Right hands did it," said a jubilant Mouzon in his dressing room. "I caught him early."

Mouzon's victory earned him a title shot against Montgomery three months later, on November 26, 1946. The nineteen year old challenger was rated an 8-5 favorite to take the title and Mouzon's trainer, Gene Buffalo, agreed with the odds. "No question about it," he said. "New champ tonight. No question."

In an unusual situation created by Mouzon's fast rise to title contention, his co-manager Tom Montgomery was not allowed to work in Mouzon's corner for this fight because of Tom's family relationship with Mouzon's opponent. Tom was Bob Montgomery's brother! When he had originally gotten a piece of young Wes' contract, he had no idea that Mouzon was going to advance so quickly into the title picture.

Mouzon came in at a surprisingly light 132 3/4 on the day of the fight, while Montgomery just made the lightweight limit at 135. Thirteen thousand fans in Philadelphia's Convention Hall watched as Mouzon gave Montgomery a boxing lesson for the first four rounds, working off a beautiful left jab and scoring repeatedly with vicious flurries of punches to the head.

But Montgomery survived the onslaught and in the fifth the tide turned as Bob began to reach his younger opponent with a withering body attack. Soon Mouzon was cut over his left eye, and his nose and mouth bled. He slowed down noticeably, but rallied to fight back fiercely at times.

In the eighth round the end appeared near as a left hook by Montgomery shook Wes badly. At this point Mouzon staged a tremendous rally, throwing everything he had left at Montgomery in one final attempt to turn the tide. He managed to rock Montgomery with a solid right hand, but it was his last gasp. Montgomery withstood the battering and came back to finish Mouzon with four solid shots to the head, knocking the challenger part way through the ropes where he was counted out.

Mouzon cried in the ring when he realized he had lost in his chance at the title.

"Don't think Mouzon isn't a great fighter," the victorious Montgomery said after the fight. "He might be a champion someday."

But the somedays were never to come for nineteen year old Wes. In his dressing room after the fight he complained that he couldn't see out of his right eye. The commission doctor called in an eye specialist who determined that Mouzon had suffered a detached retina during the bout. His career was over at the age of nineteen.

"I had my last fight in 1946," Mouzon had said to me when I first met him. Now I understood why he remembered the year so well.